Belgian Revolution

| Belgian Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Revolutions of 1830 | |||||||

Episode of the Belgian Revolution of 1830, Gustaf Wappers (1834), (Museum of Fine Art, Brussels) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

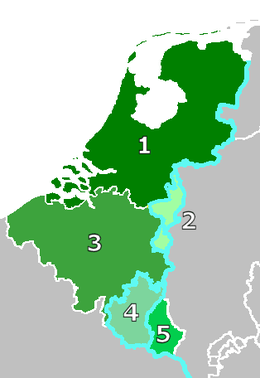

The Belgian Revolution (French: Révolution belge, Dutch: Belgische Revolutie/opstand/omwenteling, German: Belgische Revolution) was the conflict which led to the secession of the southern provinces (mainly the former Southern Netherlands) from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium.

The people of the south were mainly Dutch-speaking Flemings and French-speaking Walloons. Both peoples were traditionally Roman Catholic as contrasted with the Dutch Reformed in the north. Many outspoken liberals regarded King William I's rule as despotic. There were high levels of unemployment and industrial unrest among the working classes.[3]

On 25 August 1830, riots erupted in Brussels and shops were looted. Theatregoers who had just watched the nationalistic opera La muette de Portici joined the mob. Uprisings followed elsewhere in the country. Factories were occupied and machinery destroyed. Order was restored briefly after William committed troops to the Southern Provinces but rioting continued and leadership was taken up by radicals, who started talking of secession.[4]

Dutch units saw the mass desertion of recruits from the southern provinces and pulled out. The States-General in Brussels voted in favour of secession and declared independence. In the aftermath, a National Congress was assembled. King William refrained from future military action and appealed to the Great Powers. The resulting 1830 London Conference of major European powers recognized Belgian independence. Following the installation of Leopold I as "King of the Belgians" in 1831, King William made a belated military attempt to reconquer Belgium and restore his position through a military campaign. This "Ten Days' Campaign" failed because of French military intervention. Not until 1839 did the Dutch accept the decision of the London conference and Belgian independence by signing the Treaty of London.

United Kingdom of the Netherlands

The Dutch overthrew Napoleonic rule in 1813 and, after the British-Dutch Treaty of 1814, named their state the "United Provinces of the Netherlands" or simply the "United Netherlands". After the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the Congress of Vienna created a kingdom for the House of Orange-Nassau, thus combining the United Provinces of the Netherlands with the former Austrian Netherlands in order to create a strong buffer state north of France; with the unification of all the provinces the Netherlands was indeed a rising power. Symptomatic of the tenor of diplomatic bargaining at Vienna was the early proposal to reward Prussia for its staunch fight against Napoleon with the former Habsburg territory. When the British insisted on retaining the former Dutch Ceylon and the Cape Colony (which they had seized while the Netherlands was ruled by Napoleon) the new kingdom of the Netherlands was compensated with these southern provinces (modern Belgium). The union of these two areas reverted to the original cultural area of the Netherlands before the 16th century and were called the "United Kingdom of the Netherlands".

Causes of the Revolution

The Belgian Revolution had many causes and consequences; the main causes were the domination of the Dutch over the economic, political, and social institutions of the Kingdom (although at that time the Belgian population was larger than the Dutch). Catholic bishops in the south viewed the Protestant-majority north with suspicion, and had forbidden working for the new government. This rule, originated in 1815 by Maurice-Jean de Broglie, the French nobleman who was bishop of Ghent, caused an under-representation of Southerners in government apparatus and the army.

The traditional economy of trade and an incipient Industrial Revolution were also centred in the present day Netherlands, particularly in the large port of Amsterdam. Furthermore, although 62% of the population lived in the South, they were assigned the same number of representatives in the States General. At the most basic level, the North was for free trade, while less-developed local industries in the South called for the protection of tariffs. Free trade lowered the price of bread, made from wheat imported through the reviving port of Antwerp; at the same time, these imports from the Baltic depressed agriculture in Southern grain-growing regions.

The more numerous Northern provinces represented a majority in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands' elected Lower Assembly, and therefore the more populous Southerners felt significantly under-represented. King William I was from the North, lived in the present day Netherlands, and largely ignored the demands for greater autonomy. His more progressive and amiable representative living in Brussels, which was the twin capital, was the Crown-Prince William, later King William II, who had some popularity among the upper class but none among peasants and workers.

A linguistic reform in 1823 was intended to make Dutch the official language in the Flemish provinces, since it was the language of most of the Flemish population. This reform met with strong opposition from the upper and middle classes who at the time were mostly French-speaking.[5] On 4 June 1830, this reform was abolished.[6]

Religion was another cause of the Belgian Revolution. In the politics of the south Roman Catholicism was the important factor. Its partisans fought against the freedom of religion proclaimed by William which was at that time still supported by the liberal faction.[7] Over time the (southern) liberal faction began to support the Catholics, partly to accomplish its own goals: freedom of education and freedom of the press.[8]

The Belgian Revolution of 1830 crystallised this antagonism. The language policy of King William was abolished. But no oppression was used. The leading class did not need to be forced to use French.[9]

"Night at the opera"

.jpg)

Catholic partisans watched with excitement the unfolding of the July Revolution in France, details of which were swiftly reported in the newspapers. On 25 August 1830, at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, an uprising followed a special performance, in honor of William I's birthday, of Daniel Auber's La Muette de Portici (The Mute Girl of Portici), a sentimental and patriotic opera set against Masaniello's uprising against the Spanish masters of Naples in the 17th century. After the duet, "Amour sacré de la patrie", (Sacred love of Fatherland) with Adolphe Nourrit in the tenor role, many audience members left the theater and joined the riots which had already begun.[10] The crowd poured into the streets shouting patriotic slogans. The rioters swiftly took possession of government buildings. The following days saw an explosion of the desperate and exasperated proletariat of Brussels, who rallied around the newly created flag of the Brussels independence movement which was fastened to a standard with shoelaces during a street fight and used to lead a counter-charge against the forces of Prince William.

William I sent his two sons, Crown-Prince William and Prince Frederik to quell the riots. William was asked by the Burghers of Brussels to come to the town alone, with no troops, for a meeting; this he did, despite the risks.[11]:390 The affable and moderate Crown Prince William, who represented the monarchy in Brussels, was convinced by the Estates-General on 1 September that the administrative separation of north and south was the only viable solution to the crisis. His father rejected the terms of accommodation that Prince William proposed. King William I attempted to restore the established order by force, but the 8,000 Dutch troops under Prince Frederik were unable to retake Brussels in bloody street fighting (23–26 September).[12] The army was withdrawn to the fortresses of Maastricht, Venlo, and Antwerp, and when the Northern commander of Antwerp bombarded the town, claiming a breach of a ceasefire, the whole of the Southern provinces was incensed. Any opportunity to quell the breach was lost on 26 September when a National Congress was summoned to draw up a Constitution and the Provisional Government was established under Charles Latour Rogier. A Declaration of Independence followed on 4 October 1830.

The European powers and an independent Belgium

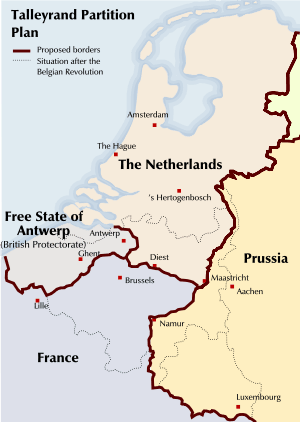

On 20 December 1830 the London Conference of 1830 brought together five major European powers, Austria, Britain, France, Prussia and Russia. At first the European powers were divided over the Belgian cry for independence. The Napoleonic Wars were still fresh in the memories of Europeans, so when the French, under the recently installed July Monarchy, supported Belgian independence, the other powers unsurprisingly supported the continued union of the Provinces of the Netherlands. Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Great Britain all supported the somewhat authoritarian Dutch king, many fearing the French would annex an independent Belgium (particularly the British: see Talleyrand partition plan for Belgium). However, in the end, none of the European powers sent troops to aid the Dutch government, partly because of rebellions within some of their own borders (the Russians were occupied with the November Uprising in Poland and Prussia was saddled with war debt). Britain came to see the benefits of isolating France geographically.

Accession of King Leopold

In November 1830, the National Congress of Belgium was established to create a constitution for the new state. The Congress decided that Belgium would be a popular, constitutional monarchy. On 7 February 1831, the Belgian Constitution was proclaimed. However, no actual monarch yet sat on the throne.

The Congress refused to consider any candidate from the Dutch ruling house of Orange-Nassau.[13] Eventually the Congress drew up a shortlist of three candidates, all of whom were French. This itself led to political opposition, and Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, who had been considered at an early stage but dropped due to French opposition, was proposed again.[14] On 22 April 1831, Leopold was approached by a Belgian delegation at Marlborough House to officially offer him the throne.[15] At first reluctant to accept,[16] he eventually took up the offer, and after an enthusiastic popular welcome on his way to Brussels,[17] Leopold I of Belgium took his oath as king on 21 July 1831.

21 July is generally used to mark the end of the revolution and the start of the Kingdom of Belgium. It is celebrated each year as Belgian National Day.

Post-independence

Ten Days' Campaign

King William was not satisfied with the settlement drawn up in London and did not accept Belgium's claim of independence: it divided his kingdom and drastically affected his Treasury. From 2–12 August 1831 the Dutch army, headed by the Dutch princes, invaded Belgium, in the so-called "Ten Days' Campaign", and defeated a makeshift Belgian force near Hasselt and Leuven. Only the appearance of a French army under Marshal Gérard caused the Dutch to stop their advance. While the victorious initial campaign gave the Dutch an advantageous position in subsequent negotiations, the Dutch were compelled to agree to an indefinite armistice, although they continued to hold Antwerp Citadel and occasionally bombarded the city until French forces forced them out in December 1832. William I would refuse to recognize a Belgian state until April 1839, when he had to yield under pressure by the Treaty of London and reluctantly recognized a border which, with the exception of Limburg and Luxembourg, was basically the border of 1790.

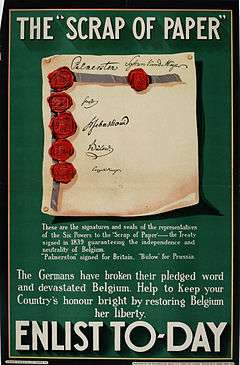

1839 Treaty of London

On 19 April 1839 the Treaty of London signed by the European powers (including the Netherlands) recognized Belgium as an independent and neutral country comprising West Flanders, East Flanders, Brabant, Antwerp, Hainaut, Namur, and Liège, as well as half of Luxembourg and Limburg. The Dutch army, however, held onto Maastricht, and as a result the Netherlands kept the eastern half of Limburg and its large coalfields.[18]

Germany broke the treaty in 1914 when it invaded Belgium, dismissing British protests over a "scrap of paper."[19]

Orangism

As early as 1830 a movement started for the reunification of Belgium and the Netherlands, called Orangism (after the Dutch royal color of orange), which was active in Flanders and Brussels. But industrial cities, like Liège, also had a strong Orangist faction.[20] The movement met with strong disapproval from the authorities. Between 1831 and 1834, 32 incidents of violence against Orangists were mentioned in the press and in 1834 Minister of Justice Lebeau banned expressions of Orangism in the public sphere, enforced with heavy penalties.[21]

175th anniversary commemoration

In 2005, the Belgian revolution of 1830 was depicted in one of the highest value Belgian coins ever minted, the 100 euro "175 Years of Belgium" coin. The obverse depicts a detail from Wappers' painting Scene of the September Days in 1830.

See also

References

- ↑ A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, by Spencer C. Tucker, 2009, p. 1156

- ↑ A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, by Spencer C. Tucker, 2009, p. 1156

- ↑ E.H. Kossmann, The Low Countries 1780-1940 (1978) pp 151-54

- ↑ Paul W. Schroeder, The Transformation of European Politics 1763-1848 (1994) pp 671-91

- ↑ E.H. Kossmann, De lage landen 1780/1980. Deel 1 1780-1914, 1986, Amsterdam, p. 128

- ↑ Jacques Logie, De la régionalisation à l'indépendance, 1830, Duculot, 1980, Paris-Gembloux, p. 21

- ↑ E.H. Kossmann, De lage landen 1780/1980. Deel 1 1780-1914, 1986, Amsterdam, p. 123

- ↑ E.H. Kossmann, De lage landen 1780/1980. Deel 1 1780-1914, 1986, Amsterdam, p. 129

- ↑ E.H. Kossmann, De lage landen 1780/1980. Deel 1 1780-1914, 1986, Amsterdam, p. 148

- ↑ Slatin, Sonia. "Opera and Revolution: La Muette de Portici and the Belgian Revolution of 1830 Revisited", Journal of Musicological Research 3 (1979), 53–54.

- ↑ Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- ↑ Ministerie van Defensie

- ↑ Pirenne 1948, p. 11.

- ↑ Pirenne 1948, p. 12.

- ↑ Pirenne 1948, p. 26.

- ↑ Pirenne 1948, pp. 26-7.

- ↑ Pirenne 1948, p. 29.

- ↑ Schroeder, The Transformation of European Politics 1763-1848 (1994) pp 716-18

- ↑ Larry Zuckerman (2004). The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I. New York University Press. p. 43.

- ↑ Rolf Falter, 1830 De scheiding van Nederland, België en Luxemburg, 2005, Lannoo

- ↑ Universiteit Gent

Bibliography

- Fishman, J. S. "The London Conference of 1830," Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis (1971) 84#3 pp 418–428.

- Fishman, J. S. Diplomacy and Revolution: The London Conference of 1830 and the Belgian Revolt (Amsterdam, 1988)

- Kossmann, E. H. The Low Countries 1780–1940 (1978), pp 151–60

- Kossmann-Putto, J. A. and E. H. Kossmann. The Low Countries: History of the Northern and Southern Netherlands (1987)

- Omond. G. W. T. "The Question of the Netherlands in 1829-1830," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (1919) vol 2 pp. 150–171 in JSTOR

- Pirenne, Henri (1948). Histoire de Belgique (in French). VII: De la Révolution de 1830 à la Guerre de 1914 (2nd ed.). Brussels: Maurice Lamertin.

- Schroeder, Paul W. The Transformation of European Politics 1763-1848 (1994) pp 671–91

- Stallaerts, Robert. The A to Z of Belgium (2010)

- Witte, Els; et al. (2009). Political History of Belgium: From 1830 Onwards. Asp / Vubpress / Upa. pp. 21ff.