Auditing (Scientology)

In the Church of Scientology, auditing is a process wherein the auditor takes an individual, known as a "preclear", through times in their life and gets rid of any hold negative situations have on them. Auditing began as an integral part of the Dianetics movement and has since, with the E-meter, become a core practice in Scientology. Auditing is defined by the Church as "the application of Dianetics or Scientology processes and procedures to someone by a trained auditor. One formal definition of auditing is the action of asking a person a question (which he can understand and answer), getting an answer to that question and acknowledging him or her for that answer."[1] Auditing is considered "a technical measure," that according to the Church, "lifts the burdened individual, the 'preclear,' from a level of spiritual distress to a level of insight and inner self-realization." The process is meant to bring the individual to clear status.

According to scholar Eric Roux, auditing is one of the "core practices" of Scientology. The primary aim of auditing in Scientology doctrine is to rediscover an individual's natural abilities, while understanding that one is a spiritual being.

Some auditing actions use commands, for example "Recall a time you knew you understood someone," and some auditing actions use questions such as, "What are you willing for me to talk to others about?"[2]

Description

In the context of Dianetics or Scientology, auditing is an activity where an auditor, trained in the task of communication, listens and gives auditing commands to a subject, who is referred to as a "preclear", or more often as a "pc". While auditing sessions are confidential, the notes taken by the auditor during auditing sessions. Preclears never see their own pc folders.Scientology does not agree with evaluation of a PC. Having a pc observe their own folder might bring an evaluation into his/her universe making it harder for him/her to spot the actual core of a current situation.

Auditing involves the use of "processes," which are sets of questions asked or directions given by an auditor. When the specific objective of any one process is achieved, the process is ended and another can then be started. Through auditing, the subjects are said to free themselves from barriers that inhibit their natural abilities. Outlining the auditing process, Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard explained:

Charge is that which prevents the pc from thinking on a subject. Prevents him from thinking on a subject or getting rid of a subject or approaching a subject. Sum it up to handling a subject. Charged.[3]

Scientologists the person being audited is completely aware of everything that happens and becomes even more alert as auditing progresses. As Hubbard wrote,

One of the great truths of Scientology is that INCREASED AWARENESS IS THE ONLY FACTOR WHICH OFFERS ANY ROAD OUT.[4]

The auditor is obliged by the Church's doctrine to maintain a strict code of conduct, called the Auditor's Code.[5] Auditing is said to be successful only when the auditor conducts himself in accordance with the Code.[6] A violation of the Auditor's Code is considered a high crime under Scientology policy.

The code outlines a series of 29 promises, which include pledges such as:[7]

- Not to evaluate for the preclear or tell him what he should think about his case in session

- Not to invalidate the preclear's case or gains in or out of session

- Never to use the secrets of a preclear divulged in session for punishment or personal gain

The main intention of an auditing session is to remove "charted incidents" that have caused trauma, which are believed in Scientology to be stored in the reactive mind. These incidents must then be eliminated for proper functioning, in accordance with the Church's belief.[8]

According to the religion researcher Hugh B. Urban, both current Scientologists and people who have become disaffected with Scientology generally agree that auditing can trigger personal insights and cause dramatic changes in one's psychological state.[9] The recalling and expression of old hurts in response to the auditor's questions may feel like an unburdening, followed by a period of elation, as though a weight has been lifted off the practitioner's shoulders.[9]

Scientology makes a distinction between auditors, those who practice auditing, and publics, those who receive the prosses but do not receive training to perform the practice on others until they wish to do so. Auditors are deemed in Scientology as higher state individuals as they are regarded as more focused in achieving the goals of the religion, or "clearing the planet," in Scientological terminology.[10]

In 1952, auditing techniques "began to focus on the goal of exteriorizing the thetan" in order to provide one with a complete awareness of one's spiritual nature. According to Eric Roux, "many auditing techniques were designed towards gaining spiritual freedom by way of increasing communication of the thetan with the physical universe, in order to develop freedom from the physical universe." Scientologists believe that the thetan "can exist separately from the body, with a full awareness of being out of it, a phenomenon which Scientologists call 'exteriorization.' (Hubbard 1952)[11]

E-meter

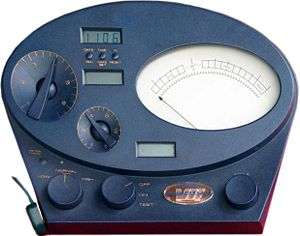

Most auditing sessions employ a device called the Hubbard Electropsychometer or E-meter. This device is a custom electrodermal activity measurement device. It measures changes in the electrical resistance of the preclear by passing a small electric current (typically in the range from 50 µA to 120 µA) through the preclear's body by means of a pair of tin-plated tubes originally much like empty soup cans, attached to the meter by wires and held by the preclear during auditing. These changes in electrical resistance are believed by Scientologists to be a reliable and a precise indication of changes in the reactive mind of the preclear.

According to Scientologist doctrine, the development of the E-meter enabled auditing techniques and made it more precise. Later, the E-meter was used to identify which processes should (and could) be run[12] and equally crucially, to determine when to stop running a particular action. As a repair tool, the E-meter reacts to a list of possible difficulties and relevant phrases called out by the auditor, helping to guide the auditor to the difficulty.[13] Hubbard clarified how the E-Meter should be used in conjunction with auditing:

HCO Bulletin 3 December 1978

One of the governing laws of auditing is that you don't run unreading items. It doesn't matter what you are auditing. You don't run unreading items. And you don't run unreading flows. You don't run an unreading anything. Ever. For any reason.

Auditing is aimed at reactivity. You run what reacts on the meter because it reacts and is therefore part of the reactive mind. A read means there is charge present and available to run. Running reading items, flows and questions is the only way to make a pc better. This is our purpose in auditing.

- L Ron Hubbard

Hubbard claimed that the device also has such sensitivity that it can measure whether or not fruits can experience pain, claiming in 1968 that tomatoes "scream when sliced."[14][15][16]

Scientology teaches that individuals are immortal souls or spirits (called thetans by Scientology) and are not limited to a single lifetime. The E-meter is believed to aid the auditor in locating subliminal memories ("engrams", "incidents", and "implants") of past events in a thetan's current life and in previous ones. In such Scientology publications as Have You Lived Before This Life, Hubbard wrote about past life experiences dating back billions and even trillions of years.[17]

When various foundations of Dianetics were formed in the 1950s, auditing sessions were a hybrid of confession, counseling and psychotherapy. According to Passas and Castillo, the e-meter was believed to be used to "disclose truth to the individual who is being processed and thus free him spiritually."[18]

Bridge

Back in 1950, at the very end of his book, Dianetics: the Modern Science of Mental Health, Hubbard talks about a bridge from one plateau of existence to another, higher plateau.

Hubbard wanted to make the processes structured in such a way that one could take a new person and walk them through standardized steps, one after another, to cross this hypothesized "Bridge". This intent led to the development of the Standard Operating Procedure for Theta Clearing by 1952.[19] Standard Operating Procedure for the Church of Scientology changed rapidly, meaning that when somebody was trained as an auditor they were almost immediately out of date with the latest procedures.

In 1970, the Standard Operating Procedure was used to create the Classification and Gradation Chart. This chart, first published in 1965 and revised in 1966, 1968 and 1969, had the steps of the bridge plotted out from a beginner at the bottom to the highest states attainable at the top.[20] The left-hand side of the chart contains auditor skill levels, while the right-hand side contains pre-clear grades and OT (Operating Thetan) levels.

The 1970 version of the chart is entitled "Classification Gradation and Awareness Chart of Levels and Certificates". By 1974 the above title had slipped down a little to make way for "THE BRIDGE" as the top line, with "TO A NEW WORLD" underneath in a smaller font. A more recent (circa 2016) chart is entitled "THE BRIDGE TO TOTAL FREEDOM" and subtitled "SCIENTOLOGY CLASSIFICATION GRADATION AND AWARENESS CHART."[21]

Procedure

Each Grade on the Bridge has a list of processes that auditors should run. Below are sample commands from processes run in each Grade.

- ARC Straightwire: "Recall a communication." [22]

- Grade 0: "Recall a place from which you have communicated to another." [23]

- Grade I: "Recall a problem you have had with another." [24]

- Grade II: "Recall a secret." [25]

- Grade III: "Can you recall a time of change?" [26]

- Grade IV: "What about a victim could you be responsible for?" [27]

Each Grade is targeted at a specific area of potential difficulty a person might have. The working hypothesis is that if the subject matter is not "charged"; in other words, if it is not causing any difficulty, then it will not read on the E-meter, and therefore will not be run.

The above processes demonstrate a key aspect of Scientology processes. The question or command can be quite general. It is absolutely forbidden (by the Auditor's Code) for the auditor to interpret the preclear's answer or discuss it in any way.

A possible audit could be performed like this:

- Auditor: "Recall a secret."

- Preclear: "I deliberately broke the window in the hall with my ball."

- Auditor: "Thank you. . Recall a secret."

- Preclear: "I saw my sister kissing the postman."

- Auditor: "Ok. . Recall a secret."

- Preclear: "I hate my mum's apple pie, but my dad told me not to tell her."

- Auditor: "Thank you. Recall a secret."

Controversy

Preclear folders

The Scientology and Dianetics auditing process has raised concerns from a number of quarters, as auditing sessions are permanently recorded in the form of handwritten notes in preclear folders, which are supposed to be kept private. Judge Paul Breckenridge, in Church of Scientology of California vs. Gerald Armstrong, noted that Mary Sue Hubbard (the plaintiff in that case) "authored the infamous order 'GO 121669', which directed culling of supposedly confidential P.C. [Preclear] files/folders for the purposes of internal security". This directive was later canceled because it was not part of Scientology as written by L. Ron Hubbard. Bruce Hines has noted in an interview with Hoda Kotb that Scientology's collecting of personal and private information through auditing can possibly leave an adherent vulnerable to potential "blackmail" should they ever consider disaffecting from the church.[28] A number of sources have claimed that preclear folders have indeed been used for intimidation and harassment.[29][30][31][32]

Anderson Report

In 1965 the Anderson Report, an official inquiry conducted for the state of Victoria, Australia, found that auditing involved a form of "authoritative" or "command" hypnosis, in which the hypnotist assumes "positive authoritative control" over the subject. "It is the firm conclusion of this Board that most scientology and dianetic techniques are those of authoritative hypnosis and as such are dangerous. ... the scientific evidence which the Board heard from several expert witnesses of the highest repute ... which was virtually unchallenged - leads to the inescapable conclusion that it is only in name that there is any difference between authoritative hypnosis and most of the techniques of scientology. "[33]

As a result of the Anderson Report, a number of restrictive laws were passed in Australia against Scientology, but in the ensuing years, all were repealed. As of 2011 auditing is considered a spiritual practice by the government of Australia.

Claims

L. Ron Hubbard claimed benefits from auditing including improved IQ, improved ability to communicate, enhanced memory and alleviation of issues such as psychosis, dyslexia and attention deficit disorder.[34][35] Some people have alleged that auditing amounts to medical treatment without a license, and in the 1950s, some auditors were arrested on the charge.[36] The Church disputes that it is practicing medicine, and it has successfully established in United States courts of law that auditing addresses only spiritual relief.[37] According to the Church, the psychotherapist treats mental health and the Church treats the spiritual being. Hubbard clarified the difference between the two:

If we processed a specific type of aberration, we of course would be in the field of mental healing, and so forth. But long ago we actually discovered that we must not process specific aberrations, which takes us out of the field of mental healing.

It is quite fatal to do this because in the first place it's an evaluation for the case. In the second place, it's a negative type process; you're condemning the individual for hitting girls. Doesn't validate the individual at all. Do you follow? And if carried on very long, does not result in the betterment of an individual. All we're interested in is the spiritual betterment of the individual ...[38]

In 1971, a ruling of the United States District Court, District of Columbia (333 F. Supp. 357), specifically stated that the E-meter "has no proven usefulness in the diagnosis, treatment or prevention of any disease, nor is it medically or scientifically capable of improving any bodily function."[39] As a result of this ruling, Scientology now publishes disclaimers in its books and publications declaring that the E-meter "by itself does nothing" and that it is used specifically for spiritual purposes.[39]

Child auditors

Dutch investigative reporter Rinke Verkerk reported that she was given an auditing session by an 11-year-old in the Netherlands.[40] This has been criticized by clinical psychologists and child psychologists, on the grounds that secondary stress can affect children more strongly than adults.[41] The fact that the child was working full days for a whole weekend was also considered to be problematic.[41]

Notes

Note: HCOB refers to "Hubbard Communications Office Bulletins", HCOPL refers to "Hubbard Communications Office Policy Letters", and SHSBC refers to "Saint Hill Special Briefing Courses". All have been made publicly available by the Church of Scientology in the past, both as individual documents or in bound volumes.

- ↑ "Scientology glossary". Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Mini List of Grade 0-IV Processes". HCO Bulletin 8 September 1978RB.

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron (8 Feb 1962). "3DXX Assessment". Tape 6202C08. SHSBC 109.

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron (1 Sep 1957). "The Big Auditing Problem". Professional Auditor's Bulletin. PAB 119.

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron (29 October 1954). "The Auditor's Code 1954". Professional Auditor's Bulletin (PAB 38).

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Questionable Auditing". HCO Bulletin 11 July 1982, Iss II.

- ↑ website: Scientology.org / THE AUDITOR'S CODE

- ↑ Rothstein, Mikael (2016). "The Significance of Rituals in Scientology: A Brief Overview and a Few Examples". Numen. 63 (1): 54–70. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- 1 2 Urban (2011), p. 47

- ↑ Lewis, James R. (2009). Scientology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-533149-4.

- ↑ Roux, Eric (2018). "Scientology auditing: Pastoral counselling or a religious path to total spiritual freedom". In Harvey, Sarah; Stedinger, Silke; Beckford, James A. New Religious Movements and Counselling: Academic, Professional and Personal Perspectives. Routledge. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Unreading Questions and Items". HCO Bulletin 27 May 1970. VII.

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Auditing by Lists Revised". HCO Bulletin 3 July 1971. VII.

- ↑ "30 Dumb Inventions". Life. 1968-01-01. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ "Scientology Mythbusting with Jon Atack: The Tomato Photo!". tonyortega.org. 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- ↑ Cooper, Paulette (1971). "Chapter 18: The E-Meter". The Scandal of Scientology. Belmont/Tower; Mass market edition.

- ↑ Lewis, James R. (2009). Scientology. Oxford University Press.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Passas, Nikos; Castillo, Manuel Escamilla (1992). "Scientology and its 'clear' business". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 10 (1): 103–116. doi:10.1002/bsl.2370100110.

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron (Nov 1952). "Procedures for Theta Clearing". Journal of Scientology (6-G).

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Programming of Cases". HCO Bulletin 12 June 1970. C/S series 2.

- ↑ "What is the Bridge in Scientology". Scientology. Church of Scientology International. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Expanded ARC Straightwire Grade Process Checklist". HCO Bulletin 14 Nov 1987 (I).

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Expanded Grade 0 Process Checklist". HCO Bulletin 14 Nov 1987 (II).

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Expanded Grade I Process Checklist". HCO Bulletin 14 Nov 1987 (III).

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Expanded Grade II Process Checklist". HCO Bulletin 14 Nov 1987 (IV).

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Expanded Grade III Process Checklist". HCO Bulletin 14 Nov 1987 (V).

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron. "Expanded Grade IV Process Checklist". HCO Bulletin 14 Nov 1987 (VI).

- ↑ Hines, Bruce. "Inside Scientology". Countdown with Keith Olbermann (Interview). Interviewed by Hoda Kotb. CNBC.

- ↑ Atack, Jon (1990). "Chapter Four - The Clearwater Hearings". A Piece of Blue Sky. Lyle Stuart. p. 448. ISBN 0-8184-0499-X.

- ↑ Girardi, Steven (1982-05-09). "Witnesses Tell of Break-ins, Conspiracy". Clearwater Sun. pp. 1A.

Commissioners heard also from a former Guardian Office worker who said she used the sect's "confessional files" during several campaigns to discredit defected Scientologists

- ↑ Barnes, John (1984-10-28). "Sinking the Master Mariner". Sunday Times Magazine.

- ↑ Wakefield, Margery (2009). The road to Xenu : life inside Scientology. Raleigh, N.C.: Lulu. p. 188. ISBN 9780557090402. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ Report of the Board of Enquiry into Scientology) by Kevin Victor Anderson, Q.C. Published 1965 by the State of Victoria, Australia.

- ↑ "The Original Scientology Exposé". The Saturday Evening Post. February 8, 2011. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ↑ "Have You Ever Been a Boo-Hoo?" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ↑ Urban, Hugh B. (2011-08-22). The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion. Princeton University Press. p. 62. ISBN 069114608X.

- ↑ Wright, Skelley (February 5, 1969). "Opinion". Washington, DC: United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. p. 1154. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ Hubbard, L Ron (6 Dec 1966). "Scientology Definitions II". Tape 6612C06. SHSBC 83(446).

- 1 2 http://www-2.cs.cmu.edu/~dst/Secrets/E-Meter/Mark-VII/

- ↑ Verkerk, Rinke (20 May 2015). "Vier maanden undercover bij de Scientologykerk - Media - Voor nieuws, achtergronden en columns". De Volkskrant (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- 1 2 Kuiper, Rik (19 May 2015). "Scientologykerk laat kinderen therapieën volwassenen leiden - Binnenland - Voor nieuws, achtergronden en columns". De Volkskrant (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 January 2017.

References

- Urban, Hugh B. (2011), The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion, Princeton Press, ISBN 0-691-14608-X

External links

- Church of Scientology official website

- Secrets of Scientology: The E-Meter

- Free Zone E-Meters at Curlie (based on DMOZ)