Avalokiteśvara

| Avalokiteśvara | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sanskrit |

अवलोकितेश्वर (IAST: Avalokiteśvara) |

| Chinese |

觀自在菩薩, 觀世音菩薩 or 觀音菩薩(Pinyin: Guānzìzài Púsà, Guānshìyīn Púsà or Guānyīn Púsà) |

| Japanese |

(romaji: Kanjizai Bosatsu, Kanzeon Bosatsu or Kannon Bosatsu) |

| Khmer |

អវលោកិតេស្វរៈ , អវលោកេស្វរៈ , លោកេស្វរៈ (Avalokitesvarak, Avalokesvarak, Lokesvarak) |

| Korean |

관세음보살 (RR: Gwanseeum Bosal) |

| Mongolian |

ᠨᠢᠳᠦ ᠪᠡᠷ ᠦᠵᠡᠭᠴᠢ |

| Thai | พระอวโลกิเตศวรโพธิสัตว์ |

| Vietnamese | Quán Tự Tại Bồ Tát |

| Information | |

| Venerated by | Mahayana, Vajrayana, Theravada*, Taoism, Chinese Folk Religion |

| Attributes | Compassion |

|

| |

Avalokiteśvara or Padmapani (/ˌʌvəloʊkɪˈteɪʃvərə/ UV-əl-oh-kih-TAY-shvər-ə;[1] Sanskrit: अवलोकितेश्वर) is a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. This bodhisattva is variably depicted, described and portrayed in different cultures as either male or female.[2] In Tibet, he is known as Chenrezik, and in Cambodia as អវលោកិតេស្វរៈ.[3] In Chinese Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara has evolved into the somewhat different female figure Guanyin. In Japan this figure is known as Kanzeon or Kannon.

Etymology

The name Avalokiteśvara combines the verbal prefix ava "down", lokita, a past participle of the verb lok "to notice, behold, observe", here used in an active sense; and finally īśvara, "lord", "ruler", "sovereign" or "master". In accordance with sandhi (Sanskrit rules of sound combination), a+īśvara becomes eśvara. Combined, the parts mean "lord who gazes down (at the world)". The word loka ("world") is absent from the name, but the phrase is implied.[4] It does appear in the Cambodian form of the name, Lokesvarak.

The earliest translation of the name into Chinese by authors such as Xuanzang was as Guānzìzài (Chinese: 觀自在), not the form used in East Asian Buddhism today, Guanyin (Chinese: 觀音). It was initially thought that this was due to a lack of fluency, as Guanzizai indicates the original Sanskrit form was Avalokitasvara, "who looks down upon sound" (i.e., the cries of sentient beings who need help).[5] It is now understood that was the original form,[6][7] and is also the origin of Guanyin "Perceiving sound, cries". This translation was favored by the tendency of some Chinese translators, notably Kumārajīva, to use the variant 觀世音 Guānshìyīn "who perceives the world's lamentations"—wherein lok was read as simultaneously meaning both "to look" and "world" (Sanskrit loka; Chinese: 世; pinyin: shì).[5] The original form Avalokitasvara appears in Sanskrit fragments of the fifth century.[8]

This earlier Sanskrit name was supplanted by the form containing the ending -īśvara "lord"; but Avalokiteśvara does not occur in Sanskrit before the seventh century.

The original meaning of the name fits the Buddhist understanding of the role of a bodhisattva. The reinterpretation presenting him as an īśvara shows a strong influence of Hinduism, as the term īśvara was usually connected to the Hindu notion of Vishnu (in Vaishnavism) or Śiva (in Shaivism) as the Supreme Lord, Creator and Ruler of the world. Some attributes of such a god were transmitted to the bodhisattva, but the mainstream of those who venerated Avalokiteśvara upheld the Buddhist rejection of the doctrine of any creator god.[9]

In Sanskrit, Avalokiteśvara is also referred to as Padmapāni ("Holder of the Lotus") or Lokeśvara ("Lord of the World"). In Tibetan, Avalokiteśvara is Chenrézik, (Tibetan: སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ ) and is said to emanate as the Dalai Lama[10] the Karmapa[11][12] and other high lamas. An etymology of the Tibetan name Chenrézik is spyan "eye", ras "continuity" and gzig "to look". This gives the meaning of one who always looks upon all beings (with the eye of compassion).[13]

Origin

Mahayana account

According to the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra, the sun and moon are said to be born from Avalokiteśvara's eyes, Shiva from his brow, Brahma from his shoulders, Narayana from his heart, Sarasvati from his teeth, the winds from his mouth, the earth from his feet, and the sky from his stomach.[14] In this text and others, such as the Longer Sukhavativyuha Sutra, Avalokiteśvara is an attendant of Amitabha.[15]

Some texts which mention Avalokiteśvara include:

- Avataṃsaka Sūtra

- Cundī Dhāraṇī Sūtra

- Eleven-Faced Avalokitesvara Heart Dharani Sutra

- Heart Sutra (Heart Sūtra)

- Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra

- Lotus Sutra

- Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra

- Karuṇāpuṇḍarīka sūtram

- Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī Sutra

- Śūraṅgama Sūtra

The Lotus Sutra is generally accepted to be the earliest literature teaching about the doctrines of Avalokiteśvara.[16] These are found in the Lotus Sutra chapter 25 (Chinese: 觀世音菩薩普門品). This chapter is devoted to Avalokiteśvara, describing him as a compassionate bodhisattva who hears the cries of sentient beings, and who works tirelessly to help those who call upon his name. A total of 33 different manifestations of Avalokiteśvara are described, including female manifestations, all to suit the minds of various beings. The chapter consists of both a prose and a verse section. This earliest source often circulates separately as its own sutra, called the Avalokiteśvara Sūtra (Chinese: 觀世音經; pinyin: Guānshìyīn jīng), and is commonly recited or chanted at Buddhist temples in East Asia.[17]

When the Chinese monk Faxian traveled to Mathura in India around 400 CE, he wrote about monks presenting offerings to Avalokiteśvara.[18] When Xuanzang traveled to India in the 7th century, he provided eyewitness accounts of Avalokiteśvara statues being venerated by devotees from all walks of life: kings, to monks, to laypeople.[18]

.jpg)

In Chinese Buddhism and East Asia, Tangmi practices for the 18-armed form of Avalokiteśvara called Cundī are very popular. These practices have their basis in the early Indian Vajrayana: her origins lie with a yakshini cult in Bengal and Orissa, and her name in Sanskrit "connotes a prostitute or other woman of low caste but specifically denotes a prominent local ogress ... whose divinised form becomes the subject of an important Buddhist cult starting in the eighth century".[19] The popularity of Cundī is attested by the three extant translations of the Cundī Dhāraṇī Sūtra from Sanskrit to Chinese, made from the end of the seventh century to the beginning of the eighth century.[20] In late imperial China, these early esoteric traditions still thrived in Buddhist communities. Robert Gimello has also observed that in these communities, the esoteric practices of Cundī were extremely popular among both the populace and the elite.[21]

In the Tiantai school, six forms of Avalokiteśvara are defined. Each of the bodhisattva's six qualities are said to break the hindrances respectively of the six realms of existence: hell-beings, pretas, animals, humans, asuras, and devas.

Theravāda account

Veneration of Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva has continued to the present day in Sri Lanka:

In times past both Tantrayana and Mahayana have been found in some of the Theravada countries, but today the Buddhism of Ceylon, Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia is almost exclusively Theravada, based on the Pali Canon. The only Mahayana deity that has entered the worship of ordinary Buddhists in Theravada countries is Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. In Ceylon he is known as Natha-deva and mistaken by the majority for the Buddha yet to come, Bodhisattva Maitreya. The figure of Avalokitesvara usually is found in the shrine room near the Buddha image.[22]

In more recent times, some western-educated Theravādins have attempted to identify Nātha with Maitreya Bodhisattva; however, traditions and basic iconography (including an image of Amitābha Buddha on the front of the crown) identify Nātha as Avalokiteśvara.[23] Andrew Skilton writes:[24]

... It is clear from sculptural evidence alone that the Mahāyāna was fairly widespread throughout [Sri Lanka], although the modern account of the history of Buddhism on the island presents an unbroken and pure lineage of Theravāda. (One can only assume that similar trends were transmitted to other parts of Southeast Asia with Sri Lankan ordination lineages.) Relics of an extensive cult of Avalokiteśvara can be seen in the present-day figure of Nātha.

Avalokiteśvara is popularly worshiped in Myanmar, where he is called Lokanat or lokabyuharnat, and Thailand, where he is called Lokesvara. The bodhisattva goes by many other names. In Indochina and Thailand, he is Lokesvara, "The Lord of the World." In Tibet he is Chenrezig, also spelled Spyan-ras gzigs, "With a Pitying Look." In China, the bodhisattva takes a female form and is called Guanyin (also spelled Quanyin, Kwan Yin, Kuanyin or Kwun Yum), "Hearing the Sounds of the World." In Japan, Guanyin is Kannon or Kanzeon; in Korea, Gwan-eum; in Vietnam, Quan Am.[25]

Modern scholarship

Avalokiteśvara is worshipped as Nātha in Sri Lanka. Tamil Buddhist tradition developed in Chola literature, such as in Buddamitra's Virasoliyam , states that the Vedic sage Agastya learnt Tamil from Avalokiteśvara. The earlier Chinese traveler Xuanzang recorded a temple dedicated to Avalokitesvara in the South Indian Mount Potalaka, a Sanskritzation of Pothigai, where Tamil Hindu tradition places Agastya having learnt the Tamil language from Shiva.[26][27][28] Avalokitesvara worship gained popularity with the growth of the Abhayagiri vihāra's Tamraparniyan Mahayana sect.

Western scholars have not reached a consensus on the origin of the reverence for Avalokiteśvara. Some have suggested that Avalokiteśvara, along with many other supernatural beings in Buddhism, was a borrowing or absorption by Mahayana Buddhism of one or more deities from Hinduism, in particular Shiva or Vishnu. This seems to be based on the name Avalokiteśvara.[8]

On the basis of study of Buddhist scriptures, ancient Tamil literary sources, as well as field survey, the Japanese scholar Shu Hikosaka proposes the hypothesis that, the ancient mount Potalaka, the residence of Avalokiteśvara described in the Gaṇḍavyūha Sūtra and Xuanzang’s Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, is the real mountain Pothigai in Ambasamudram, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu.[29] Shu also says that mount Potalaka has been a sacred place for the people of South India from time immemorial. It is the traditional residence of Siddhar Agastya, at Agastya Mala. With the spread of Buddhism in the region beginning at the time of the great king Aśoka in the third century BCE, it became a holy place also for Buddhists, who gradually became dominant as a number of their hermits settled there. The local people, though, mainly remained followers of the Hindu religion. The mixed Hindu-Buddhist cult culminated in the formation of the figure of Avalokiteśvara.[30]

The name Lokeśvara should not be confused with that of Lokeśvararāja, the Buddha under whom Dharmakara became a monk and made forty-eight vows before becoming Amitābha.

Mantras and Dharanis

Mahāyāna Buddhism relates Avalokiteśvara to the six-syllable mantra oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ. In Tibetan Buddhism, due to his association with this mantra, one form of Avalokiteśvara is called Ṣaḍākṣarī "Lord of the Six Syllables" in Sanskrit. Recitation of this mantra while using prayer beads is the most popular religious practice in Tibetan Buddhism.[31] The connection between this famous mantra and Avalokiteśvara is documented for the first time in the Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra. This text is dated to around the late 4th century CE to the early 5th century CE.[32] In this sūtra, a bodhisattva is told by the Buddha that recitation of this mantra while focusing on the sound can lead to the attainment of eight hundred samādhis.[33] The Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra also features the first appearance of the dhāraṇī of Cundī, which occurs at the end of the sūtra text.[20] After the bodhisattva finally attains samādhi with the mantra "oṃ maṇipadme hūṃ", he is able to observe 77 koṭīs of fully enlightened buddhas replying to him in one voice with the Cundī Dhāraṇī: namaḥ saptānāṃ samyaksaṃbuddha koṭīnāṃ tadyathā, oṃ cale cule cunde svāhā.[34]

In Shingon Buddhism, the mantra for Avalokiteśvara is On aruri kya sowa ka (Japanese: おん あるりきゃ そわか)

The Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī is an 82-syllable dhāraṇī for Avalokiteśvara.

Thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara

One prominent Buddhist story tells of Avalokiteśvara vowing never to rest until he had freed all sentient beings from saṃsāra. Despite strenuous effort, he realizes that many unhappy beings were yet to be saved. After struggling to comprehend the needs of so many, his head splits into eleven pieces. Amitābha, seeing his plight, gives him eleven heads with which to hear the cries of the suffering. Upon hearing these cries and comprehending them, Avalokiteśvara tries to reach out to all those who needed aid, but found that his two arms shattered into pieces. Once more, Amitābha comes to his aid and invests him with a thousand arms with which to aid the suffering multitudes.[35]

The Bao'en Temple located in northwestern Sichuan has an outstanding wooden image of the Thousand-Armed Avalokiteśvara, an example of Ming dynasty decorative sculpture.[36][37]

Tibetan Buddhist beliefs

Avalokiteśvara is an important deity in Tibetan Buddhism. He is regarded in the Vajrayana teachings as a Buddha.[38]

In Tibetan Buddhism, Tãrã came into existence from a single tear shed by Avalokiteśvara.[2] When the tear fell to the ground it created a lake, and a lotus opening in the lake revealed Tara. In another version of this story, Tara emerges from the heart of Avalokiteśvara. In either version, it is Avalokiteśvara's outpouring of compassion which manifests Tãrã as a being.[39][40][41]

Manifestations

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Avalokiteśvara has an extraordinarily large number of manifestations in different forms (including wisdom goddesses (vidyaas) directly associated with him in images and texts). Some of the more commonly mentioned forms include:

| Sanskrit | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Āryāvalokiteśvara | Sacred Avalokitesvara | The root form of the Bodhisattva |

| Ekādaśamukha | Eleven Faced | Additional faces to teach all in 10 planes of existence |

| Sahasrabhuja Sahasranetra | Thousand-Armed, Thousand-Eyed Avalokitesvara | Very popular form: sees and helps all |

| Cintamāṇicakra | Wish Fulfilling Avalokitesvara | Holds the bejeweled cintamani wheel |

| Hayagrīva | Horse-necked one | Wrathful form; simultaneously bodhisattva and a Wisdom King |

| Cundī | Extreme purity | Portrayed with many arms |

| Amoghapāśa | Unfailing Rope | Avalokitesvara with rope and net |

| Bhṛkuti | Fierce-Eyed | |

| Pāndaravāsinī | White and Pure | |

| Parnaśabarī | Cloaked With Leaves | |

| Raktaṣadakṣarī | Six Red Syllables | |

| Śvetabhagavatī | White Lord | |

| Udakaśrī | Auspicious Water |

Gallery

Indian cave wall painting of Avalokiteśvara. Ajaṇṭā Caves, 6th century CE.

Indian cave wall painting of Avalokiteśvara. Ajaṇṭā Caves, 6th century CE.

- Torso of Avalokiteśvara from Sanchi in the Victoria and Albert Museum

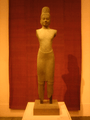

Cambodian statue of Avalokiteśvara. Sandstone, 7th century CE.

Cambodian statue of Avalokiteśvara. Sandstone, 7th century CE. Avalokiteśvara sandstone statue, late 7th century CE.

Avalokiteśvara sandstone statue, late 7th century CE.

Eight-armed Avalokiteśvara, ca. 12th-13th century (Bàyon). The Walters Art Museum.

Eight-armed Avalokiteśvara, ca. 12th-13th century (Bàyon). The Walters Art Museum.- Avalokiteśvara from Bingin Jungut, Musi Rawas, South Sumatra. Srivijayan art (c. 8th-9th century CE)

- The bronze torso statue of Padmapani, 8th century CE Srivijayan art, Chaiya District, Surat Thani Province, Southern Thailand.

.svg.png) The Privy Seal of King Ananda Mahidol of Thailand show a picture of a Bodhisattva, based on a Srivijayan sculpture of Avalokiteśvara Padmapani which was found at Chaiya District, Surat Thani Province.

The Privy Seal of King Ananda Mahidol of Thailand show a picture of a Bodhisattva, based on a Srivijayan sculpture of Avalokiteśvara Padmapani which was found at Chaiya District, Surat Thani Province. Chinese statue of Avalokiteśvara looking out over the sea, c. 1025 CE.

Chinese statue of Avalokiteśvara looking out over the sea, c. 1025 CE.

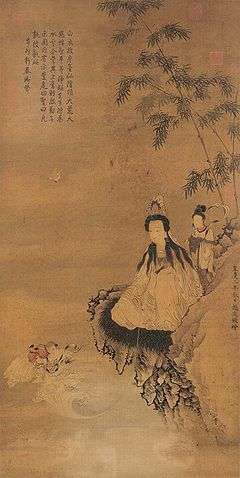

Korean painting of Avalokiteśvara. Kagami Jinjya, Japan, 1310 CE.

Korean painting of Avalokiteśvara. Kagami Jinjya, Japan, 1310 CE. Nepalese statue of Avalokiteśvara with six arms. 14th century CE.

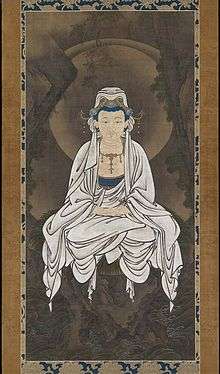

Nepalese statue of Avalokiteśvara with six arms. 14th century CE. Japanese painting of meditating. 16th century CE.

Japanese painting of meditating. 16th century CE. Avalokiteśvara, crimson and gilded wood. Restored in 1656 CE. Bút Tháp Temple, Bắc Ninh Province, Vietnam

Avalokiteśvara, crimson and gilded wood. Restored in 1656 CE. Bút Tháp Temple, Bắc Ninh Province, Vietnam Tibetan statue of Avalokiteśvara with eleven faces.

Tibetan statue of Avalokiteśvara with eleven faces. Malaysia Kek Lok Si Temple in Air Itam, Penang. The world tallest octagonal pavilion to shelter the Goddess of Mercy statue.

Malaysia Kek Lok Si Temple in Air Itam, Penang. The world tallest octagonal pavilion to shelter the Goddess of Mercy statue. Esoteric Cundī form of Avalokiteśvara with eighteen arms.

Esoteric Cundī form of Avalokiteśvara with eighteen arms. Thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara bronze statue from Tibet, circa 1750. Birmingham Museum of Art

Thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara bronze statue from Tibet, circa 1750. Birmingham Museum of Art- Mongolian statue of Avalokiteśvara (Migjid Janraisig). Tallest indoor statue in the world, 26.5-meter-high, 1996 rebuilt, (1913)

Avalokiteśvara in the form of Cintamani Wheel Avalokiteśvara. A dhāraṇī written in Sanskrit in the Siddhaṃ script behind. Singapore.

Avalokiteśvara in the form of Cintamani Wheel Avalokiteśvara. A dhāraṇī written in Sanskrit in the Siddhaṃ script behind. Singapore. Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, Ming Dynasty, Guimet Museum

Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, Ming Dynasty, Guimet Museum Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva in Daan Park, Taipei, Taiwan

Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva in Daan Park, Taipei, Taiwan Statue of Avalokiteśvara, date unknown, bronze and gold

Statue of Avalokiteśvara, date unknown, bronze and gold%2C_the_Museum_of_Vietnamese_History.jpg) Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara from the Museum of Vietnamese History

Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara from the Museum of Vietnamese History

Painting of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva. Sanskrit Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita Sutra manuscript written in the Ranjana script. Nalanda, Bihar, India. Circa 700-1100 CE

Painting of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva. Sanskrit Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita Sutra manuscript written in the Ranjana script. Nalanda, Bihar, India. Circa 700-1100 CE

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Avalokitesvara". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- 1 2 Leighton, Taigen Dan (1998). Bodhisattva Archetypes: Classic Buddhist Guides to Awakening and Their Modern Expression. New York: Penguin Arkana. pp. 158–205. ISBN 0140195564. OCLC 37211178.

- ↑

- ↑ Studholme p. 52-54, 57.

- 1 2 Pine, Red. The Heart Sutra: The Womb of the Buddhas (2004) Shoemaker 7 Hoard. ISBN 1-59376-009-4 pg 44-45

- ↑ Lokesh Chandra (1984). "The Origin of Avalokitesvara" (PDF). Indologica Taurinensia. International Association of Sanskrit Studies. XIII (1985-1986): 189–190. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ↑ Mironov, N. D. (1927). "Buddhist Miscellanea". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2: 241–252. JSTOR 25221116.

- 1 2 Studholme p. 52-57.

- ↑ Studholme p. 30-31, 37-52.

- ↑ "From Birth to Exile". The Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Martin, Michele (2003). "His Holiness the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa". Music in the Sky: The Life, Art, and Teachings of the 17th Karmapa. Karma Triyana Dharmachakra. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑ "Glossary". Dhagpo Kundreul Ling. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Bokar Rinpoche (1991). Chenrezig Lord of Love - Principles and Methods of Deity Meditation. San Francisco, California: Clearpoint Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-9630371-0-2.

- ↑ Studholme, Alexander (2002). The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum: A Study of the Karandavyuha Sutra. State University of New York Press. pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Studholme, Alexander (2002). The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum: A Study of the Karandavyuha Sutra. State University of New York Press. pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Huntington, John (2003). The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art: p. 188

- ↑ Baroni, Helen (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism: p. 15

- 1 2 Ko Kok Kiang. Guan Yin: Goddess of Compassion. 2004. p. 10

- ↑ Lopez 2013, p. 204.

- 1 2 Studholme, Alexander (2002). The Origins of Oṃ Maṇipadme Hūṃ: A Study of the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra: p. 175

- ↑ Jiang, Wu (2008). Enlightenment in Dispute: The Reinvention of Chan Buddhism in Seventeenth-Century China: p. 146

- ↑ Baruah, Bibhuti. Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism. 2008. p. 137

- ↑ "Art & Archaeology - Sri Lanka - Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara".

- ↑ Skilton, Andrew. A Concise History of Buddhism. 2004. p. 151

- ↑ https://www.thoughtco.com/avalokiteshvara-bodhisattva-450135

- ↑ Iravatham Mahadevan (2003), EARLY TAMIL EPIGRAPHY, Volume 62. pp. 169

- ↑ Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta Sastri (1963) Development of Religion in South India - Page 15

- ↑ Layne Ross Little (2006) Bowl Full of Sky: Story-making and the Many Lives of the Siddha Bhōgar, pp. 28

- ↑ Hirosaka, Shu. The Potiyil Mountain in Tamil Nadu and the origin of the Avalokiteśvara cult

- ↑ Läänemets, Märt (2006). "Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara in the Gandavyuha Sutra". Chung-Hwa Buddhist Studies 10, 295-339. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ↑ Studholme, Alexander (2002). The Origins of Oṃ Maṇipadme Hūṃ: A Study of the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra: p. 2

- ↑ Studholme, Alexander (2002) The Origins of Oṃ Maṇipadme Hūṃ: A Study of the Kāraṇḍavyūha sūtra: p. 17

- ↑ Studholme, Alexander (2002). The Origins of Oṃ Maṇipadme Hūṃ: A Study of the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra: p. 106

- ↑ "Saptakoṭibuddhamātṛ Cundī Dhāraṇī Sūtra". Lapis Lazuli Texts. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ Venerable Shangpa Rinpoche. "Arya Avalokitesvara and the Six Syllable Mantra". Dhagpo Kagyu Ling. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Guxi, Pan (2002). Chinese Architecture -- The Yuan and Ming Dynasties (English ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 245&ndash, 246. ISBN 0-300-09559-7.

- ↑ Bao Ern Temple, Pingwu, Sichuan Province Archived 2012-10-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Еше-Лодой Рипоче. Краткое объяснение сущности Ламрима. Спб.-Улан-Удэ, 2002. С. 19 (in Russian)

- ↑ Dampa Sonam Gyaltsen (1996). The Clear Mirror: A Traditional Account of Tibet's Golden Age. Shambhala. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-55939-932-6.

- ↑ Shaw, Miranda (2006). Buddhist Goddesses of India. Princeton University Press. p. 307. ISBN 0-691-12758-1.

- ↑ Bokar Tulku Rinpoche (1991). Chenrezig, Lord of Love: Principles and Methods of Deity Meditation. ClearPoint Press. ISBN 978-0-9630371-0-7.

References

- Buswell, Robert; Lopez, Donald S. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- Ducor, Jérôme (2010). Le regard de Kannon (in French). Gollion: Infolio éditions / Genève: Musée d'ethnographie de Genève. p. 104. ISBN 978-2-88474-187-3. ill. colour

- Getty, Alice (1914). The gods of northern Buddhism: their history, iconography and progressive evolution through the northern Buddhist countries. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Holt, John (1991). Buddha in the Crown: Avalokitesvara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195064186.

- McDermott, James P. (1999). "Buddha in the Crown: Avalokitesvara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (1): 195–196.

- Studholme, Alexander (2002). The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum. Albany NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-5389-8.

- Tsugunari, Kubo; Akira (tr.), Yuyama (2007). The Lotus Sutra (PDF) (Revised 2nd ed.). Berkeley, Calif.: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 978-1-886439-39-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-02.

- Yü, Chün-fang (2001). Kuan-Yin: The Chinese Transformation of Avalokitesvara. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12029-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Avalokiteshvara. |

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Yoga oracle#81 The Blessing of the Karmapa (meditating on a Thanka of Avalokitesvara) |

- The Origin of Avalokiteshvara of Potala

- An Explanation of the Name Avalokiteshvara

- The Bodhisattva of Compassion and Spiritual Emanation of Amitabha - from Buddhanature.com

- Depictions at the Bayon in Cambodia of Avalokiteshvara as the Khmer King Jayavarman VII

- Mantra Avalokitesvara

- Avalokiteshvara at Brittanica.com

- Chenrezig Tibetan Buddhist Center of Philadelphia