Ashoka

| Ashoka | |

|---|---|

| Chakravartin[1][2] | |

| |

| 3rd Mauryan emperor | |

| Reign | c. 268 – c. 232 BCE[5] |

| Coronation | 268 BCE[5] |

| Predecessor | Bindusara |

| Successor | Dasharatha |

| Born | Pataliputra, modern-day Patna, Bihar, India |

| Died |

232 BCE Pataliputra, modern-day Patna, Bihar, India |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Maurya |

| Father | Bindusara |

| Mother | Subhadrangi (also called Dharma) |

| Maurya Empire (322 BCE–180 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

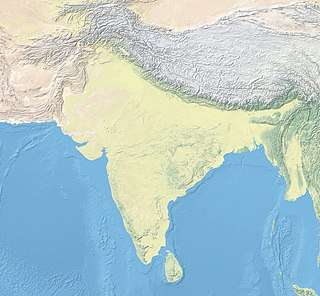

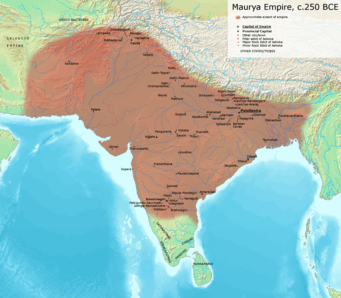

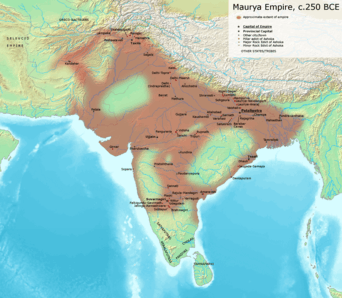

Ashoka (English: /əˈʃoʊkə/; Sanskritized as IAST: Aśoka), or in contemporary Prakrit Asoka (𑀅𑀲𑁄𑀓),[6] sometimes Ashoka the Great, was an Indian emperor of the Maurya Dynasty, who ruled almost all of the Indian subcontinent from c. 268 to 232 BCE.[7][8] The grandson of the founder of the Maurya Dynasty, Chandragupta Maurya, Ashoka promoted the spread of Buddhism. One of India's greatest emperors, Ashoka expanded Chandragupta's empire to reign over a realm stretching from present-day Afghanistan in the west to Bangladesh in the east. It covered the entire Indian subcontinent except for parts of present-day Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala. The empire's capital was Pataliputra (in Magadha, present-day Patna), with provincial capitals at Taxila and Ujjain.

Ashoka waged a destructive war against the state of Kalinga (modern Odisha),[9] which he conquered in about 260 BCE.[10] In about 263 BCE, he converted to Buddhism[9] after witnessing the mass deaths of the Kalinga War, which he had waged out of a desire for conquest and which reportedly directly resulted in more than 100,000 deaths and 150,000 deportations.[11] He is remembered for the Ashoka pillars and edicts, for sending Buddhist monks to Sri Lanka and Central Asia, and for establishing monuments marking several significant sites in the life of Gautama Buddha.[12]

Beyond the Edicts of Ashoka, biographical information about him relies on legends written centuries later, such as the 2nd-century CE Ashokavadana ("Narrative of Ashoka", a part of the Divyavadana), and in the Sri Lankan text Mahavamsa ("Great Chronicle"). The emblem of the modern Republic of India is an adaptation of the Lion Capital of Ashoka. His Sanskrit name "Aśoka" means "painless, without sorrow" (the a privativum and śoka, "pain, distress"). In his edicts, he is referred to as Devānāmpriya (Pali Devānaṃpiya or "the Beloved of the Gods"), and Priyadarśin (Pali Piyadasī or "He who regards everyone with affection"). His fondness for his name's connection to the Saraca asoca tree, or "Ashoka tree", is also referenced in the Ashokavadana. In The Outline of History, H.G. Wells wrote, "Amidst the tens of thousands of names of monarchs that crowd the columns of history, their majesties and graciousnesses and serenities and royal highnesses and the like, the name of Ashoka shines, and shines, almost alone, a star."[13]

Biography

Ashoka's early life

Ashoka was born to the Mauryan emperor, Bindusara and Subhadrangī (or Dharmā).[14] He was the grandson of Chandragupta Maurya, founder of the Maurya dynasty, who was born in a humble family, and with the counsel of Chanakya ultimately built one of the largest empires in ancient India.[15][16][17] According to Roman historian Appian, Chandragupta had made a "marital alliance" with Seleucus; there is thus a possibility that Ashoka had a Seleucid Greek grandmother.[18][19] An Indian Puranic source, the Pratisarga Parva of the Bhavishya Purana, also described the marriage of Chandragupta with a Greek ("Yavana") princess, daughter of Seleucus.[20][21]

The ancient Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain texts provide varying biographical accounts. The Avadana texts mention that his mother was queen Subhadrangī. According to the Ashokavadana, she was the daughter of a Brahmin from the city of Champa.[22][23]:205 She gave him the name Ashoka, meaning "one without sorrow". The Divyāvadāna tells a similar story, but gives the name of the queen as Janapadakalyānī.[24][25] Ashoka had several elder siblings, all of whom were his half-brothers from the other wives of his father Bindusara. Ashoka was given royal military training.[26]

Rise to power

The Buddhist text Divyavadana describes Ashoka putting down a revolt due to activities of wicked ministers. This may have been an incident in Bindusara's times. Taranatha's account states that Chanakya, Bindusara's chief advisor, destroyed the nobles and kings of 16 towns and made himself the master of all territory between the eastern and the western seas. Some historians consider this as an indication of Bindusara's conquest of the Deccan while others consider it as suppression of a revolt.[22]

- Governor of Ujain

Following this, Ashoka was stationed at Ujain, the capital of Malwa, as governor.[22] A commemorative inscription found in Saru Maru, Madhya Pradesh, mentions the visit of Piyadasi (honorific name used by Ashoka in his inscriptions) as he was still an unmarried Prince.[27][28] This inscription confirms Ashoka's presence in Madhya Pradesh as a young man, and his status while he was there.[29]

Piyadasi nama/ rajakumala va/ samvasamane/ imam desam papunitha/ viahara(ya)tay(e).

The king, who (now after consecration) is called "Piyadasi", (once) came to this place for a pleasure tour while still a (ruling) prince, living together with his unwedded consort.

— Commemorative Inscription of the visit of Ashoka, Saru Maru. Translated by Falk.[29]

Bindusara's death in 272 BCE led to a war over succession. According to the Divyavadana, Bindusara wanted his elder son Susima to succeed him but Ashoka was supported by his father's ministers, who found Susima to be arrogant and disrespectful towards them.[30] A minister named Radhagupta seems to have played an important role in Ashoka's rise to the throne. The Ashokavadana recounts Radhagupta's offering of an old royal elephant to Ashoka for him to ride to the Garden of the Gold Pavilion where King Bindusara would determine his successor. Ashoka later got rid of the legitimate heir to the throne by tricking him into entering a pit filled with live coals. Radhagupta, according to the Ashokavadana, would later be appointed prime minister by Ashoka once he had gained the throne. The Dipavansa and Mahavansa refer to Ashoka's killing 99 of his brothers, sparing only one, named Vitashoka or Tissa,[5] although there is no clear proof about this incident (many such accounts are saturated with mythological elements). The coronation happened in 269 BCE, four years after his succession to the throne.[31]

Buddhist legends state that Ashoka was bad-tempered and of a wicked nature. He built Ashoka's Hell, an elaborate torture chamber described as a "Paradisal Hell" due to the contrast between its beautiful exterior and the acts carried out within by his appointed executioner, Girikaa.[33] This earned him the name of Chanda Ashoka (Caṇḍa Aśoka) meaning "Ashoka the Fierce" in Sanskrit. Professor Charles Drekmeier cautions that the Buddhist legends tend to dramatise the change that Buddhism brought in him, and therefore, exaggerate Ashoka's past wickedness and his piousness after the conversion.[34]

Ascending the throne, Ashoka expanded his empire over the next eight years, from the present-day Assam in the East to Balochistan in the West; from the Pamir Knot in Afghanistan in the north to the peninsula of southern India except for present day Tamil Nadu and Kerala which were ruled by the three ancient Tamil kingdoms.[25][35]

Marriage

From the various sources that speak of his life, Ashoka is believed to have had five wives. They were named Devi (or Vedisa-Mahadevi-Shakyakumari), the second queen, Karuvaki, Asandhimitra (designated agramahisī or "chief queen"), Padmavati, and Tishyarakshita.[36] He is similarly believed to have had four sons and two daughters: a son by Devi named Mahendra (Pali: Mahinda), Tivara (son of Karuvaki), Kunala (son of Padmavati, and Jalauka (mentioned in the Kashmir Chronicle), a daughter of Devi named Sanghamitra (Pali: Sanghamitta), and another daughter named Charumati.[36]

According to one version of the Mahavamsa, the Buddhist chronicle of Sri Lanka, Ashoka, when he was heir-apparent and was journeying as Viceroy to Ujjain, is said to have halted at Vidisha (10 kilometers from Sanchi), and there married the daughter of a local banker. She was called Devi and later gave Ashoka two sons, Ujjeniya and Mahendra, and a daughter Sanghamitta. After Ashoka's accession, Mahendra headed a Buddhist mission, sent probably under the auspices of the Emperor, to Sri Lanka.[37]

Conquest of Kalinga & Buddhist conversion

While the early part of Ashoka's reign was apparently quite bloodthirsty, he became a follower of the Buddha's teachings after his conquest of the Kalinga on the east coast of India in the present-day states of Odisha and North Coastal Andhra Pradesh. Kalinga was a state that prided itself on its sovereignty and democracy. With its monarchical parliamentary democracy it was quite an exception in ancient Bharata where there existed the concept of Rajdharma. Rajdharma means the duty of the rulers, which was intrinsically entwined with the concept of bravery and dharma. The Kalinga War happened eight years after his coronation. From his 13th inscription, we come to know that the battle was a massive one and caused the deaths of more than 100,000 soldiers and many civilians who rose up in defence; over 150,000 were deported.[39]

Edict 13 of the Edicts of Ashoka Rock Inscriptions expresses the great remorse the king felt after observing the destruction of Kalinga:

Directly after the Kalingas had been annexed began His Sacred Majesty’s zealous protection of the Law of Piety, his love of that Law, and his inculcation of that Law. Thence arises the remorse of His Sacred Majesty for having conquered the Kalingas, because the conquest of a country previously unconquered involves the slaughter, death, and carrying away captive of the people. That is a matter of profound sorrow and regret to His Sacred Majesty.[40]

Legend says that one day after the war was over, Ashoka ventured out to roam the city and all he could see were burnt houses and scattered corpses. The lethal war with Kalinga transformed the vengeful Emperor Ashoka to a stable and peaceful emperor and he became a patron of Buddhism. According to the prominent Indologist, A. L. Basham, Ashoka's personal religion became Buddhism, if not before, then certainly after the Kalinga war. However, according to Basham, the Dharma officially propagated by Ashoka was not Buddhism at all.[41] Nevertheless, his patronage led to the expansion of Buddhism in the Mauryan empire and other kingdoms during his rule, and worldwide from about 250 BCE.[42] Prominent in this cause were his son Mahinda (Mahendra) and daughter Sanghamitra (whose name means "friend of the Sangha"), who established Buddhism in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).[43]

Death and legacy

Ashoka ruled for an estimated 36 years and died in 232 BCE.[44] Legend states that during his cremation, his body burned for seven days and nights.[45] After his death, the Mauryan dynasty lasted just fifty more years until his empire stretched over almost all of the Indian subcontinent. Ashoka had many wives and children, but many of their names are lost to time. His chief consort (agramahisi) for the majority of his reign was his wife, Asandhimitra, who apparently bore him no children.[46]

In his old age, he seems to have come under the spell of his youngest wife Tishyaraksha. It is said that she had got Ashoka's son Kunala, the regent in Takshashila and the heir presumptive to the throne, blinded by a wily stratagem. The official executioners spared Kunala and he became a wandering singer accompanied by his favourite wife Kanchanmala. In Pataliputra, Ashoka heard Kunala's song, and realised that Kunala's misfortune may have been a punishment for some past sin of the emperor himself. He condemned Tishyaraksha to death, restoring Kunala to the court. In the Ashokavadana, Kunala is portrayed as forgiving Tishyaraksha, having obtained enlightenment through Buddhist practice. While he urges Ashoka to forgive her as well, Ashoka does not respond with the same forgiveness.[33] Kunala was succeeded by his son, Samprati, who ruled for 50 years until his death.

The reign of Ashoka Maurya might have disappeared into history as the ages passed by, had he not left behind records of his reign. These records are in the form of sculpted pillars and rocks inscribed with a variety of actions and teachings he wished to be published under his name. The language used for inscription was in one of the Prakrit "common" languages etched in a Brahmi script.[47]

In the year 185 BCE, about fifty years after Ashoka's death, the last Maurya ruler, Brihadratha, was assassinated by the commander-in-chief of the Mauryan armed forces, Pushyamitra Shunga, while he was taking the Guard of Honor of his forces. Pushyamitra Shunga founded the Shunga dynasty (185-75 BCE) and ruled just a fragmented part of the Mauryan Empire. Many of the northwestern territories of the Mauryan Empire (modern-day Afghanistan and Northern Pakistan) became the Indo-Greek Kingdom.

King Ashoka, the third monarch of the Indian Mauryan dynasty, is also considered as one of the most exemplary rulers who ever lived.[48]

Buddhist kingship

One of the more enduring legacies of Ashoka was the model that he provided for the relationship between Buddhism and the state. Emperor Ashoka was seen as a role model to leaders within the Buddhist community. He not only provided guidance and strength, but he also created personal relationships with his supporters.[49] Throughout Theravada Southeastern Asia, the model of rulership embodied by Ashoka replaced the notion of divine kingship that had previously dominated (in the Angkor kingdom, for instance). Under this model of 'Buddhist kingship', the king sought to legitimise his rule not through descent from a divine source, but by supporting and earning the approval of the Buddhist sangha. Following Ashoka's example, kings established monasteries, funded the construction of stupas, and supported the ordination of monks in their kingdom. Many rulers also took an active role in resolving disputes over the status and regulation of the sangha, as Ashoka had in calling a conclave to settle a number of contentious issues during his reign. This development ultimately led to a close association in many Southeast Asian countries between the monarchy and the religious hierarchy, an association that can still be seen today in the state-supported Buddhism of Thailand and the traditional role of the Thai king as both a religious and secular leader. Ashoka also said that all his courtiers always governed the people in a moral manner.

According to the legends mentioned in the 2nd-century CE text Ashokavadana, Ashoka was not non-violent after adopting Buddhism. In one instance, a non-Buddhist in Pundravardhana drew a picture showing the Buddha bowing at the feet of Nirgrantha Jnatiputra (identified with Mahavira, 24th Tirthankara of Jainism). On complaint from a Buddhist devotee, Ashoka issued an order to arrest him, and subsequently, another order to kill all the Ajivikas in Pundravardhana. Around 18,000 followers of the Ajivika sect were executed as a result of this order.[23][50] Sometime later, another Nirgrantha follower in Pataliputra drew a similar picture. Ashoka burnt him and his entire family alive in their house.[50] He also announced an award of one dinara (silver coin) to anyone who brought him the head of a Nirgrantha heretic. According to Ashokavadana, as a result of this order, his own brother was mistaken for a heretic and killed by a cowherd.[23] However, for several reasons, scholars say, these stories of persecutions of rival sects by Ashoka appear to be clear fabrications arising out of sectarian propaganda.[50][51][52]

Historical sources

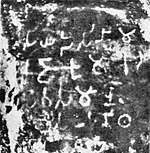

Ashoka had almost been forgotten, but in the 19th century James Prinsep contributed in the revelation of historical sources. After deciphering the Brahmi script, Prinsep had originally identified the "Priyadasi" of the inscriptions he found with the King of Ceylon Devanampiya Tissa. However, in 1837, George Turnour discovered an important Sri Lankan manuscript (Dipavamsa, or "Island Chronicle" ) associating Piyadasi with Ashoka:

"Two hundred and eighteen years after the beatitude of the Buddha, was the inauguration of Piyadassi, .... who, the grandson of Chandragupta, and the son of Bindusara, was at the time Governor of Ujjayani."

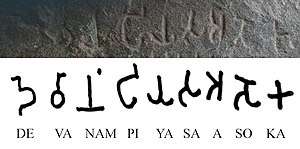

Since then, the association of "Devanampriya Priyadarsin" with Ashoka was confirmed through various inscriptions, and especially confirmed in the Minor Rock Edict inscription discovered in Maski, directly associating Ashoka with his regnal title Devanampriya ("Beloved-of-the-Gods"):[54][55]

[A proclamation] of Devanampriya Asoka.

Two and a half years [and somewhat more] (have passed) since I am a Buddha-Sakya.

[A year and] somewhat more (has passed) [since] I have visited the Samgha and have shown zeal.

Those gods who formerly had been unmingled (with men) in Jambudvipa, have how become mingled (with them).

This object can be reached even by a lowly (person) who is devoted to morality.

One must not think thus, — (viz.) that only an exalted (person) may reach this.

Both the lowly and the exalted must be told : "If you act thus, this matter (will be) prosperous and of long duration, and will thus progress to one and a half.

Another important historian was British archaeologist John Hubert Marshall, who was director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India. His main interests were Sanchi and Sarnath, in addition to Harappa and Mohenjodaro. Sir Alexander Cunningham, a British archaeologist and army engineer, and often known as the father of the Archaeological Survey of India, unveiled heritage sites like the Bharhut Stupa, Sarnath, Sanchi, and the Mahabodhi Temple. Mortimer Wheeler, a British archaeologist, also exposed Ashokan historical sources, especially the Taxila.

Information about the life and reign of Ashoka primarily comes from a relatively small number of Buddhist sources. In particular, the Sanskrit Ashokavadana ('Story of Ashoka'), written in the 2nd century, and the two Pāli chronicles of Sri Lanka (the Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa) provide most of the currently known information about Ashoka. Additional information is contributed by the Edicts of Ashoka, whose authorship was finally attributed to the Ashoka of Buddhist legend after the discovery of dynastic lists that gave the name used in the edicts (Priyadarshi—'He who regards everyone with affection') as a title or additional name of Ashoka Maurya. Architectural remains of his period have been found at Kumhrar, Patna, which include an 80-pillar hypostyle hall.

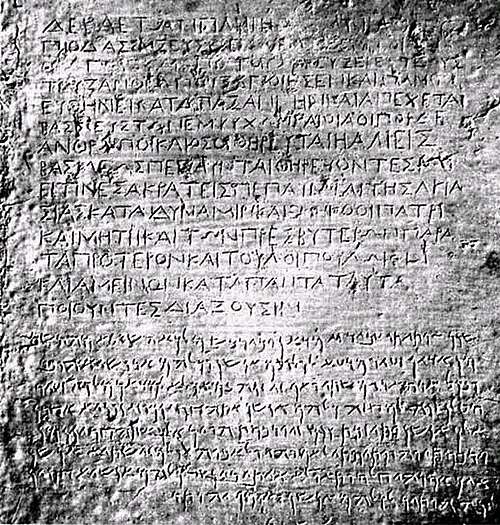

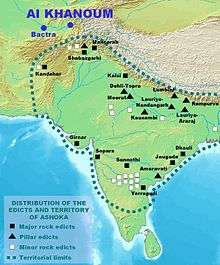

Edicts of Ashoka -The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of 33 inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, made by Ashoka during his reign. These inscriptions are dispersed throughout modern-day Pakistan and India, and represent the first tangible evidence of Buddhism. The edicts describe in detail the first wide expansion of Buddhism through the sponsorship of one of the most powerful kings of Indian history, offering more information about Ashoka's proselytism, moral precepts, religious precepts, and his notions of social and animal welfare.[57]

Ashokavadana – The Aśokāvadāna is a 2nd-century CE text related to the legend of Ashoka. The legend was translated into Chinese by Fa Hien in 300 CE. It is essentially a Hinayana text, and its world is that of Mathura and North-west India. The emphasis of this little known text is on exploring the relationship between the king and the community of monks (the Sangha) and setting up an ideal of religious life for the laity (the common man) by telling appealing stories about religious exploits. The most startling feature is that Ashoka’s conversion has nothing to do with the Kalinga war, which is not even mentioned, nor is there a word about his belonging to the Maurya dynasty. Equally surprising is the record of his use of state power to spread Buddhism in an uncompromising fashion. The legend of Veetashoka provides insights into Ashoka’s character that are not available in the widely known Pali records.[33]

.jpg)

Mahavamsa -The Mahavamsa ("Great Chronicle") is a historical poem written in the Pali language of the kings of Sri Lanka. It covers the period from the coming of King Vijaya of Kalinga (ancient Odisha) in 543 BCE to the reign of King Mahasena (334–361). As it often refers to the royal dynasties of India, the Mahavamsa is also valuable for historians who wish to date and relate contemporary royal dynasties in the Indian subcontinent. It is very important in dating the consecration of Ashoka.

Dwipavamsa -The Dwipavamsa, or "Dweepavamsa", (i.e., Chronicle of the Island, in Pali) is the oldest historical record of Sri Lanka. The chronicle is believed to be compiled from Atthakatha and other sources around the 3rd or 4th century CE. King Dhatusena (4th century) had ordered that the Dipavamsa be recited at the Mahinda festival held annually in Anuradhapura.

Symbolism

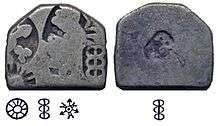

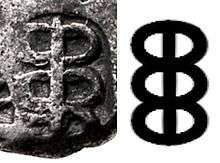

The caduceus appears as a symbol of the punch-marked coins of the Maurya Empire in India, in the 3rd-2nd century BCE. Numismatic research suggests that this symbol was the symbol of king Ashoka, his personal "Mudra".[59] This symbol was not used on the pre-Mauryan punch-marked coins, but only on coins of the Maurya period, together with the three arched-hill symbol, the "peacock on the hill", the triskelis and the Taxila mark.[60]

Perceptions and historiography

The use of Buddhist sources in reconstructing the life of Ashoka has had a strong influence on perceptions of Ashoka, as well as the interpretations of his Edicts. Building on traditional accounts, early scholars regarded Ashoka as a primarily Buddhist monarch who underwent a conversion to Buddhism and was actively engaged in sponsoring and supporting the Buddhist monastic institution. Some scholars have tended to question this assessment. Romila Thappar writes about Ashoka that "We need to see him both as a statesman in the context of inheriting and sustaining an empire in a particular historical period, and as a person with a strong commitment to changing society through what might be called the propagation of social ethics."[61] The only source of information not attributable to Buddhist sources are the Ashokan Edicts, and these do not explicitly state that Ashoka was a Buddhist. In his edicts, Ashoka expresses support for all the major religions of his time: Buddhism, Brahmanism, Jainism, and Ajivikaism, and his edicts addressed to the population at large (there are some addressed specifically to Buddhists; this is not the case for the other religions) generally focus on moral themes members of all the religions would accept. For example, Amartya Sen writes, "The Indian Emperor Ashoka in the third century BCE presented many political inscriptions in favor of tolerance and individual freedom, both as a part of state policy and in the relation of different people to each other".[62]

However, the edicts alone strongly indicate that he was a Buddhist. In one edict he belittles rituals, and he banned Vedic animal sacrifices; these strongly suggest that he at least did not look to the Vedic tradition for guidance. Furthermore, many edicts are expressed to Buddhists alone; in one, Ashoka declares himself to be an "upasaka", and in another he demonstrates a close familiarity with Buddhist texts. He erected rock pillars at Buddhist holy sites, but did not do so for the sites of other religions. He also used the word "dhamma" to refer to qualities of the heart that underlie moral action; this was an exclusively Buddhist use of the word. However, he used the word more in the spirit than as a strict code of conduct. Romila Thappar writes, "His dhamma did not derive from divine inspiration, even if its observance promised heaven. It was more in keeping with the ethic conditioned by the logic of given situations. His logic of Dhamma was intended to influence the conduct of categories of people, in relation to each other. Especially where they involved unequal relationships."[61] Finally, he promotes ideals that correspond to the first three steps of the Buddha's graduated discourse.[63]

The Ashokavadana presents an alternate view of the familiar Ashoka; one in which his conversion has nothing to do with the Kalinga war or about his descent from the Maurya dynasty. Instead, Ashoka's reason for adopting non-violence appears much more personal. The Ashokavadana shows that the main source of Ashoka's conversion and the acts of welfare that followed are rooted instead in intense personal anguish at its core, from a wellspring inside himself rather than spurred by a specific event. It thereby illuminates Ashoka as more humanly ambitious and passionate, with both greatness and flaws. This Ashoka is very different from the "shadowy do-gooder" of later Pali chronicles.[33]

Much of the knowledge about Ashoka comes from the several inscriptions that he had carved on pillars and rocks throughout the empire. All his inscriptions present him as compassionate and loving. In the Kalinga rock edits, he addresses his people as his "children" and mentions that as a father he desires their good.[64] These inscriptions promoted Buddhist morality and encouraged nonviolence and adherence to dharma (duty or proper behaviour), and they talk of his fame and conquered lands as well as the neighbouring kingdoms holding up his might. One also gets some primary information about the Kalinga War and Ashoka's allies plus some useful knowledge on the civil administration. The Ashoka Pillar at Sarnath is the most notable of the relics left by Ashoka. Made of sandstone, this pillar records the visit of the emperor to Sarnath, in the 3rd century BCE. It has a four-lion capital (four lions standing back to back), which was adopted as the emblem of the modern Indian republic. The lion symbolises both Ashoka's imperial rule and the kingship of the Buddha. In translating these monuments, historians learn the bulk of what is assumed to have been true fact of the Mauryan Empire. It is difficult to determine whether or not some events ever actually happened, but the stone etchings clearly depict how Ashoka wanted to be thought of and remembered.

Focus of debate

Recently scholarly analysis determined that the three major foci of debate regarding Ashoka involve the nature of the Maurya empire; the extent and impact of Ashoka's pacifism; and what is referred to in the Inscriptions as dhamma or dharma, which connotes goodness, virtue, and charity. Some historians have argued that Ashoka's pacifism undermined the "military backbone" of the Maurya empire, while others have suggested that the extent and impact of his pacifism have been "grossly exaggerated". The dhamma of the Edicts has been understood as concurrently a Buddhist lay ethic, a set of politico-moral ideas, a "sort of universal religion", or as an Ashokan innovation. On the other hand, it has also been interpreted as an essentially political ideology that sought to knit together a vast and diverse empire. Scholars are still attempting to analyse both the expressed and implied political ideas of the Edicts (particularly in regard to imperial vision), and make inferences pertaining to how that vision was grappling with problems and political realities of a "virtually subcontinental, and culturally and economically highly variegated, 3rd century BCE Indian empire. Nonetheless, it remains clear that Ashoka's Inscriptions represent the earliest corpus of royal inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent, and therefore prove to be a very important innovation in royal practices."[65]

Legends of Ashoka

Until the Ashokan inscriptions were discovered and deciphered, stories about Ashoka were based on the legendary accounts of his life and not strictly on historical facts. These legends were found in Buddhist textual sources such as the text of Ashokavadana. The Ashokavadana is a subset of a larger set of legends in the Divyavadana, though it could have existed independently as well. Following are some of the legends narrated in the Ashokavadana about Ashoka:

1) One of the stories talks about an event that occurred in a past life of Ashoka, when he was a small child named Jaya. Once when Jaya was playing on the roadside, the Buddha came by. The young child put a handful of earth in the Buddha’s begging bowl as his gift to the saint and declared his wish to one day become a great emperor and follower of the Buddha. The Buddha is said to have smiled a smile that “illuminated the universe with its rays of light”.[22] These rays of light are then said to have re-entered the Buddha’s left palm, signifying that this child Jaya would, in his next life, become a great emperor. The Buddha is said to have even turned to his disciple Ananda and is said to have predicted that this child would be “a great, righteous chakravarti king, who would rule his empire from his capital at Pataliputra”.

2) Another story aims to portray Ashoka as an evil person in order to convey the importance of his transformation into a good person upon adopting Buddhism.[22] It begins by stating that due to Ashoka’s physical ugliness he was disliked by his father Bindusara. Ashoka wanted to become king and so he got rid of the heir by tricking him into entering a pit filled with live coals. He became famous as “Ashoka the Fierce” because of his wicked nature and bad temper. He is said to have subjected his ministers to a test of loyalty and then have 500 of them killed for failing it. He is said to have burnt his entire harem to death when certain women insulted him. He is supposed to have derived sadistic pleasure from watching other people suffer. And for this he built himself an elaborate and horrific torture chamber where he amused himself by torturing other people. The story then goes on to narrate how it was only after an encounter with a pious Buddhist monk that Ashoka himself transformed into “Ashoka the pious”. A Chinese traveler who visited India in the 7th century CE, Xuan Zang recorded in his memoirs that he visited the place where the supposed torture chamber stood.

3) Another story is about events that occurred towards the end of Ashoka’s time on earth. Ashoka is said to have started gifting away the contents of his treasury to the Buddhist sangha. His ministers however were scared that his eccentricity would be the downfall of the empire and so denied him access to the treasury. As a result, Ashoka started giving away his personal possessions and was eventually left with nothing and so died peacefully.[22]

At this point it is important to note that the Ashokavadana being a Buddhist text in itself sought to gain new converts for Buddhism and so used all these legends. Devotion to the Buddha and loyalty to the sangha are stressed. Such texts added to the perception that Ashoka was essentially the ideal Buddhist monarch who deserved both admiration and emulation.[22]

Ashoka and the relics of the Buddha

According to Buddhist legend, particularly the Mahaparinirvana, the relics of the Buddha had been shared among eight countries following his death.[70] Ashoka endeavoured to take back the relics and share them among 84,000 stupas. This story is amply depicted in the reliefs of Sanchi and Bharhut.[71] According to the legend, Ashoka obtained the ashes from seven of the countries, but failed to take the ashes from the Nagas at Ramagrama. This scene is depicted on the tranversal portion of the southern gateway at Sanchi.

Contributions

Approach towards religions

According to Indian historian Romila Thapar, Ashoka emphasized respect for all religious teachers, and harmonious relationship between parents and children, teachers and pupils, and employers and employees.[73] Ashoka's religion contained gleanings from all religions. He emphasized the virtues of Ahimsa, respect to all religious teachers, equal respect for and study of each other's scriptures, and rational faith.

Global spread of Buddhism

As a Buddhist emperor, Ashoka believed that Buddhism is beneficial for all human beings as well as animals and plants, so he built a number of stupas, Sangharama, viharas, chaitya, and residences for Buddhist monks all over South Asia and Central Asia. According to the Ashokavadana, he ordered the construction of 84,000 stupas to house the Buddha's relics.[74] In the Aryamanjusrimulakalpa, Ashoka takes offerings to each of these stupas traveling in a chariot adorned with precious metals.[75] He gave donations to viharas and mathas. He sent his only daughter Sanghamitra and son Mahindra to spread Buddhism in Sri Lanka (then known as Tamraparni).

According to the Mahavamsa (XII, 1st paragraph),[76] in the 17th year of his reign, at the end of the Third Buddhist Council, Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to nine parts of the world (eight parts of Southern Asia, and the "country of the Yonas (Greeks)") to propagate Buddhism.[77]

.jpg)

Ashoka also invited Buddhists and non-Buddhists for religious conferences. He inspired the Buddhist monks to compose the sacred religious texts, and also gave all types of help to that end. Ashoka also helped to develop viharas (intellectual hubs) such as Nalanda and Taxila. Ashoka helped to construct Sanchi and Mahabodhi Temple. Ashoka also gave donations to non-Buddhists. As his reign continued his even-handedness was replaced with special inclination towards Buddhism.[78] Ashoka helped and respected both Shramanas (Buddhists monks) and Brahmins (Vedic monks). Ashoka also helped to organise the Third Buddhist council (c. 250 BCE) at Pataliputra (today's Patna), conducted by the monk Moggaliputta-Tissa.[79][80]

Emperor Ashoka's son, Mahinda, also helped with the spread of Buddhism by translating the Buddhist Canon into a language that could be understood by the people of Sri Lanka.[81]

It is well known that Ashoka sent dütas or emissaries to convey messages or letters, written or oral (rather both), to various people. The VIth Rock Edict about "oral orders" reveals this. It was later confirmed that it was not unusual to add oral messages to written ones, and the content of Ashoka's messages can be inferred likewise from the XIIIth Rock Edict: They were meant to spread his dhammavijaya, which he considered the highest victory and which he wished to propagate everywhere (including far beyond India). There is obvious and undeniable trace of cultural contact through the adoption of the Kharosthi script, and the idea of installing inscriptions might have travelled with this script, as Achaemenid influence is seen in some of the formulations used by Ashoka in his inscriptions. This indicates to us that Ashoka was indeed in contact with other cultures, and was an active part in mingling and spreading new cultural ideas beyond his own immediate walls.[82]

Hellenistic world

In his edicts, Ashoka mentions some of the people living in Hellenic countries as converts to Buddhism and recipients of his envoys, although no Hellenic historical record of this event remains:

Now it is conquest by Dhamma that Beloved-of-the-Gods considers to be the best conquest. And it (conquest by Dhamma) has been won here, on the borders, even six hundred yojanas away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni. Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamktis, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dhamma. Even where Beloved-of-the-Gods' envoys have not been, these people too, having heard of the practice of Dhamma and the ordinances and instructions in Dhamma given by Beloved-of-the-Gods, are following it and will continue to do so.

It is not too far-fetched to imagine, however, that Ashoka received letters from Greek rulers and was acquainted with the Hellenistic royal orders in the same way as he perhaps knew of the inscriptions of the Achaemenid kings, given the presence of ambassadors of Hellenistic kings in India (as well as the dütas sent by Ashoka himself).[82] Dionysius is reported to have been such a Greek ambassador at the court of Ashoka, sent by Ptolemy II Philadelphus,[87] who himself is mentioned in the Edicts of Ashoka as a recipient of the Buddhist proselytism of Ashoka. Some Hellenistic philosophers, such as Hegesias of Cyrene, who probably lived under the rule of King Magas, one of the supposed recipients of Buddhist emissaries from Asoka, are sometimes thought to have been influenced by Buddhist teachings.[88]

The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek (Yona) Buddhist monks, active in spreading Buddhism (the Mahavamsa, XII[89]).

Some Greeks (Yavana) may have played an administrative role in the territories ruled by Ashoka. The Girnar inscription of Rudradaman records that during the rule of Ashoka, a Yavana Governor was in charge in the area of Girnar, Gujarat, mentioning his role in the construction of a water reservoir.[90][91]

As administrator

Ashoka's military power was strong, but after his conversion to Buddhism, he maintained friendly relations with three major Tamil kingdoms in the South—namely, Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas—the post-Alexandrian empire, Tamraparni, and Suvarnabhumi. His edicts state that he made provisions for medical treatment of humans and animals in his own kingdom as well as in these neighbouring states. He also had wells dug and trees planted along the roads for the benefit of the common people.[64]

Animal welfare

Ashoka's rock edicts declare that injuring living things is not good, and no animal should be sacrificed for slaughter.[92] However, he did not prohibit common cattle slaughter or beef eating.[93]

He imposed a ban on killing of "all four-footed creatures that are neither useful nor edible", and of specific animal species including several birds, certain types of fish and bulls among others. He also banned killing of female goats, sheep and pigs that were nursing their young; as well as their young up to the age of six months. He also banned killing of all fish and castration of animals during certain periods such as Chaturmasa and Uposatha.[94][95]

Ashoka also abolished the royal hunting of animals and restricted the slaying of animals for food in the royal residence.[96] Because he banned hunting, created many veterinary clinics and eliminated meat eating on many holidays, the Mauryan Empire under Ashoka has been described as "one of the very few instances in world history of a government treating its animals as citizens who are as deserving of its protection as the human residents".[97]

Ashoka Chakra

The Ashoka Chakra (the wheel of Ashoka) is a depiction of the Dharmachakra (the Wheel of Dharma). The wheel has 24 spokes which represent the 12 Laws of Dependent Origination and the 12 Laws of Dependent Termination. The Ashoka Chakra has been widely inscribed on many relics of the Mauryan Emperor, most prominent among which is the Lion Capital of Sarnath and The Ashoka Pillar. The most visible use of the Ashoka Chakra today is at the centre of the National flag of the Republic of India (adopted on 22 July 1947), where it is rendered in a Navy-blue color on a White background, by replacing the symbol of Charkha (Spinning wheel) of the pre-independence versions of the flag. The Ashoka Chakra can also been seen on the base of the Lion Capital of Ashoka which has been adopted as the National Emblem of India.

The Ashoka Chakra was created by Ashoka during his reign. Chakra is a Sanskrit word which also means "cycle" or "self-repeating process". The process it signifies is the cycle of time—as in how the world changes with time.

A few days before India became independent in August 1947, the specially-formed Constituent Assembly decided that the flag of India must be acceptable to all parties and communities. A flag with three colours, Saffron, White and Green with the Ashoka Chakra was selected.[98]

Stone architecture

Ashoka is often credited with the beginning of stone architecture in India, possibly following the introduction of stone-building techniques by the Greeks after Alexander the Great.[99] Before Ashoka's time, buildings were probably built in non-permanent material, such as wood, bamboo or thatch.[99][100] Ashoka may have rebuilt his palace in Pataliputra by replacing wooden material by stone,[101] and may also have used the help of foreign craftmen.[102] Ashoka also innovated by using the permanent qualities of stone for his written edicts, as well as his pillars with Buddhist symbolism.

Pillars of Ashoka (Ashokstambha)

The pillars of Ashoka are a series of columns dispersed throughout the northern Indian subcontinent, and erected by Ashoka during his reign in the 3rd century BCE. Originally, there must have been many pillars of Ashoka although only ten with inscriptions still survive. Averaging between forty and fifty feet in height, and weighing up to fifty tons each, all the pillars were quarried at Chunar, just south of Varanasi and dragged, sometimes hundreds of miles, to where they were erected. The first Pillar of Ashoka was found in the 16th century by Thomas Coryat in the ruins of ancient Delhi. The wheel represents the sun time and Buddhist law, while the swastika stands for the cosmic dance around a fixed center and guards against evil.

Lion Capital of Ashoka (Ashokmudra)

The Lion capital of Ashoka is a sculpture of four lions standing back to back. It was originally placed atop the Ashoka pillar at Sarnath, now in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. The pillar, sometimes called the Ashoka Column, is still in its original location, but the Lion Capital is now in the Sarnath Museum. This Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath has been adopted as the National Emblem of India and the wheel ("Ashoka Chakra") from its base was placed onto the center of the National Flag of India.

The capital contains four lions (Indian / Asiatic Lions), standing back to back, mounted on a short cylindrical abacus, with a frieze carrying sculptures in high relief of an elephant, a galloping horse, a bull, and a lion, separated by intervening spoked chariot-wheels over a bell-shaped lotus. Carved out of a single block of polished sandstone, the capital was believed to be crowned by a 'Wheel of Dharma' (Dharmachakra popularly known in India as the "Ashoka Chakra"). The Sarnath pillar bears one of the Edicts of Ashoka, an inscription against division within the Buddhist community, which reads, "No one shall cause division in the order of monks."

The four animals in the Sarnath capital are believed to symbolise different steps of Lord Buddha's life.

- The Elephant represents the Buddha's idea in reference to the dream of Queen Maya of a white elephant entering her womb.

- The Bull represents desire during the life of the Buddha as a prince.

- The Horse represents Buddha's departure from palatial life.

- The Lion represents the accomplishment of Buddha.

Besides the religious interpretations, there are some non-religious interpretations also about the symbolism of the Ashoka capital pillar at Sarnath. According to them, the four lions symbolise Ashoka's rule over the four directions, the wheels as symbols of his enlightened rule (Chakravartin) and the four animals as symbols of four adjoining territories of India.

Constructions credited to Ashoka

The British restoration was done under guidance from Weligama Sri Sumangala.[103]

- Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh, India

- Dhamek Stupa, Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India

- Mahabodhi Temple, Bihar, India

- Barabar Caves, Bihar, India

- Nalanda Mahavihara (some portions like Sariputta Stupa), Bihar, India

- Taxila University (some portions like Dharmarajika Stupa and Kunala Stupa), Taxila, Pakistan

- Bhir Mound (reconstructed), Taxila, Pakistan

- Bharhut stupa, Madhya Pradesh, India

- Deorkothar Stupa, Madhya Pradesh, India

- Butkara Stupa, Swat, Pakistan

- Sannati Stupa, Karnataka, India: the only known sculptural depiction of Ashoka

- Mir Rukun Stupa, Nawabshah, Pakistan

In art, film and literature

- Jaishankar Prasad composed Ashoka ki Chinta (Ashoka's Anxiety), a poem that portrays Ashoka’s feelings during the war on Kalinga.

- Ashok Kumar is a 1941 Tamil film directed by Raja Chandrasekhar. The film stars Chittor V. Nagaiah as Ashoka.

- Uttar-Priyadarshi (The Final Beatitude), a verse-play written by poet Agyeya depicting his redemption, was adapted to stage in 1996 by theatre director, Ratan Thiyam and has since been performed in many parts of the world.[104][105]

- In 1973, Amar Chitra Katha released a graphic novel based on the life of Ashoka.

- In Piers Anthony’s series of space opera novels, the main character mentions Ashoka as a model for administrators to strive for.

- Aśoka is a 2001 epic Indian historical drama film directed and co-written by Santosh Sivan. The film stars Shah Rukh Khan as Ashoka.

- In 2002, Mason Jennings released the song "Emperor Ashoka" on his Living in the Moment EP. It is based on the life of Ashoka.

- In 2013, Christopher C. Doyle released his debut novel, The Mahabharata Secret, in which he wrote about Ashoka hiding a dangerous secret for the well-being of India.

- 2014's The Emperor's Riddles, a fiction mystery thriller novel by Satyarth Nayak, traces the evolution of Ashoka and his esoteric legend of the Nine Unknown Men.

- In 2015, Chakravartin Ashoka Samrat, a television serial by Ashok Banker, based on the life of Ashoka, began airing on Colors TV.

- The Legend of Kunal is an upcoming film based on the life of Kunal, the son of Ashoka. The movie will be directed by Chandraprakash Dwivedi. The role of Ashoka is to be played by Amitabh Bachchan, and the role of Kunal is played by Arjun Rampal.[106]

- Bharatvarsh (TV Series) is an Indian television historical documentary series, hosted by actor-director Anupam Kher on Hindi news channel ABP News.[107] The series stars Aham Sharma as Ashoka.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Lars Fogelin (1 April 2015). An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-0-19-994823-9.

- ↑ Fred Kleiner (1 January 2015). Gardner’s Art through the Ages: A Global History. Cengage Learning. pp. 474–. ISBN 978-1-305-54484-0.

- ↑ Lahiri 2015, pp. 295–296.

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780674975279.

- 1 2 3 Singh 2008, p. 331

- ↑ In his contemporary Maski Minor Rock Edict his name is written in the Brahmi script as Devanampriya Asoka. Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. pp. 174–175.

Asoka in the Maski Minor Rock Edict, c.259 BCE.

Asoka in the Maski Minor Rock Edict, c.259 BCE. - ↑ Chandra, Amulya (14 May 2015). "Ashoka | biography - emperor of India". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ↑ Thapar 1980, p. 51

- 1 2 Bentley 1993, p. 44

- ↑ Kalinga had been conquered by the preceding Nanda Dynasty but subsequently broke free until it was reconquered by Ashoka c. 260 BCE. (Raychaudhuri, H. C.; Mukherjee, B. N. 1996. Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. Oxford University Press, pp. 204-9, pp. 270-71)

- ↑ Bentley 1993, p. 45

- ↑ Bentley 1993, p. 46

- ↑ Nayanjot Lahiri (5 August 2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-0-674-91525-1.

- ↑ John S. Strong, The Legend of King Ashoka (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2014), 17.

- ↑ Chandragupta Maurya, EMPEROR OF INDIA, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. pp. 63–65. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- ↑ Roger Boesche (2003). The First Great Political Realist: Kautilya and His Arthashastra. Lexington Books. pp. 7–18. ISBN 978-0-7391-0607-5.

- ↑ The Early State, H. J. M. Claessen, Peter Skalník, Walter de Gruyter, 1978

- ↑ A Brief History of India, Alain Daniélou, Inner Traditions / Bear & Co, 2003, p.86-87

- ↑ Foreign Influence on Ancient India, Krishna Chandra Sagar, Northern Book Centre, 1992, p.83

- ↑ "Chandragupta married with a daughter of Suluva, the Yavana king of Pausasa. Thus, he mixed the Buddhists and the Yavanas. He ruled for 60 years. From him, Vindusara was born and ruled for the same number of years as his father. His son was Ashoka."

in Pratisarga Parva. Translation given in: Encyclopaedia of Indian Traditions and Cultural Heritage, Anmol Publications, 2009, p.18. Also online translation: Pratisarga Parva p.18 Archived 23 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Original Sanskrit of the first two verses given in Foreign Influence on Ancient India, Krishna Chandra Sagar, Northern Book Centre, 1992, p.83: "Chandragupta Sutah Paursadhipateh Sutam. Suluvasya Tathodwahya Yavani Baudhtatapar". - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Singh 2008, p. 332

- 1 2 3 Strong 1989, p. 232

- ↑ K. T. S. Sarao (2007). A text book of the history of Theravāda Buddhism (2 ed.). Department of Buddhist Studies, University of Delhi. p. 89. ISBN 978-81-86700-66-2.

- 1 2 Singh 2008, p. 333

- ↑ Ayyar 1987, p. 25.

- ↑ Gupta, The Origins of Indian Art, p.196

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of India

- 1 2 Allen, Charles (2012). Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor. Little, Brown Book Group. pp. 154–155. ISBN 9781408703885.

- ↑ Gyan Swarup Gupta (1 January 1999). India: From Indus Valley Civilisation to Mauryas. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-81-7022-763-2. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ Dolderer, Winfried (2017). "Der mitfühlende Monarch". Damals (in German). No. 12. pp. 60–63.

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780674975279.

- 1 2 3 4 Pradip Bhattacharya (2002). "The Unknown Ashoka". Boloji.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ Charles Drekmeier (1962). Kingship and Community in Early India. Stanford University Press. pp. 173–. ISBN 978-0-8047-0114-3. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ "The Truth of Babri Mosque". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- 1 2 Mookerji 1995, p. 9.

- ↑ Marshall, "A Guide to Sanchi" p.8ff Public Domain text

- 1 2 Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- ↑ prachin bharater itihas by sunil chattopadhyay

- ↑ Smith, Vincent (1920).

- ↑ Basham, A. L. (1954). The Wonder that was India: A Survey of the History and Culture of the Indian Sub-continent Before the Coming of the Muslims. London: Sidgwick and Jackson. p. 56. OCLC 181731857.

- ↑ Buckley, Edmund. Universal Religion. Chicago: The University Association. pp. 272–. ISBN 978-1-4400-8300-6.

- ↑ "Ashoka's son took Buddhism outside India". The Times of India. Times News Network. 16 March 2015. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ Kosmin 2014, p. 36.

- ↑ Strong, John (2007). Relics of the Buddha. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 149. ISBN 978-81-208-3139-1.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 82.

- ↑ Mudur, G.S. (16 May 2016). "Clues to undiscovered Ashoka inscriptions". Telegraph India. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam, Arun Tiwari. Guiding souls: dialogues on the purpose of life. Ocean Books. p. 47.

- ↑ Vesselin Popovski, Gregory M. Reichberg, and Nicholas Turner, World Religions and Norms of War (Tokyo: United Nations University Press, 2009), 66.

- 1 2 3 Beni Madhab Barua (5 May 2010). The Ajivikas. General Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-152-74433-2. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ Steven L. Danver (22 December 2010). Popular Controversies in World History: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions. ABC-CLIO. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ Le Phuoc (March 2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ Allen, Charles (2012). Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 79. ISBN 9781408703885.

- ↑ The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 42.

- ↑ Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2009). Ashoka. Penguin UK. p. 13. ISBN 9788184758078.

- ↑ Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Upinder Singh (2012). "Governing the State and the Self: Political Philosophy and Practice in the Edicts of As´oka". South Asian Studies. Routledge (28.2).

- ↑ Mitchiner, Michael (1978). Oriental Coins & Their Values: The Ancient and Classical World 600 B.C. - A.D. 650. Hawkins Publications. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-9041731-6-1.

- ↑ Indian Numismatics, Damodar Dharmanand Kosambi, Orient Blackswan, 1981, p.73

- ↑ Malwa Through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D, Kailash Chand Jain, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1972, p.134

- 1 2 Thappar, Romila (7–13 November 2009). "Ashoka - A Retrospective". Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (45): 31–37.

- ↑ Sen, Amartya (Summer 1998). "Universal Truths and the Westernizing Illusion". Harvard International Review. 20 (3): 40–43.

- ↑ Richard Robinson, Willard Johnson, and Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Buddhist Religions, fifth ed., Wadsworth 2005, page 59.

- 1 2 The Edicts of King Ashoka Archived 28 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine., English translation (1993) by Ven. S. Dhammika. ISBN 955-24-0104-6. Retrieved on: 21 February 2009

- ↑ Singh 2012

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 333. ISBN 9788131711200.

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780674975279.

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 333. ISBN 9788131711200.

- ↑ Thapar, Romila (2012). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780199088683.

- ↑ Asoka and the Buddha-Relics, T.W. Rhys Davids, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1901, pp. 397-410 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 July 1997. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ↑ Asiatic Mythology by J. Hackin p.84

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780674975279.

- ↑ Microsoft Encarta Article on Ashoka

- ↑ Strong 2007, pp. 136–137

- ↑ Strong 2007, p. 145

- ↑ Mahavamsa. "Chapter XII". lakdiva.org.

- ↑ Jermsawatdi, Promsak (1979). Thai Art with Indian Influences. Abhinav Publications. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9788170170907.

- ↑ N.V. Isaeva, Shankara and Indian philosophy. SUNY Press, 1993, page 24.

- ↑ Kinnard, Jacob N. (2010). The Emergence of Buddhism: Classical Traditions in Contemporary Perspective. Fortress Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780800697488.

- ↑ Allen, Charles (2012). Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 87. ISBN 9781408703885.

- ↑ Kate Crosby, Wiley-Blackwell Guides to Buddhism: Theravada Buddhism: Continuity, Diversity, and Identity (Somerset: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 84.

- 1 2 Oskar von Hinüber (2010). "Did Hellenistic Kings Send Letters to Aśoka?". Journal of the American Oriental Society. Freiburg (130.2): 262–265.

- ↑ Reference: "India: The Ancient Past" p.113, Burjor Avari, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-35615-6

- ↑ Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings. Harvard University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780674728820.

- ↑ Thomas Mc Evilly "The shape of ancient thought", Allworth Press, New York, 2002, p.368

- ↑ The Edicts of King Ashoka: an English rendering by Ven. S. Dhammika Archived 10 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Access to Insight: Readings in Theravāda Buddhism. Last accessed 1 September 2011.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, "The Natural History", 6, 21

- ↑ Preus, Anthony (2015). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Philosophy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-4422-4639-3.

- ↑ Full text of the Mahavamsa Click chapter XII Archived 5 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Foreign Influence on Ancient India by Krishna Chandra Sagar p.138

- ↑ The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archaeology by Upinder Singh p.18

- ↑ Fitzgerald 2004, p. 120.

- ↑ Simoons, Frederick J. (1994). Eat Not This Flesh: Food Avoidances from Prehistory to the Present (2nd ed.). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-299-14254-4.

- ↑ "The Edicts of King Asoka". Translated by Ven. S. Dhammika. Buddhist Publication Society. 1994. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016.

- ↑ D.R. Bhandarkar, R. G. Bhandarkar (2000). Asoka. Asian Educational Services. pp. 314–315.

- ↑ Gerald Irving A. Dare Draper; Michael A. Meyer; H. McCoubrey (1998). Reflections on Law and Armed Conflicts: The Selected Works on the Laws of War by the Late Professor Colonel G.I.A.D. Draper, Obe. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 44. ISBN 978-90-411-0557-8. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ Phelps, Norm (2007). The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to Peta. Lantern Books. ISBN 1590561066.

- ↑ Heimer, Željko (2 July 2006). "India". Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- 1 2 Introduction to Indian Architecture Bindia Thapar, Tuttle Publishing, 2012, p.21 "Ashoka used the knowledge of stone craft to begin the tradition of stone architecture in India, dedicated to Buddhism."

- ↑ Gardner's Art through the Ages: Non-Western Perspectives, Fred S. Kleiner, Cengage Learning, 2009, p14

- ↑ Mookerji 1995, p. 96.

- ↑ "Ashoka was known to be a great builder who may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments." Monuments, Power and Poverty in India: From Ashoka to the Raj, A. S. Bhalla, I.B.Tauris, 2015 p.18

- ↑ Goonatilake, Hema (30 May 2010). "Edwin Arnold and the Sri Lanka connection". The Sunday Times. Colombo. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013.

- ↑ Jefferson, Margo (27 October 2000). "Next Wave Festival Review; In Stirring Ritual Steps, Past and Present Unfold". The New York Times.

- ↑ Renouf, Renee (December 2000). "Review: Uttarpriyadarshi". Balletco. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "The Legend Of Kunal". filmifeat.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ "'Bharatvarsh' – ABP News brings a captivating saga of legendary Indians with Anupam Kher". 19 August 2016. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016.

Sources

- Ahir, D. C. (1995). Aśoka the Great. Delhi: B. R. Publishing.

- Allen, Charles (2012), Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor, Hachette, ISBN 978-1-408-70388-5

- Ayyar, Sulochana, Costumes and Ornaments as Depicted in the Sculptures of Gwalior Museum, Delhi: Mittal Publications, ISBN 81-7099-002-5

- Bentley, Jerry (1993). Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195076400.

- Bhandarkar, D.R. (1969). Aśoka (4th ed.). Calcutta: Calcutta University Press.

- Bongard-Levin, G. M. Mauryan India (Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division May 1986) ISBN 0-86590-826-5

- Chauhan, Gian Chand (2004). Origin and Growth of Feudalism in Early India: From the Mauryas to AD 650. Munshiram Manoharlal, Delhi. ISBN 978-81-215-1028-8

- Durant, Will (1935). Our Oriental Heritage. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Falk, Harry. Aśokan Sites and Artefacts – A Source-book with Bibliography (Mainz : Philipp von Zabern, [2006]) ISBN 978-3-8053-3712-0

- Fitzgerald, James L., ed. (2004), The Mahabharata, 7, The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-25250-7

- Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind (1996). Aśoka Maurya (Twayne Publishers) ISBN 978-0-8290-1735-9

- Hultzsch, Eugene (October 1914). "The Date of Asoka". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press: 943–951. JSTOR 25189238.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014), The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0

- Lahiri, Nayanjot (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674057777.

- Li Rongxi, trans. (1993). The biographical scripture of King Aśoka / transl. from the Chinese of Saṃghapāla, Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, ISBN 0-9625618-4-3.

- MacPhail, James Merry: "Aśoka", Calcutta: The Associative Press ; London: Oxford University Press 1918 PDF (5.9 MB)

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1928). Asoka (Gaekwad lectures). MacMillan.

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1995) [1962]. Aśoka (3rd Revised ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81208-058-28.

- Nikam, N. A.; McKeon, Richard (1959). The Edicts of Aśoka. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rice, B. Lewis (1889), Inscriptions at Sravana Belgola : a chief seat of the Jains, Bangalore: Mysore Govt. Central Press

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1967). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas. Reprint: 1996, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi. ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1

- Seneviratna, Anuradha (ed.), Gombrich, Richard; Guruge, Ananda (1994). King Aśoka and Buddhism: Historical and Literary studies, Kandy: Sri Lanka; Buddhist Publication Society, 1st edition, ISBN 9552400651

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A history of ancient and early medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131711200.

- Singh, Upinder (2012). "Governing the State and the Self: Political Philosophy and Practice in the Edicts of Aśoka". South Asian Studies. University of Delh. 28 (2): 131–145. doi:10.1080/02666030.2012.725581.

- Strong, John S. (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Strong, John (2007). Relics of the Buddha. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-3139-1.

- Swearer, Donald. Buddhism and Society in Southeast Asia (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania: Anima Books, 1981) ISBN 0-89012-023-4

- Thapar, Romila (1980) [1973]. Aśoka and the decline of the Mauryas (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. SBN 19-660379 6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashoka. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ashoka |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Asoka. |

- Ashoka at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- BBC Radio 4: Sunil Khilnani, Incarnations: Ashoka.

- BBC Radio 4: Melvyn Bragg with Richard Gombrich et al., In Our Time, Ashoka the Great.

- Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka: New Edition. Oxford: Government of India.

Ashoka Died: 232 BCE | ||

| Preceded by Bindusara |

Mauryan Emperor 272–232 BCE |

Succeeded by Dasharatha |

.jpg)