Battle of Callinicum

The Battle of Callinicum took place on Easter Saturday, 19 April 531 AD, between the armies of the Byzantine Empire under Belisarius and a Sasanian cavalry force under Azarethes. After a defeat at the Battle of Dara, the Sasanians moved to invade Syria in an attempt to turn the tide of the war. Belisarius' rapid response foiled the plan, and his troops pushed the Persians to the edge of Syria through maneuvering before forcing a battle in which the Sasanians proved to be the pyrrhic victors.

Prelude

In April 531 AD, the Persian king Kavadh I sent an army under spahbod Āzārethes, consisting of a cavalry force numbering about 15,000 Aswaran with an additional group of 5,000 Lakhmid Arab cavalry[3] under Al-Mundhir, to start a campaign, this time not through the heavily fortified frontier cities of Mesopotamia, but through the less conventional but also less defended route in Commagene in order to capture Syrian cities like Antioch.

The Persian army crossed the frontier at Circesium on the Euphrates and marched north. As they neared Callinicum, Belisarius, who commanded the Byzantine army, set out to follow them as they advanced westwards. Belisarius' forces consisted of about 5,000 men and another 3,000 Ghassanid Arab allies, for the remainder of his army had been left to secure Dara. The Byzantines finally blocked the Persian advance at Chalcis, where reinforcements under Hermogenes also arrived, bringing the Byzantine force to some 20,000 men. The Persians were forced to withdraw, and the Byzantines followed them east.

Initially, Belisarius only wanted to drive off the Persians, without a risky battle. The Byzantine troops, however, were restless and anxious, and had become over-confident after their recent victories at Dara and Stala, and clamoured for battle. After failing to convince his men, and realizing they would not fight, and possibly mutiny unless he agreed, Belisarius prepared his force for battle.

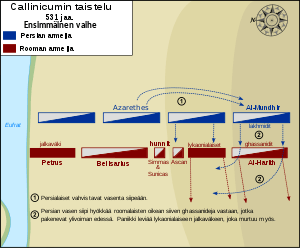

Deployment

The two armies met outside Callinicum on 19 April 531 AD. Both armies formed up differently, Belisarius again choosing an "odd" formation that confused his opposing general. In this case he anchored his left flank on the bank of the river with heavy Byzantine infantry, to their right the army's centre, all of the Byzantine cavalry, many of which were cataphracts under the command of Ascan. Linking the centre to the Byzantine right was a detachment of Lycaonian infantry (under Stephanacius and Longinus), positioned such that their right was anchored on a rising slope occupied by the army's right wing, which consisting of the 5,000 strong Ghassanids allies. Belisarius himself took up position in the centre of his deployment.

Āzārethes, who was an "exceptionally able warrior" according to Byzantine historian and chronicler Procopius, chose a much more conventional deployment by dividing his army into three equal parts with the Lakhmid allies under Al-Mundhir's command constituting the left wing such that they corresponded to the Ghassanid section of the Byzantine army. It is possible that he also held an elite tactical reserve behind his divisions of Persian Savārān.

Battle

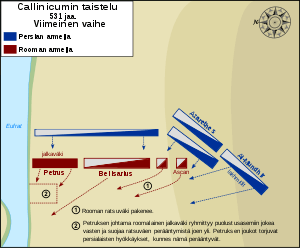

For much of the day, the battle was a stalemate, with the Persian Savārān skirmishing with the Byzantine light and missile troops, with the Persians gaining the upper hand due to a combination of expertise and wind-direction. Meanwhile, however, Āzārethes redeployed some of his cavalry to his left wing. This manoeuvre, which went unnoticed by Belisarius, carried calamitous results for the Byzantines later on. After "two thirds of the day" had elapsed, mostly spent by skirmishing by smaller units, the Persian left came forth and led a devastating and sudden charge in the lead of the Lakhmid contingent under Al-Mundhir. Such was the impact of the charge that the Ghassanids were routed off the field with such ease as to later inspire accusations of treachery. This exposed the right flank of the Lycaonian infantry as well as Ascon's heavy cavalry in the centre.

At this juncture the elite Persian cavalry and their Lakhmid allies were placed upon the rising ground looking down on the unprepared right flank of the Byzantine cavalry of Belisarius' centre. Despite valiant efforts by Ascon to rectify the crisis on his right his cataphracts were crushed, causing the Lycaonian infantry to lose morale and retreat, effectively ridding the Byzantine army of its centre also. With his right flank and centre mauled and driven of the field of battle, Belisarius was forced to retreat in an effort to re-form his line, but the retreat was followed and soon the Byzantines found themselves pressed against the river. Here Belisarius scrambled to form a right angle with whatever remnants and reserves he had left to him in order to brace for the coming onslaught. This proved relatively successful as repeated charges by the Persian cavalry did not result in much more than mounting casualties on both sides. Unfortunately for Belisarius, his men could not hold in such a precarious condition indefinitely.

Zacharias of Mytilene said of the battle: "[The Romans] turned and fled before the Persian attack. Many fell into the Euphrates and were drowned, and others were killed."[4] However, it is unknown what stage of the battle Zachariah was referring to.

According to Malalas, Belisarius fled by boat and let the army to continue the fighting under Sunicas and Simmas.[5] Here on the river, the Byzantines were able to resist the Persians and withdraw much of their army across the river. The Persians attacked the Byzantine lines over the course of several hours, killed many resisting Byzantine troops, and inflicted heavy casualties on them. Eventually, the Byzantines gave up, and Belisarius fled alongside his soldiers.

Aftermath

The strategic outcome of the battle was something of a stalemate; the Byzantine army had lost many soldiers and would not be in fighting condition for months, but the Persians had taken such heavy losses that it was useless as to its original purpose, the invasion of Syria.

Emperor Kavadh I removed General Āzārethes from command and stripped him of his honors, as the casualties were high and the Persian army failed to actually capture any Roman fortress as initially intended.

This mutual disaster was the first of Emperor Justinian's series of (relatively) unsuccessful wars against Sassanids, which led Byzantium to pay heavy tributes in exchange for a peace treaty and the remaining Byzantine land still in Persian hands.

Callinicum ended the first of Belisarius' Persian campaigns, returning all of the land lost to them to Byzantine rule under Justinian I in the Eternal Peace agreement signed in summer 532 AD.

References

- ↑ The Empire at War, A.D. Lee, The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian, ed. Michael Maas, (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 122.

- ↑ Quraysh and the Roman Army: Making Sense of the Meccan Leather Trade, Patricia Crone, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London Vol. 70, No. 1 (2007), 73.

- 1 2 Geoffrey Greatrex and Samuel N.C. Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars Ad 363-628, Part 2, (Routledge, 2002), 92.

- ↑ Historia IX.4,95.4-95.26

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=kiBL4va4B14C&lpg=PA157&pg=PA158

Sources

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002), The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-14687-9

- Martindale, John R.; Jones, A.H.M.; Morris, John (1992), The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire – Volume III, AD 527–641, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-20160-8

- Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the sixth century, Volume 1. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.

- Stanhope, Phillip Henry (1829). The Life of Belisarius. Bradbury and Evans Printers.