Jallianwala Bagh massacre

| Jallianwala Bagh Massacre | |

|---|---|

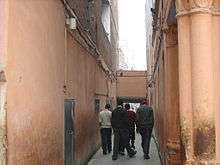

Narrow passage to Jallianwala Bagh Garden through which the shooting was conducted | |

Location of Amritsar in India | |

| Location | Amritsar, British India |

| Coordinates | 31°38′34″N 74°51′29″E / 31.64286°N 74.85808°ECoordinates: 31°38′34″N 74°51′29″E / 31.64286°N 74.85808°E |

| Date |

13 April 1919 17:37 (IST) |

| Target | Crowd of nonviolent protesters, along with Baisakhi pilgrims, who had gathered in Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar |

Attack type | Massacre |

| Weapons | Lee-Enfield rifles |

| Deaths | 379–1000[1] |

Non-fatal injuries | ~ 1,100 |

| Perpetrators | British Indian Army |

No. of participants | 50 |

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, also known as the Amritsar massacre, took place on 13 April 1919 when troops of the British Indian Army under the command of Colonel Reginald Dyer fired rifles into a crowd of Indians, who had gathered in Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar, Punjab. The civilians had assembled for a peaceful protest to condemn the arrest and deportation of two national leaders, Dr Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew. Even though the debate was peaceful and was conducted on the main Sikh festival Baisakhi with kids, women, and elders present, the Britishers debate over whether the crowd knew of the proclamation Dyer had made banning meetings, in its supposed inefficacy, however, Raja Ram has argued that the crowd formed in deliberate defiance, being the beginning of Indian nationalism.[2]

The Jallianwalla Bagh is a public garden of 6 to 7 acres (28,000 m2), walled on all sides, with five entrances.[3]

On Sunday, 13 April 1919, Dyer was convinced of a major insurrection and he banned all meetings; however this notice was not widely disseminated. That was the day of Baisakhi, the main Sikh festival, and many villagers had gathered in the Bagh. On hearing that a meeting had assembled at Jallianwala Bagh, Dyer went with Sikh, Gurkha, Baluchi, Rajput troops from 2-9th Gurkhas, the 54th Sikhs and the 59th Sind Rifles[4] they entered the garden, blocking the main entrance after them, took up position on a raised bank, and on Dyer's orders fired on the crowd for about ten minutes, directing their bullets largely towards the few open gates through which people were trying to flee, until the ammunition supply was almost exhausted. Dyer stated that approximately 1,650 rounds had been fired, a number apparently derived by counting empty cartridge cases picked up by the troops.[5] Official British Indian sources gave a figure of 379 identified dead,[6] with approximately 1,100 wounded. The casualty number estimated by the Indian National Congress was more than 1,500 injured, with approximately 1,000 dead.[7] This "brutality stunned the entire nation",[8] resulting in a "wrenching loss of faith" of the general public in the intentions of the UK.[9] The ineffective inquiry and the initial accolades for Dyer by the House of Lords fuelled widespread anger, leading to the Non-cooperation Movement of 1920–22.[10]

Dyer was initially lauded by conservative forces in the empire, but in July 1920 he was censured and forced to retire by the House of Commons.[11] He became a celebrated hero in the UK among most of the people connected to the British Raj,[12] for example, the House of Lords,[13] but unpopular in the House of Commons, which voted against Dyer as a Colonel. He was disciplined by being removed from his appointment, was passed over for promotion and was prohibited from further employment in India.[14][15] Upon his death, Rudyard Kipling declared that Dyer 'did his duty as he saw it'.[16] The massacre some historians have argued caused a re-evaluation of the army's role, in which the new policy became minimum force, however, later British actions during the Mau Mau insurgencies have led Huw Bennett to question this school of thought.[17] The army was retrained and developed less violent tactics for crowd control.[18] Some historians consider the episode a decisive step towards the end of British rule in India.[19]

Background

Defence of India Act

During World War I, British India contributed to the British war effort by providing men and resources. Millions of Indian soldiers and labourers served in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, while both the Indian administration and the princes sent large supplies of food, money, and ammunition. However, Bengal and Punjab remained sources of anticolonial activities. Revolutionary attacks in Bengal, associated increasingly with disturbances in Punjab, were significant enough to nearly paralyse the regional administration.[20][21] Of these, a pan-Indian mutiny in the British Indian Army planned for February 1915 was the most prominent amongst a number of plots formulated between 1914 and 1917 by Indian nationalists in India, the United States and Germany. The planned February mutiny was ultimately thwarted when British intelligence infiltrated the Ghadarite movement, arresting key figures. Mutinies in smaller units and garrisons within India were also crushed. In the scenario of the British war effort and the threat from the militant movement in India, the Defence of India Act 1915 was passed limiting civil and political liberties. Michael O'Dwyer, then the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, was one of the strongest proponents of the act, in no small part due to the Ghadarite threat in the province.[22]

Rowlatt act

The costs of the protracted war in money and manpower were great. High casualty rates in the war, increasing inflation after the end, compounded by heavy taxation, the deadly 1918 flu pandemic, and the disruption of trade during the war escalated human suffering in India. The pre-war Indian nationalist sentiment was revived as moderate and extremist groups of the Indian National Congress ended their differences to unify. In 1916, the Congress was successful in establishing the Lucknow Pact, a temporary alliance with the All-India Muslim League. British political concessions and Whitehall's India Policy after World War I began to change, with the passage of Montague–Chelmsford Reforms, which initiated the first round of political reform in the Indian subcontinent in 1917.[23][24][25] However, this was deemed insufficient in reforms by the Indian political movement. Mahatma Gandhi, recently returned to India, began emerging as an increasingly charismatic leader under whose leadership civil disobedience movements grew rapidly as an expression of political unrest. The recently crushed Ghadar conspiracy, the presence of Mahendra Pratap's Kabul mission in Afghanistan (with possible links to then nascent Bolshevik Russia), and a still-active revolutionary movement especially in Punjab and Bengal (as well as worsening civil unrest throughout India) led to the appointment of a Sedition committee in 1918 chaired by Sidney Rowlatt, an English judge. It was tasked to evaluate German and Bolshevik links to the militant movement in India, especially in Punjab and Bengal. On the recommendations of the committee, the Rowlatt Act, an extension of the Defence of India Act 1915, was enforced in India to limit civil liberties.[22][26][27][28][29]

The passage of the Rowlatt Act in 1919 precipitated large scale political unrest throughout India. Ominously, in 1919, the Third Anglo-Afghan War began in the wake of Amir Habibullah's assassination and institution of Amanullah in a system strongly influenced by the political figures courted by Kabul mission during the world war. As a reaction to Rowlatt act Muhammad Ali Jinnah resigned from his Bombay seat, writing to viceroy a letter, "I, therefor, as a protest against the passing of the Bill and the manner in which it was passed tender my resignation..................a government that passes or sanctions such a law in times of peace forfeits its claim to be called a civilized Government".[30] In India Gandhi's call for protest against the Rowlatt Act achieved an unprecedented response of furious unrest and protests. The situation especially in Punjab was deteriorating rapidly, with disruptions of rail, telegraph and communication systems. The movement was at its peak before the end of the first week of April, with some recording that "practically the whole of Lahore was on the streets, the immense crowd that passed through Anarkali was estimated to be around 20,000."[31] In Amritsar, over 5,000 people gathered at Jallianwala Bagh. This situation deteriorated perceptibly over the next few days. Michael O'Dwyer is said to have been of the firm belief that these were the early and ill-concealed signs of a conspiracy for a coordinated uprising around May, on the lines of the 1857 revolt, at a time when British troops would have withdrawn to the hills for the summer. The Amritsar massacre, as well as responses preceding and succeeding it, was the end result of a concerted plan of response from the Punjab administration to suppress such a conspiracy.[32]

Prelude

Many officers in the Indian army believed revolt was possible, and they prepared for the worst. In Amritsar, over 5,000 people gathered at Jallianwala Bagh. The British Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab, Michael O'Dwyer, is said to have believed that these were the early and ill-concealed signs of a conspiracy for a coordinated revolt around May, at a time when British troops would have withdrawn to the hills for the summer. The Amritsar massacre, as well as responses preceding and succeeding it, have been described by some historians as the end result of a concerted plan of response from the Punjab administration to suppress such a conspiracy.[32] James Houssemayne Du Boulay is said to have ascribed a direct relationship between the fear of a Ghadarite uprising in the midst of an increasingly tense situation in Punjab, and the British response that ended in the massacre.[33]

On 10 April 1919, there was a protest at the residence of the Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar, a city in Punjab, a large province in the northwestern part of India. The demonstration was to demand the release of two popular leaders of the Indian Independence Movement, Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew, who had been earlier arrested by the government and moved to a secret location. Both were proponents of the Satyagraha movement led by Gandhi. A military picket shot at the crowd, killing several protesters and setting off a series of violent events. Later the same day, several banks and other government buildings, including the Town Hall and the railway station, were attacked and set on fire. The violence continued to escalate, culminating in the deaths of at least five Europeans, including government employees and civilians. There was retaliatory shooting at crowds from the military several times during the day, and between eight and twenty people were killed.

On 11 April, Miss Marcella Sherwood, an English missionary, fearing for the safety of her pupils, was on her way to shut the schools and send the roughly 600 Indian children home.[13][34] While cycling through a narrow street called the Kucha Kurrichhan, she was caught by a mob, pulled to the ground by her hair, stripped naked, beaten, kicked, and left for dead. She was rescued by some local Indians, including the father of one of her pupils, who hid her from the mob and then smuggled her to the safety of Gobindgarh fort.[34][35] After visiting Sherwood on 19 April, the Raj's local commander, Colonel Dyer, issued an order requiring every Indian man using that street to crawl its length on his hands and knees.[13][36] Colonel Dyer later explained to a British inspector: "Some Indians crawl face downwards in front of their gods. I wanted them to know that a British woman is as sacred as a Hindu god and therefore they have to crawl in front of her, too."[37] He also authorised the indiscriminate, public whipping of locals who came within lathi length of British policemen. Miss Marcella Sherwood later defended Colonel Dyer, describing him "as the 'saviour' of the Punjab".[36]

For the next two days, the city of Amritsar was quiet, but violence continued in other parts of the Punjab. Railway lines were cut, telegraph posts destroyed, government buildings burnt, and three Europeans murdered. By 13 April, the British government had decided to put most of the Punjab under martial law. The legislation restricted a number of civil liberties, including freedom of assembly; gatherings of more than four people were banned.[38]

On the evening of 12 April, the leaders of the hartal in Amritsar held a meeting at the Hindu College - Dhab Khatikan. At the meeting, Hans Raj, an aide to Dr. Kitchlew, announced a public protest meeting would be held at 16:30 the following day in the Jallianwala Bagh, to be organised by a Dr. Muhammad Bashir and chaired by a senior and respected Congress Party leader, Lal Kanhyalal Bhatia. A series of resolutions protesting against the Rowlatt Act, the recent actions of the British authorities and the detention of Drs. Satyapal and Kitchlew was drawn up and approved, after which the meeting adjourned.[39]

Massacre

At 9:00 on the morning of 13 April, the traditional festival of Baisakhi, Colonel Reginald Dyer, the acting military commander for Amritsar and its environs, proceeded through the city with several city officials, announcing the implementation of a pass system to enter or leave Amritsar, a curfew beginning at 20:00 that night and a ban on all processions and public meetings of four or more persons. The proclamation was read and explained in English, Urdu, Hindi and Punjabi, but few paid it any heed or appear to have learned of it later.[40] Meanwhile, the local CID had received intelligence of the planned meeting in the Jallianwala Bagh through word of mouth and plainclothes detectives in the crowds. At 12:40, Dyer was informed of the meeting and returned to his base at around 13:30 to decide how to handle it.[41]

By mid-afternoon, thousands of Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus had gathered in the Jallianwala Bagh (garden) near the Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar. Many who were present had earlier worshipped at the Golden Temple, and were passing through the Bagh on their way home. The Bagh was (and is) an open area of six to seven acres, roughly 200 yards by 200 yards in size, and surrounded by walls roughly 10 feet in height. Balconies of houses three to four stories tall overlooked the Bagh, and five narrow entrances opened onto it, several with locked gates. During the rainy season, it was planted with crops, but served as a local meeting-area and playground for much of the year.[42] In the center of the Bagh was a samadhi (cremation site) and a large well partly filled with water which measured about 20 feet in diameter.[42]

Apart from pilgrims, Amritsar had filled up over the preceding days with farmers, traders and merchants attending the annual Baisakhi horse and cattle fair. The city police closed the fair at 14:00 that afternoon, resulting in a large number of people drifting into the Jallianwala Bagh. Dyer sent an aeroplane to overfly the Bagh and estimate the size of the crowd, that he reported was about 6,000, while the Hunter Commission estimates a crowd of 10,000 to 20,000 had assembled by the time of Dyer's arrival.[42][43] Colonel Dyer and Deputy Commissioner Irving, the senior civil authority for Amritsar, took no actions to prevent the crowd assembling, or to peacefully disperse the crowds. This would later be a serious criticism levelled at both Dyer and Irving.

An hour after the meeting began as scheduled at 16:30, Colonel Dyer arrived at the Bagh with a group of ninety Sikh, Gurkha, Baluchi (note that the Baluch Regiment of the British Indian Army did not have Baluch troops, the British having failed in their efforts to get the Baluch to enlist and serve; the Baluch continued to fight an insurgency of varying intensity with the British from 1839 to 1947. The Baluch regiment was staffed by troops from the Punjab and other areas of India), Rajput from 2-9th Gurkhas, the 54th Sikhs and the 59th Sind Rifles soldiers.[4] Fifty of them were armed with .303 Lee–Enfield bolt-action rifles. It is not clear whether Dyer had specifically chosen troops from that ethnic group due to their proven loyalty to the British or that they were simply the Sikh and non-Sikh units most readily available. He had also brought two armored cars armed with machine guns; however, the vehicles were left outside, as they were unable to enter the Bagh through the narrow entrances. The Jallianwala Bagh was surrounded on all sides by houses and buildings and had few narrow entrances. Most of them were kept permanently locked. The main entrance was relatively wide, but was guarded heavily by the troops backed by the armoured vehicles.

Dyer—without warning the crowd to disperse—blocked the main exits. He 'explained' later that this act "was not to disperse the meeting but to punish the Indians for disobedience."[44] Dyer ordered his troops to begin shooting toward the densest sections of the crowd. Firing continued for approximately ten minutes. Cease-fire was ordered only when ammunition supplies were almost exhausted, after approximately 1,650 rounds were spent.[5]

Many people died in stampedes at the narrow gates or by jumping into the solitary well on the compound to escape the shooting. A plaque, placed at the site after independence states that 120 bodies were removed from the well. The wounded could not be moved from where they had fallen, as a curfew was declared, and many more died during the night.[45]

Casualties

The number of casualties is disputed, with the Government of Punjab criticised by the Hunter Commission for not gathering accurate figures, and only offering an approximate figure of 200, and when interviewed by the members of the committee a senior civil servant in Punjab admitted that the actual figure could be higher.[43] The Sewa Samiti society independently carried out an investigation and reported 379 deaths, and 192 seriously wounded, which the Hunter Commission would base their figures of 379 deaths, and approximately 3 times this injured, suggesting 1500 casualties[43]. At the meeting of the Imperial Legislative Council held on 12 September 1919, the investigation led by Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya concluded that there were 42 boys among the dead, the youngest of them only 7 months old.[46] The Hunter commission confirmed the deaths of 337 men, 41 boys and a six-week old baby.[43]

In July 1919, three months after the massacre, officials were tasked with finding who had been killed by inviting inhabitants of the city to volunteer information about those who had died.[43] This information was incomplete due to fear that those who participated would be identified as having been present at the meeting, and some of the dead may not have had close relations in the area.[47]

Since the official figures were obviously flawed regarding the size of the crowd (6,000–20,000[43]), the number of rounds fired and the period of shooting, the Indian National Congress instituted a separate inquiry of its own, with conclusions that differed considerably from the British Government's inquiry. The casualty number quoted by the Congress was more than 1,500, with approximately 1,000 being killed.[48]

Indian nationalist, Swami Shraddhanand wrote to Gandhi of 1500 deaths in the incident.

The British Government tried to suppress information of the massacre, but news spread in India and widespread outrage ensued; details of the massacre did not become known in Britain until December 1919.

Aftermath

Colonel Dyer reported to his superiors that he had been "confronted by a revolutionary army", to which Major General William Beynon replied: "Your action correct and Lieutenant Governor approves."[49] O'Dwyer requested that martial law should be imposed upon Amritsar and other areas, and this was granted by Viceroy Lord Chelmsford.[50][51]

Both Secretary of State for War Winston Churchill and former Prime Minister H. H. Asquith however, openly condemned the attack, Churchill referring to it as "monstrous", while Asquith called it "one of the worst outrages in the whole of our history".[52] Winston Churchill, in the House of Commons debate of 8 July 1920, said, "The crowd was unarmed, except with bludgeons. It was not attacking anybody or anything… When fire had been opened upon it to disperse it, it tried to run away. Pinned up in a narrow place considerably smaller than Trafalgar Square, with hardly any exits, and packed together so that one bullet would drive through three or four bodies, the people ran madly this way and the other. When the fire was directed upon the centre, they ran to the sides. The fire was then directed to the sides. Many threw themselves down on the ground, the fire was then directed down on the ground. This was continued to 8 to 10 minutes, and it stopped only when the ammunition had reached the point of exhaustion."[53] After Churchill's speech in the House of Commons debate, MPs voted 247 to 37 against Dyer and in support of the Government.[54] Cloake reports that despite the official rebuke, many Britons "thought him a hero for saving the rule of British law in India."[55]

Rabindranath Tagore received the news of the massacre by 22 May 1919. He tried to arrange a protest meeting in Calcutta and finally decided to renounce his British knighthood as "a symbolic act of protest".[56] In the repudiation letter, dated 30 May 1919 and addressed to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, he wrote "I ... wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings."[57]

Gupta describes the letter written by Tagore as "historic". He writes that Tagore "renounced his knighthood in protest against the inhuman cruelty of the British Government to the people of Punjab", and he quotes Tagore's letter to the Viceroy "The enormity of the measures taken by the Government in the Punjab for quelling some local disturbances has, with a rude shock, revealed to our minds the helplessness of our position as British subjects in India ... [T]he very least that I can do for my country is to take all consequences upon myself in giving voice to the protest of the millions of my countrymen, surprised into a dumb anguish of terror. The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation..."[58] English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore Miscellaneous Writings Vol# 8 carries a facsimile of this hand written letter.[59]

Hunter Commission

On 14 October 1919, after orders issued by the Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, the Government of India announced the formation of a committee of inquiry into the events in Punjab. Referred to as the Disorders Inquiry Committee, it was later more widely known as the Hunter Commission. It was named after the chairman, William, Lord Hunter, former Solicitor-General for Scotland and Senator of the College of Justice in Scotland. The stated purpose of the commission was to "investigate the recent disturbances in Bombay, Delhi and Punjab, about their causes, and the measures taken to cope with them".[60] The members of the commission were:

- Lord Hunter, Chairman of the Commission

- Mr. Justice George C. Rankin of Calcutta

- Sir Chimanlal Harilal Setalvad, Vice-Chancellor of Bombay University and advocate of the Bombay High Court

- Mr W.F. Rice, member of the Home Department

- Major-General Sir George Barrow, KCB, KCMG, GOC Peshawar Division

- Pandit Jagat Narayan, lawyer and Member of the Legislative Council of the United Provinces

- Mr. Thomas Smith, Member of the Legislative Council of the United Provinces

- Sardar Sahibzada Sultan Ahmad Khan, lawyer from Gwalior State

- Mr H.C. Stokes, Secretary of the Commission and member of the Home Department[60]

After meeting in New Delhi on 29 October, the Commission took statements from witnesses over the following weeks. Witnesses were called in Delhi, Ahmedabad, Bombay and Lahore. Although the Commission as such was not a formally constituted court of law, meaning witnesses were not subject to questioning under oath, its members managed to elicit detailed accounts and statements from witnesses by rigorous cross-questioning. In general, it was felt the Commission had been very thorough in its enquiries.[60] After reaching Lahore in November, the Commission wound up its initial inquiries by examining the principal witnesses to the events in Amritsar.

On 19 November, Dyer was called to appear before the Commission. Although his military superiors had suggested he be represented by legal counsel at the inquiry, Dyer refused this suggestion and appeared alone.[60] Initially questioned by Lord Hunter, Dyer stated he had come to know about the meeting at the Jallianwala Bagh at 12:40 hours that day but did not attempt to prevent it. He stated that he had gone to the Bagh with the deliberate intention of opening fire if he found a crowd assembled there. Patterson says Dyer explained his sense of honour to the Hunter Commission by saying, "I think it quite possible that I could have dispersed the crowd without firing but they would have come back again and laughed, and I would have made, what I consider, a fool of myself."[61] Dyer further reiterated his belief that the crowd in the Bagh was one of "rebels who were trying to isolate my forces and cut me off from other supplies. Therefore, I considered it my duty to fire on them and to fire well".[60]

After Mr. Justice Rankin had questioned Dyer, Sir Chimanlal Setalvad enquired:

Sir Chimanlal: Supposing the passage was sufficient to allow the armoured cars to go in, would you have opened fire with the machine guns?

Dyer: I think probably, yes.

Sir Chimanlal: In that case, the casualties would have been much higher?

Dyer: Yes.[60]

Dyer further stated that his intentions had been to strike terror throughout the Punjab and in doing so, reduce the moral stature of the "rebels". He said he did not stop the shooting when the crowd began to disperse because he thought it was his duty to keep shooting until the crowd dispersed, and that a little shooting would not do any good. In fact he continued the shooting until the ammunition was almost exhausted.[62] He stated that he did not make any effort to tend to the wounded after the shooting: "Certainly not. It was not my job. Hospitals were open and they could have gone there."[63]

Exhausted from the rigorous cross-examination questioning and ill, Dyer was then released. Over the next several months, while the Commission wrote its final report, the British press, as well as many MPs, turned hostile towards Dyer as the extent of the massacre and his statements at the inquiry became widely known.[60] Lord Chelmsford refused to comment until the Commission had been wound up. In the meanwhile, Dyer, seriously ill with jaundice and arteriosclerosis, was hospitalised.[60]

Although the members of the Commission had been divided by racial tensions following Dyer's statement, and though the Indian members had written a separate, minority report, the final report, comprising six volumes of evidence and released on 8 March 1920, unanimously condemned Dyer's actions.[60] In "continuing firing as long as he did, it appears to us that General Dyer committed a grave error."[64] Dissenting members argued that the martial law regime's use of force was wholly unjustified. "General Dyer thought he had crushed the rebellion and Sir Michael O'Dwyer was of the same view", they wrote, "(but) there was no rebellion which required to be crushed." The report concluded that:

- Lack of notice to disperse from the Bagh in the beginning was an error.

- The length of firing showed a grave error.

- Dyer's motive of producing a sufficient moral effect was to be condemned.

- Dyer had overstepped the bounds of his authority.

- There had been no conspiracy to overthrow British rule in the Punjab.

The minority report of the Indian members further added that:

- Proclamations banning public meetings were insufficiently distributed.

- Innocent people were in the crowd, and there had been no violence in the Bagh beforehand.

- Dyer should have either ordered his troops to help the wounded or instructed the civil authorities to do so.

- Dyer's actions had been "inhuman and un-British" and had greatly injured the image of British rule in India.

The Hunter Commission did not impose any penal or disciplinary action because Dyer's actions were condoned by various superiors (later upheld by the Army Council).[65] The Legal and Home Members on the Viceroy's Council ultimately decided that, though Dyer had acted in a callous and brutal way, military or legal prosecution would not be possible due to political reasons. However, he was finally found guilty of a mistaken notion of duty and relieved of his command on 23 March. He had been recommended for a CBE as a result of his service in the Third Afghan War; this recommendation was cancelled on 29 March 1920.

Demonstration at Gujranwala

Two days later, on 15 April, demonstrations occurred in Gujranwala protesting the killings at Amritsar. Police and aircraft were used against the demonstrators, resulting in 12 deaths and 27 injuries. The Officer Commanding the Royal Air Force in India, Brigadier General N D K MacEwen stated later that:

I think we can fairly claim to have been of great use in the late riots, particularly at Gujranwala, where the crowd when looking at its nastiest was absolutely dispersed by a machine using bombs and Lewis guns.[66]

Assassination of Michael O'Dwyer

On 13 March 1940, at Caxton Hall in London, Udham Singh, an Indian independence activist from Sunam who had witnessed the events in Amritsar and had himself been wounded, shot and killed Michael O'Dwyer, the Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab at the time of the massacre, who had approved Dyer's action and was believed to have been the main planner.

Reginald Dyer was disciplined by being removed from his appointment, was passed over for promotion and was prohibited from further employment in India. He died in 1927[14]

Some, such as the nationalist newspaper Amrita Bazar Patrika, made statements supporting the killing. The common people and revolutionaries glorified the action of Udham Singh. Much of the press worldwide recalled the story of Jallianwala Bagh, and alleged O'Dwyer to have been responsible for the massacre. Singh was termed a "fighter for freedom" and his action was referred to in The Times newspaper as "an expression of the pent-up fury of the down-trodden Indian People".[67] In Fascist countries, the incident was used for anti-British propaganda: Bergeret, published in large scale from Rome at that time, while commenting upon the Caxton Hall assassination, ascribed the greatest significance to the circumstance and praised the action of Udham Singh as courageous.[68] The Berliner Börsen Zeitung termed the event "The torch of Indian freedom". German radio reportedly broadcast: "The cry of tormented people spoke with shots."

At a public meeting in Kanpur, a spokesman had stated that "at last an insult and humiliation of the nation had been avenged". Similar sentiments were expressed in numerous other places across the country.[69] Fortnightly reports of the political situation in Bihar mentioned: "It is true that we had no love lost for Sir Michael. The indignities he heaped upon our countrymen in Punjab have not been forgotten." In its 18 March 1940 issue Amrita Bazar Patrika wrote: "O'Dwyer's name is connected with Punjab incidents which India will never forget." The New Statesman observed: "British conservativism has not discovered how to deal with Ireland after two centuries of rule. Similar comment may be made on British rule in India. Will the historians of the future have to record that it was not the Nazis but the British ruling class which destroyed the British Empire?" Singh had told the court at his trial:

I did it because I had a grudge against him. He deserved it. He was the real culprit. He wanted to crush the spirit of my people, so I have crushed him. For full 21 years, I have been trying to wreak vengeance. I am happy that I have done the job. I am not scared of death. I am dying for my country. I have seen my people starving in India under the British rule. I have protested against this, it was my duty. What a greater honour could be bestowed on me than death for the sake of my motherland?[70]

Singh was hanged for the murder on 31 July 1940. At that time, many, including Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi, condemned the murder as senseless even if it was courageous. In 1952, Nehru (by then Prime Minister) honoured Udham Singh with the following statement, which appeared in the daily Partap:

I salute Shaheed-i-Azam Udham Singh with reverence who had kissed the noose so that we may be free.

Soon after this recognition by the Prime Minister, Udham Singh received the title of Shaheed, a name given to someone who has attained martyrdom or done something heroic on behalf of their country or religion.

Monument and legacy

A trust was founded in 1920 to build a memorial at the site after a resolution was passed by the Indian National Congress. In 1923, the trust purchased land for the project. A memorial, designed by American architect Benjamin Polk, was built on the site and inaugurated by President of India Rajendra Prasad on 13 April 1961, in the presence of Jawaharlal Nehru and other leaders. A flame was later added to the site.

The bullet marks remain on the walls and adjoining buildings to this day. The well into which many people jumped and drowned attempting to save themselves from the bullets is also a protected monument inside the park.

Formation of the Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee

Shortly following the massacre, the official Sikh clergy of the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) in Amritsar conferred upon Colonel Dyer the Saropa (the mark of distinguished service to the Sikh faith or, in general, humanity), sending shock waves among the Sikh community.[71] On 12 October 1920, students and faculty of the Amritsar Khalsa College called a meeting to demand the immediate removal of the Gurudwaras from the control of Mahants. The result was the formation of the Shiromani Gurudwara Prabhandak Committee on 15 November 1920 to manage and to implement reforms in Sikh shrines.[72]

Regret

Although Queen Elizabeth II had not made any comments on the incident during her state visits in 1961 and 1983, she spoke about the events at a state banquet in India on 13 October 1997:[73]

It is no secret that there have been some difficult episodes in our past – Jallianwala Bagh, which I shall visit tomorrow, is a distressing example. But history cannot be rewritten, however much we might sometimes wish otherwise. It has its moments of sadness, as well as gladness. We must learn from the sadness and build on the gladness.[73]

On 14 October 1997, Queen Elizabeth II visited Jallianwala Bagh and paid her respects with a 30‑second moment of silence. During the visit, she wore a dress of a colour described as pink apricot or saffron, which was of religious significance to the Sikhs.[73] She removed her shoes while visiting the monument and laid a wreath at the monument.[73]

While some Indians welcomed the expression of regret and sadness in the Queen's statement, others criticised it for being less than an apology.[73] The then Prime Minister of India Inder Kumar Gujral defended the Queen, saying that the Queen herself had not even been born at the time of the events and should not be required to apologise.[73]

Controversies

The Queen's 1997 statement was not without controversies. During her visit, there were protests brewing in the city of Amritsar outside, people chanting slogans "Queen, go back."[74] Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh merely signed on the visitor's book. The fact that they did not leave any comment, leave aside, even regretting the incident was criticized.[75][76]

During the same visit, minutes after Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip stood in silence at the Flame of Liberty, the Duke of Edinburgh and his guide, Partha Sarathi Mukherjee, reached a plaque recording the events of the 1919 massacre. Among the many things found on the plaque was the assertion that 2,000 people were killed by Gen. Dyer's troops. (The precise text is: "This place is saturated with the blood of about two thousand Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims who were martyred in a non-violent struggle." It goes on to describe the events of that day.)[77] "That's a bit exaggerated," Philip told Mukherjee, "it must include the wounded." Mukherjee asked Philip how he had come to this conclusion. "I was told about the killings by General Dyer's son," Mukherjee recalls the Duke as saying, "I'd met him while I was in the Navy." These statements by Philip drew widespread condemnation in India.[77][76][78][79] Indian journalist Praveen Swami wrote in the Frontline magazine: "(The fact that)... this was the solitary comment Prince Philip had to offer after his visit to Jallianwala Bagh... (and that) it was the only aspect of the massacre that exercised his imagination, caused offence. It suggested that the death of 379 people was in some way inadequate to appall the royal conscience, in the way the death of 2,000 people would have. Perhaps more important of all, the staggering arrogance that Prince Philip displayed in citing his source of information on the tragedy made clear the lack of integrity in the wreath-laying."[77]

Demands for apology

There are long-standing demands in India that Britain should apologize for the massacre.[77][76][80][75] Winston Churchill, on 8 July 1920, urged the House of Commons to punish Colonel Dyer.[53] Churchill succeeded in persuading the House to forcibly retire Colonel Dyer, but Churchill would have preferred to have seen the colonel disciplined.[54]

In February 2013 David Cameron became the first serving British Prime Minister to visit the site, laid a wreath at the memorial, and described the Amritsar massacre as "a deeply shameful event in British history, one that Winston Churchill rightly described at that time as monstrous. We must never forget what happened here and we must ensure that the UK stands up for the right of peaceful protests". Cameron did not deliver an official apology.[81] This was criticized by some commentators. Writing in The Telegraph, Sankarshan Thakur wrote, "Over nearly a century now British protagonists have approached the 1919 massacre ground of Jallianwala Bagh thumbing the thesaurus for an appropriate word to pick. 'Sorry' has not been among them."

The issue of apology resurfaced during the 2016 India visit of Prince William and Kate Middleton when both decided to skip the memorial site from their itinerary.[82] In 2017, Indian author and politician Shashi Tharoor suggested that the Jalianwala Bagh centenary in 2019 should be a "good time" for the British to apologise to the Indians for wrongs committed during the colonial rule.[83][80] Visiting the memorial on 6 December 2017, London's mayor Sadiq Khan called on the British government to apologize for the massacre.[84]

In popular culture

- 1932: Noted Hindi poet Subhadra Kumari Chauhan wrote a poem, "Jallianwalla Bagh Mein Basant",[85] (Spring in the Jallianwalla Bagh) in memory of the slain in her anthology Bikhre Moti (Scattered Pearls).

- 1977: The massacre is portrayed in the Hindi movie Jallian Wala Bagh starring Vinod Khanna, Parikshat Sahni, Shabana Azmi, Sampooran Singh Gulzar, and Deepti Naval. The film was written, produced and directed by Balraj Tah with the screenplay by Gulzar. The film is a part-biopic of Udham Singh (played by Parikshit Sahni) who assassinated Michael O'Dwyer in 1940. Portions of the film were shot in the UK notably in Coventry and surrounding areas.[86]

- 1981: Salman Rushdie's novel Midnight's Children portrays the massacre from the perspective of a doctor in the crowd, saved from the gunfire by a well-timed sneeze.

- 1982: The massacre is depicted in Richard Attenborough's film Gandhi with the role of General Dyer played by Edward Fox. The film depicts most of the details of the massacre as well as the subsequent inquiry by the Montague commission.

- 1984: The story of the massacre also occurs in the 7th episode of Granada TV's 1984 series The Jewel in the Crown, recounted by the fictional widow of a British officer who is haunted by the inhumanity of it and who tells how she came to be reviled because she defied the honours to Dyer and instead donated money to the Indian victims.

- 2002: In the Hindi movie The Legend of Bhagat Singh directed by Rajkumar Santoshi, the massacre is reconstructed with the child Bhagat Singh as a witness, eventually inspiring him to become a revolutionary in the Indian independence movement.

- 2006: Portions of the Hindi movie Rang De Basanti nonlinearly depict the massacre and the influence it had on the freedom fighters.

- 2009: Bali Rai's novel, City of Ghosts, is partly set around the massacre, blending fact with fiction and magical realism. Dyer, Udham Singh and other real historical figures feature in the story.

- 2012: A few shots of the massacre are captured in the movie Midnight's Children, a Canadian-British film adaptation of Salman Rushdie's 1981 novel of the same name directed by Deepa Mehta.

- 2014: The British period drama Downton Abbey makes a reference to the massacre in the eighth episode of season 5 as "that terrible Amritsar business". The characters of Lord Grantham, Isobel Crawley and Shrimpy express their disapproval of the massacre when Susan MacClare and Lord Sinderby support it.

- 2017: The Hindi language movie Phillauri references the massacre as the reason the spirit of the primary character portrayed by Anushka Sharma cannot find peace as her lover lost his life in Amritsar and was unable to return to their village for their wedding. The movie depicts the massacre and the following stampede, with the climax shot on-location at the modern-day Jallianwallah Bagh memorial.

See also

- Vidurashwatha

- British Raj

- Babrra massacre

- Massacre of Chumik Shenko

- Indian independence movement

- List of massacres in India

- Bloody Sunday, a day of IRA assassinations in Ireland and revenge attacks by the Royal Irish Constabulary on a crowd at Croke Park and on prisoners at Dublin Castle

- Mahatma Gandhi

- Jinnah

References

- ↑ "1919 Jallianwalla Bagh massacre". Discover Sikhism. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ Raja Ram, The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre: A Premeditated Plan, p. 160.

- ↑ Report of Commissioners, Vol I, II, Bombay, 1920, Reprint New Delhi, 1976, p 56.

- 1 2 "Punjab disturbances, April 1919; compiled from the Civil and military gazette". Lahore Civil and Military Gazette Press. 9 April 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 Nigel Collett (15 October 2006). The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer. A&C Black. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-85285-575-8.

- ↑ Nigel Collett (15 October 2006). The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer. A&C Black. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-85285-575-8.

- ↑ Brian Lapping, End of Empire, p. 38, 1985

- ↑ Bipan Chandra etal, India's Struggle for Independence, Viking 1988, p.166

- ↑ Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf (2006). A concise history of modern India. Cambridge University Press. p.169

- ↑ Collett, Nigel (2006). The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer. pp. 398–399.

- ↑ Manchester, William. The Last Lion: Winston S Churchill, Visions of Glory (1874–1932). Little, Brown. p. 694.

- ↑ Derek Sayer, "British Reaction to the Amritsar Massacre 1919–1920", Past & Present',' May 1991, Issue 131, pp 130–164

- 1 2 3 Jaswant Singh (13 April 2002). "Bloodbath on the Baisakhi". The Tribune. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- 1 2 "ARMY COUNCIL AND GENERAL DYER. (Hansard, 8 July 1920)". hansard.millbanksystems.com.

- ↑ Manchester, William. The Last Lion : Winston Spencer Churchill, Visions of Glory (1874–1932). Little, Brown. p. 694.

- ↑ Nigel Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar, p. 430.

- ↑ Huw Bennett, Fighting the Mau Mau: The British Army and Counter-Insurgency in the Kenya

- ↑ Srinath Raghaven, "Protecting the Raj: The Army in India and Internal Security, c . 1919–39", Small Wars and Insurgencies, (Fall 2005), 16#3 pp 253–279 online

- ↑ Brain Bond, "Amritsar 1919", History Today, Sept 1963, Vol. 13 Issue 10, pp 666–676

- ↑ Gupta, Amit Kumar (Sep–Oct 1997). "Defying Death: Nationalist Revolutionism in India, 1897-1938". Social Scientist. 25 (9/10): 12. doi:10.2307/3517678. JSTOR 3517678.

- ↑ Popplewell, Richard J. (1995). Intelligence and Imperial Defence: British Intelligence and the Defence of the Indian Empire 1904–1924. Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 0-7146-4580-X.

- 1 2 Popplewell, Richard J. (1995). Intelligence and Imperial Defence: British Intelligence and the Defence of the Indian Empire 1904–1924. Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 0-7146-4580-X.

- ↑ Majumdar, Ramesh C. (1971). History of the Freedom Movement in India. II. Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay. p. xix. ISBN 81-7102-099-2.

- ↑ Dignan, Don (February 1971). "The Hindu Conspiracy in Anglo-American Relations during World War I". The Pacific Historical Review. University of California Press. 40 (1): 60. doi:10.2307/3637829.

- ↑ Cole, Howard; et al. (2001). Labour and Radical Politics 1762–1937. Routledge. p. 572. ISBN 0-415-26576-2.

- ↑ Lovett, Sir Verney (1920). A History of the Indian Nationalist Movement. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company. pp. 94, 187–191. ISBN 81-7536-249-9.

- ↑ Sarkar, B. K. (March 1921). "The Hindu Theory of the State". Political Science Quarterly. The Academy of Political Science. 36 (1): 137.

- ↑ Tinker, Hugh (October 1968). "India in the First World War and after". Journal of Contemporary History. Sage Publications. 3 (4): 92. JSTOR 259846.

- ↑ Fisher, Margaret W. (Spring 1972). "Essays on Gandhian Politics: the Rowlatt Satyagraha of 1919 (in Book Reviews)". Pacific Affairs. University of British Columbia. 45 (1): 129. doi:10.2307/2755297.

- ↑ Wolpert, Stanley (2013). Jinnah of Pakistan. Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-19-577389-7.

- ↑ Swami P (November 1, 1997). "Jallianwala Bagh revisited". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- 1 2 Cell, John W. (2002). Hailey: A Study in British Imperialism, 1872–1969. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-521-52117-3.

- ↑ Brown, Emily (May 1973). "Book Reviews; South Asia". The Journal of Asian Studies. University of British Columbia. 32 (3): 523. doi:10.2307/2052702.

- 1 2 Ferguson, Niall (2003). Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World. London: Penguin Books. p. 326. ISBN 0-7139-9615-3.

- ↑ Collett, Nigel (2006). The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer. Hambledon Continuum: New Edition. p. 234.

- 1 2 Banerjee, Sikata (2012). Muscular Nationalism: Gender, Violence, and Empire. p. 24.

- ↑ Talbott, Strobe (2004). Engaging India : Diplomacy, Democracy, and the Bomb. p. 245.

- ↑ Townshend, Britains Civil Wars. p137

- ↑ Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar p. 246

- ↑ Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar p. 252-253

- ↑ Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar p. 253

- 1 2 3 Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar p. 254-255

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 India. Committee on Disturbances in Bombay, Delhi, and the Punjab (1920). Report; disorders inquiry committee 1919-1920. pp. XX–XXI, 44–45, 116–7. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer p 255-58

- ↑ Collett, Nigel (2006). The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer. Hambledon Continuum: New Edition. p. 254-255

- ↑ Datta, Vishwa Nath (1969). Jallianwala Bagh. [Kurukshetra University Books and Stationery Shop for] Lyall Book Depot.

- ↑ Nigel Collett (2007). The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer. Hambledon and London. p. 263.

- ↑ "Amritsar Massacre – ninemsn Encarta". Archived from the original on 1 November 2009.

- ↑ Nigel Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer (2006) p. 267

- ↑ Derek Sayer, "British Reaction to the Amritsar Massacre 1919–1920", Past & Present, May 1991, Issue 131, p.142

- ↑ Nigel Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer (2006) p. 372

- ↑ Derek Sayer, "British Reaction to the Amritsar Massacre 1919–1920", Past & Present, May 1991, Issue 131, p.131

- 1 2 "Hansard (House of Commons Archives)". Hansard: 1719–1733. 8 July 1920.

- 1 2 Manchester, William (1988). The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Visions of Glory (1874–1932). Little, Brown. p. 694.

- ↑ J. A. Cloake (1994). Britain in the Modern World. Oxford University Press. p. 36.

- ↑ Rabindranath Tagore; Sisir Kumar Das (January 1996). A miscellany. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 982–. ISBN 978-81-260-0094-4. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ↑ "Tagore renounced his Knighthood in protest for Jalianwalla Bagh mass killing". The Times of India. Mumbai: Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd. 13 April 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ↑ Kalyan Sen Gupta (2005). The philosophy of Rabindranath Tagore. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-7546-3036-4. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ↑ Rabindranath Tagore; Introduction By Mohit K. Ray (1 January 2007). English Writings of Rabindranath TagoreMiscellaneous Writings Vol# 8. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 1021–. ISBN 978-81-269-0761-8. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Collett, Nigel (2006). The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer. Amritsar (India): Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 333–334. ISBN 9781852855758.

- ↑ Steven Patterson, The cult of imperial honor in British India (2009) P. 67

- ↑ Nick Lloyd, The Amritsar Massacre: The Untold Story of One Fateful Day (2011) p. 157

- ↑ Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar p. 337

- ↑ Cyril Henry Philips, "The evolution of India and Pakistan, 1858 to 1947: select documents" p.214. Oxford University Press, 1962

- ↑ Winston Churchill (8 July 1920). "Winston Churchill's speech in the House of Commons". Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ↑ "Royal Air Force Power Review" (PDF). 1. Spring 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ The Times, London, 16 March 1940

- ↑ Public and Judicial Department, File No L/P + J/7/3822, Caxton Hall outrage, India Office Library and Records, London, pp 13–14

- ↑ Government of India, Home Department, Political File No 18/3/1940, National Archives of India, New Delhi, p40

- ↑ CRIM 1/1177, Public Record Office, London, p 64

- ↑ Ajit Singh Sarhadi, "Punjabi Suba: The Story of the Struggle", Kapur Printing Press, Delhi, 1970, p. 19.

- ↑ Indian critiques of Gandhi – Google Books. Books.google.com. 2003. ISBN 978-0-7914-5910-2. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Burns, John F. (15 October 1997). "In India, Queen Bows Her Head Over a Massacre in 1919". New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Rediff On The NeT: Queen visits Jallianwalla Bagh". www.rediff.com.

- 1 2 "Jallianwala Bagh massacre anniversary: Is it time for Britain to apologise for excesses committed on Indians?". India Today.

- 1 2 3 "History repeats itself, in stopping short".

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl1422/14220460.htm

- ↑ "Rediff On The NeT: Prince Philip kicks up another storm". m.rediff.com.

- ↑ Burns, John F. (19 October 1997). "India and England Beg to Differ; Tiptoeing Through the Time of the Raj" – via NYTimes.com.

- 1 2 "Jallianwala Bagh centenary a 'good time' for British to apologise: Shashi Tharoor". 15 January 2017.

- ↑ "David Cameron marks British 1919 Amritsar massacre". News. BBC. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013. "Not our finest hour: David Cameron to visit Amritsar massacre site but won't make official apology". News. Daily Mirror. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013. "Jallianwala Bagh killings shameful, says David Cameron". News. Daily News and Analysis. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "Jallianwala Bagh : The shrine Kate and Will should not have given a miss".

- ↑ "When will a British PM beg forgiveness for Jallianwala Bagh massacre?". www.dailyo.in.

- ↑ "Britain must apologise for Jallianwala Bagh massacre: London Mayor Sadiq Khan". 6 December 2017 – via The Economic Times.

- ↑ "जलियाँवाला बाग में बसंत / सुभद्राकुमारी चौहान - कविता कोश". kavitakosh.org.

- ↑ Jallian Wala Bagh on IMDb

Further reading

- Collett, Nigel (2006). The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer.

- Draper, Alfred (1985). The Amritsar Massacre: Twilight of the Raj.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1997). Like Hidden Fire: The Plot to Bring Down the British Empire. Kodansha Globe. ISBN 1-56836-127-0.

- Judd, Dennis (1996). "The Amritsar Massacre of 1919: Gandhi, the Raj and the Growth of Indian Nationalism, 1915–39", in Judd, Empire: The British Imperial Experience from 1765 to the Present. Basic Books. pp 258– 72.

- Lloyd, Nick (2011). The Amritsar Massacre: The Untold Story of One Fateful Day.

- Narain, Savita (1998). The historiography of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, 1919. New Delhi: Spantech and Lancer. 76pp. ISBN 1-897829-36-1

- Swinson, Arthur (1964). Six Minutes to Sunset: The Story of General Dyer and the Amritsar Affair. London: Peter Davies.

- Wagner, Kim A. "Calculated to Strike Terror': The Amritsar Massacre and the Spectacle of Colonial Violence." Past Present (2016) 233#1: 185-225. doi: 10.1093/pastj/gtw037

External links

- Debate on this incident in the British Parliament.

- An NPR interview with Bapu Shingara Singh – the last known surviving witness.

- Churchill's speech after the incident.

- Amritsar Massacre at Jallianwala Bagh Listen to the Shaheed song of the Amritsar Massacre at Jallian Wala Bagh.

- Amritsar Massacre as a turning point in the British Raj – Description and analysis of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre.