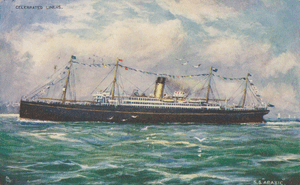

SS Arabic (1902)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Arabic |

| Owner: |

|

| Port of registry: |

|

| Route: | Liverpool, Queenstown, New York |

| Builder: | Harland and Wolff, Belfast, Ireland |

| Yard number: | 340 |

| Launched: | 18 December 1902 |

| Completed: | 21 June 1903 |

| Maiden voyage: | 26 June 1903 |

| Fate: | Torpedoed and sunk by U-24 19 August 1915 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 15,801 gross register tons (GRT) |

| Length: | 600 ft 7 in (183.06 m) |

| Beam: | 65 ft 5 in (19.94 m) |

| Propulsion: | quadruple expansion steam engines, twin screws |

| Speed: | 16 kn (30 km/h) |

| Capacity: | 1,400 Passengers: 200 First Class, 200 Second Class, 1,000 Third Class |

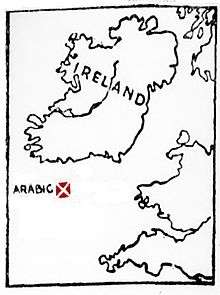

SS Arabic was a British-registered ocean liner that entered service in 1903 for the White Star Line. She was sunk on 19 August 1915, during the First World War, by German submarine SM U-24, 50 mi (80 km) south of Kinsale, causing a diplomatic incident.

Construction

_LOC_det.4a15792.jpg)

Arabic was originally intended to be Minnewaska, one of four ships ordered from Harland and Wolff, Belfast, Ireland, by the Atlantic Transport Line (ATL), but fell victim to the recession and the shipbuilding rationalization following the ATL's 1902 incorporation into the International Mercantile Marine Company, and was transferred before completion to the White Star Line as Arabic. She was extensively modified before launch with additional accommodation which extended her superstructure aft of her third mast and forward of her second mast. She had accommodations for 1,400 Passengers; 200 in First Class, 200 in Second Class and 1,000 in Third Class. Her accommodations were configured similar to most other White Star passenger ships, First Class amidships, Second Class abaft of First, and Third Class divided at the fore and after ends of the vessel.[1]

Career

Arabic commenced her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York City via Queenstown on 26 June 1903, arriving in New York on 5 July, marking the beginning of a 12-year career during which she spent half of on White Star's main route between Liverpool and New York, and the other half on White Star's secondary service to Boston, both of which included stops at Queenstown. She spent her first two years on the Liverpool-New York service before being transferred to the Boston route in April 1905, on which she sailed alongside Cymric and Republic for the next two years, while returning briefly to the New York route during the winter months. In the late spring of 1907, the White Star Line started their new express service out of Southampton, to which they transferred Teutonic, Majestic, Oceanic and the newly completed Adriatic, after which the Arabic was returned to the New York service to make up for this rearrangement. She remained on the New York service for the next four years, and after Olympic entered service in June 1911, she was again transferred back to the Boston route, on which she remained until White Star suspended their Liverpool-Boston service in November 1914 due to the escalation of the First World War, during which several of their ships were requisitioned by the British Navy for. She was transferred back to the New York service in January 1915, on which she remained until the end of her career the following August.[2]

Sinking

On 19 August 1915 U-24 sank the Arabic, outward bound for the United States, 50 mi (80 km) south of Kinsale. Arabic was zigzagging at the time, and the commander of U-24 said that he thought she was trying to ram his submarine. He fired a single torpedo which struck the liner aft, and she sank within 10 minutes, killing 44 passengers and crew, 3 of whom were American. On 22 August US President Wilson's press officer issued a statement to the effect that the White House staff was speculating on what to do if the Arabic investigation indicated that there had been a deliberate German attack. If true, there was speculation that the US would sever relations with Germany, while if it was untrue, negotiations were possible.

At the same time, US Secretary of State Robert Lansing approved Assistant Secretary Chandler Anderson's suggestion for a meeting with German Ambassador Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff to explain informally that if Germany abandoned submarine warfare, Britain would be the only violator of American neutral rights. Anderson met Bernstorff at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in New York and reported to Lansing that Bernstorff had immediately recognized the advantage of making Britain responsible for illegal acts unless Britain ended its war zone.

Following the Arabic incident, German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg and Foreign Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow decided to tell the Americans about their secret orders of 1 June and 5 June, which instructed submarine commanders not to torpedo passenger ships without notice and provisions for the safety of passengers and crew, and on 25 August Bethmann-Hollweg informed US Ambassador James W. Gerard about the June orders.

Bethmann-Hollweg and von Jagow also sought the Kaiser's approval to spare all passenger ships from submarine attack. This proposal angered the German admiralty, Alfred von Tirpitz offering to resign his post as Naval Secretary. The Kaiser rejected Tirpitz's offer and supported Bethmann and on 28 August the Chancellor issued new orders to submarine commanders and relayed them to Washington. The new orders stated that until further notice, all passenger ships could only be sunk after warning and the saving of passengers and crews. In his note to Bernstorff, Bethmann instructed him to negotiate as follows:[3]

- Offer Hague arbitration for the RMS Lusitania and Arabic incidents

- Passenger liners to be sunk only after warning and saving of lives, provided they do not flee or resist

- US to endeavour to reestablish free seas on the basis of the Declaration of London

Notes

References

- Haws, Duncan (1979). Merchant Fleets in Profile. 2. London: Pan.

- Smith, Eugene W (1978). Passenger Ships of the World Past and Present. New York: George H Dean Co. ISBN 99922-1-286-1.

External links

- 1915 NYTimes article about sinking of SS Arabic