Bathurst Correctional Centre

| |

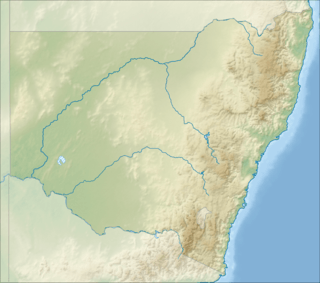

Bathurst Correctional Complex Location in New South Wales | |

| Location | Bathurst, New South Wales, Australia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33°25′04″S 149°33′30″E / 33.41778°S 149.55833°ECoordinates: 33°25′04″S 149°33′30″E / 33.41778°S 149.55833°E |

| Status | Operational |

| Security class | Medium / Minimum |

| Capacity | 222 |

| Opened | 7 June 1888 |

| Former name | Bathurst Gaol |

| Managed by | Corrective Services NSW |

| Website | Bathurst Correctional Centre |

| Building details | |

| General information | |

| Cost | A₤102,000 |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Sandstone and brick |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | |

| Architecture firm | Colonial Architect of New South Wales |

| Official name | Bathurst Correctional Centre |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 00806 |

The Bathurst Correctional Centre, an Australian medium security prison for males, is located in Bathurst, New South Wales, Australia, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) west of the central business district. The facility is operated by Corrective Services NSW, an agency of the Department of Attorney General and Justice, of the Government of New South Wales. The Complex accepts felons charged and convicted under New South Wales and/or Commonwealth legislation and serves as a reception prison for Western New South Wales. A minimum-security cellblock, known as X Wing, is located outside the walls of the main part of the gaol.[1] It also detains males on remand: in 2005, over 20% of Australia's prisoners were on remand.[2]

In 2014 it was reported that between seven and ten female offenders were being housed in the Complex each week.[3]

The current structure incorporates a massive, heritage-listed hand-carved sandstone gate and façade that was opened in 1888 based on designs by the colonial architects, James Barnet and Walter Liberty Vernon.[4][5] The complex came to national prominence during the 1970s due to a series of riots by inmates protesting over living conditions. The complex is listed on the (now defunct) Register of the National Estate and on the New South Wales State Heritage Register since 2 April 1999 as a site of State significance as:[6]

History

Correction facilities were first established in the Bathurst town centre in circa 1830, as the Bathurst Gaol,[7] adjacent to the Bathurst Court House, also designed by Barnet. As sanitary conditions at the town watch house deteriorated, a new gaol was built to Barnet's designs.

The gaol was proclaimed on 7 June 1888, and built at a cost of just over 102,000 pounds. The hand-carved sandstone gate at the new gaol featured an ornate sculptured lion's head holding a key that is a Victorian symbol designed to impress wrongdoers with the immense power and dignity of the law. Legend has it that when the key falls from the lion's mouth, the prisoner are allowed to go free.[5] The new building which contained 308 cells and "commodious workshops" was complete and partly occupied in 1888. This was one of a number of gaols rebuilt or enlarged in this period, the purpose of which was to commence the program of 'restricted association' of prison inmates. The Governor of the Bathurst gaol reported on restricted association as follows:[7][8]

"The restricted treatment for male prisoners has been in vogue for the past seventeen months, and has worked in every way satisfactorily. The prisoners are more obedient, and there is a marked improvement in the discipline; several of them have on many occasions told me that they would not desire to return to the old system. On the 11th December, the new treatment was introduced into the female division, under the supervision of the Comptroller-General for Prisons everything passed off satisfactorily, and ever since has worked well. A few days afterward the whole of the prisoners, by yards (when mustered for dinner) desired me to thank the Comptroller-General for his kindness in placing them under the treatment, stating that they were grateful for the concessions allowed to them in the way of reading and light at night."

Marble cutting and polishing provided works for the prisoners between 1893 and 1925. The gaol accommodated the tougher and more experienced prisoners until 1914 when the gaol then catered for the "previously convicted but hopeful cases". During WW1, rural industries such as dairy, pig-raising, market gardening, hay and fodder production were established. During WW2, the gaol was used as an internment camp for some 200 German and other "enemy aliens". In 1957-62, a new cell block was built outside the gaol's wall with accommodation for 94 prisoners. In 1974, riots at the gaol caused much damage to the main buildings.[8]

The gaol generally accommodated prisoners where they "were deemed amenable to reformative influences" up until 1970 where the gaol was reclassified as a maximum security prison.[7]

Riots

In October 1970, prisoners rebelled as a result of dissatisfaction with their living conditions. As best described by Justice John Nagle during proceedings of the Nagle Royal Commission (1976–1978):[9]

"In common with all maximum security gaols built last century, Bathurst has no glass in the windows. Prisoners, who spent about eighteen hours a day in their cells, frequently had their bedding wet by rain and sleet. There was no heating in the cells despite the extreme cold experienced in Bathurst. The cells could be stifling in summer. Screens were not permitted on the windows, and the piggery operated by the gaol outside its southern wall (between towers 4 and 6) contributed to the flies and insects and all types of odorous smells which invaded the cells in summer."

Prison officials retaliated after the protests by beating and punishing prisoners, in what came to be termed the 'Bathurst Batterings'. The Department of Corrective Services conducted an inquiry. Although the officer who conducted the investigation concluded that a prima facie case existed against prison officers generally at Bathurst, this was not communicated to the Minister. The Department, and the Minister, continued to dismiss allegations of misconduct as unfounded.[9]

Larger riots in February 1974 caused A$10 million in damage, partially due to a fire started by petrol bombs as officials had failed to address earlier prison concerns. Again, referring to Justice Nagle:[9]

"Prison officers were issued with arms, and without having been so ordered, began firing on the prisoners. '.....there was an indiscriminate use of firearms, with no proper instructions given or understanding gained of when or where to use them......' The shootings were, moreover, in direct contravention of instructions sent from departmental headquarters."

As a result of this and problems at other correctional facilities, Justice Nagle was appointed to conduct a Royal Commission to oversee reforms to the Australian penal system.[10]

Further riots arose between 1989 > 1990 when all televisions radios/stereos computers and other electricals, previously allowed and purchased by the inmates through the prison system were now banned by new tougher regulations. the problem arose when said items needed to be confiscated by prison staff, often the same staff who issued the items. The confiscated items were to be kept in the inmates property until release, which became problematic upon release when many inmates need to use public transport in order to return to their place of origin as one cannot carry a television and perhaps a stereo on a bus/train etc.

The riots were the subject of the Cold Chisel song "Four Walls" from the album East.

Name change

Between 1992 and 1993, the name of Bathurst Gaol was changed to Bathurst Correctional Centre.[7]

Description

Bathurst Gaol is composed of a square compound with a gatehouse and two watch towers located at the far corners. The Governor and Deputy Governors Residences are located outside the main compound walls. Internally the (now demolished) chapel formed the focus of the gaol. Four cell ranges and the cookhouse radiated out from the chapel. On one side of the chapel forecourt was the totally separated female compound. On the other side was the male hospital.[8]

Bathurst and Goulburn gaols were almost identical in plan. Goulburn however remains more intact.[8]

Notable prisoners

- Rodney Adler (2005–06) – disgraced Australian businessman and former company director[11]

- Jim McNeil (James Thomas McNeil) (1935-1982), (1973–74) – violent criminal who became better known as the 'prison playwright'

Heritage listing

Bathurst Gaol is significant as one of two model prisons designed by the Colonial Architect's Office in the late 1870s and early 1880s; as an indication of advances in penal architecture in the late nineteenth century; for its continued use as a gaol.[8]

Bathurst Correctional Complex was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[8]

See also

- Stir, 1980 film loosely based on the riots at the prison in 1974

References

- ↑ "Walkabout - Bathurst". Archived from the original on 28 August 2006.

- ↑ Australian Institute of Criminology. "Corrections". www.aic.gov.au/. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Bathurst jail exceeds operating capacity as women are locked in mens prison". Western Advocate. Sovereign Union of First Nations Peoples in Australia. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Bathurst". Historical Towns Directory. Australian Heritage. 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- 1 2 "Bathurst Gaol". The Bathurst Town and around website. Web things. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ "Bathurst Correctional Complex". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bathurst Gaol (1830-1992) / Bathurst Correctional Complex (1992- )". State Records. Government of New South Wales. 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Bathurst Correctional Centre, New South Wales State Heritage Register (NSW SHR) Number H00806". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 Grabosky, P. N. (May 1989). "Wayward governance : illegality and its control in the public sector - Chapter 2: The abuse of prisoners in New South Wales 1943-76". Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. ISBN 0-642-14605-5. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ "Chronology - A History of Australian Prison Reform". Four Corners. Australia: Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 November 2005. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Mitchell, Alex (19 June 2005). "Adler moved to Bathurst prison". The Age. AAP. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

Attribution

![]()

External links

- Bathurst Correctional Centre webpage - part of the Corrective Services NSW