Alex Turner

| Alex Turner | |

|---|---|

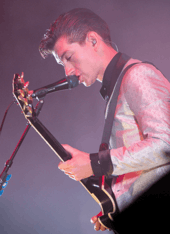

Turner performing in San Francisco in 2011 | |

| Born |

Alexander David Turner 6 January 1986 High Green, Sheffield, England |

| Residence | Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 2002–present |

| Labels | Domino |

| Associated acts | |

Alexander David Turner (born 6 January 1986) is an English musician, singer, songwriter and record producer. He is best known as the frontman and principal songwriter of the rock band Arctic Monkeys, with whom he has released six albums. Turner has also recorded with his side-project The Last Shadow Puppets and as a solo artist.

Raised in High Green, a suburb of Sheffield, South Yorkshire, Turner is the only child of two teachers. When he was sixteen, he and three friends formed Arctic Monkeys. Their debut album, Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not (2006), became the fastest-selling debut album in British history and is considered by Rolling Stone to be one of the greatest debut albums of all time.[1] The band's subsequent studio albums, Favourite Worst Nightmare (2007), Humbug (2009), Suck It and See (2011), AM (2013) and Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino (2018), have experimented with desert rock, indie pop, R&B, and lounge music. Arctic Monkeys headlined Glastonbury Festival in both 2007 and 2013, and performed during the 2012 London Summer Olympics opening ceremony.

Turner and Miles Kane have released two orchestral pop albums – The Age Of The Understatement (2008) and Everything You've Come To Expect (2016) – as the co-frontmen of The Last Shadow Puppets. Turner provided an acoustic soundtrack for the feature film Submarine (2010). He co-wrote and co-produced Alexandra Savior's debut album, Belladonna of Sadness (2017).

Turner's lyricism, ranging from kitchen sink realism to surrealist wordplay, has been widely praised. Each of his eight studio albums have reached number one on the UK Album Chart. He has won seven Brit Awards, an Ivor Novello Award, and has been nominated for the Mercury Prize five times, winning once.

Biography

Early life

Turner grew up in High Green, a suburb of Sheffield, South Yorkshire. He is an only child.[2] His parents, Penny and David Turner, both worked at local secondary schools; his mother was a German teacher while his father taught physics and music.[3] During car journeys, his mother introduced him to music by Led Zeppelin,[4] David Bowie,[5] Jackson Browne,[3] The Eagles,[6] The Carpenters,[7] Al Green,[8] The Beatles,[9] and The Beach Boys.[10] His father was a fan of jazz and swing music,[5] particularly Frank Sinatra.[9] He played the saxophone, trumpet and piano,[11] and had been a member of big bands.[7] Turner himself took piano lessons until he was eight years old.[11][12]

At the age of five, Turner met his classmate and neighbour Matt Helders, and they grew up together.[13][14] They met Andy Nicholson at secondary school[15] and the three friends bonded over their shared enjoyment of rap artists such as Dr. Dre,[16] Wu-Tang Clan,[6] Outkast,[6] and Roots Manuva.[6] They spent their weekends "making crap hip-hop" beats using Turner's father's Cubase system.[17][7] Turner and his friends became interested in guitar bands following the breakthrough of The Strokes in 2001.[18] That Christmas, when he was fifteen, Turner's parents bought him a guitar.[19]

Turner was educated at Stocksbridge High School (1997–2002).[20] He did not read regularly[21] and was too self-conscious to share his writing with others.[22] Nonetheless, he enjoyed English lessons.[23] His teacher, Simon Baker, later remembered him as a clever pupil who was "quite reserved ... a little bit different."[23] He noted that Turner had an "incredibly laid-back" approach to school work, which worried his mother.[23] Turner then spent two years at Barnsley College (2002–2004), where he studied for A-levels in music technology and media studies, and AS-levels in English, photography and psychology.[24]

2002–2004: Formation of Arctic Monkeys

After watching friends perform in local bands, Turner, Helders, Nicholson and another friend, Jamie Cook, decided to form Arctic Monkeys in mid-2002.[25] In the early days of the band, Helders has recalled that Turner "wasn’t necessarily going to be the singer" but was the obvious candidate for lyricist: "I knew he had a thing for words."[26] Before playing a live show, the band rehearsed for a year in both Turner and Helders' garages and, later, at an unused warehouse in Wath.[14] Turner gradually began to share lyrics with his bandmates.[27] According to Helders' mother, who drove the teenagers to and from their rehearsal space three times a week: "If they knew you were there, they would just stop so we had to sneak in."[14] Their first gig was on Friday, 13 June 2003, supporting The Sound at a local pub called The Grapes.[28] The set, which was partly recorded,[29] comprised both original songs and cover versions of songs by The Strokes, The Vines, The Beatles, The White Stripes, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Undertones, Fatboy Slim, and The Datsuns.[30][31]

In the summer of 2003, Turner played seven gigs in York and Liverpool as a rhythm guitarist for the funk band Judan Suki, after meeting the lead singer Jon McClure on a bus.[32][33] That August, while recording a demo with Judan Suki at Sheffield's 2fly Studios, Turner asked Alan Smyth if he would produce an Arctic Monkeys demo. Smyth obliged and "thought they definitely had something special going on. I told Alex off for singing in an American voice at that first session."[34] An introduction by Smyth led to the band acquiring a management team, Geoff Barradale and Ian McAndrew.[35] They paid for Arctic Monkeys to record numerous three-song demos in 2003 and 2004.[36] Barradale drove the band around venues in Scotland, the Midlands, and the north of England to establish their reputation as a live band.[15] They handed out copies of the demo CDs after each show and fans began sharing the unofficial Beneath the Boardwalk demo compilation online.[37] After finishing college in mid-2004, Turner deferred plans to attend university in Manchester.[7][38] He began working part-time as a bartender at the Sheffield music venue The Boardwalk. There, he met well-known figures including musician Richard Hawley and poet John Cooper Clarke.[39][40] By the end of 2004, Arctic Monkeys' audiences were beginning to sing along with their songs[41] and the demo of "I Bet You Look Good on The Dancefloor" was played on BBC Radio 1 by Zane Lowe.[42]

2005–2007: Rise to fame

Arctic Monkeys came to national attention in 2005. They received their first mention in a national newspaper in April, with a Daily Star reporter describing them as "the most exciting band to emerge this year".[43] They self-released an EP, featuring the single "Fake Tales of San Francisco", in May[44] and commenced their first nationwide tour soon afterwards.[45] Turner began dating London-based student Johanna Bennett around this time.[46] In June, in the midst of a bidding war, Arctic Monkeys signed to the independent label Domino Recording Company.[47] They recorded an album in rural Lincolnshire with producer Jim Abbiss.[47] In October, the single "I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor" debuted at number one on the UK Singles Chart.[48] In reviewing a sold-out show at the London Astoria, Alexia Loundras of The Independent noted that the nineteen-year-old Turner had a "commanding" stage presence, despite dressing like an "ordinary bloke" in "baggy jeans and T-shirt".[49]

Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not, Arctic Monkeys' debut album, was released in January 2006. Turner's lyrics, chronicling teenage nightlife in Sheffield, were widely praised.[50] Kelefa Sanneh of The New York Times remarked: "Mr. Turner's lyrics are worth waiting for and often worth memorizing, too ... He has an uncanny way of evoking Northern English youth culture while neither romanticizing it nor sneering at it."[51] Musically, Alexis Petridis of The Guardian noted that the album was influenced by guitar bands "from the past five years ... Thrillingly, their music doesn't sound apologetic for not knowing the intricacies of rock history."[52]

It was the fastest-selling debut album in British music history and quickly became a cultural phenomenon.[53] In interview profiles, Turner was described as quiet and uncomfortable with attention.[54] Less than two months after the album's release, he declared that Sheffield-inspired songwriting was "a closed book": "We're moving on and thinking about different things."[55] The band turned down many promotional opportunities[56] and quickly released new material - a five-track EP Who the Fuck Are Arctic Monkeys? in April, and a stand-alone single, "Leave Before the Lights Come On", in August. That summer, the band made the decision to permanently replace Nicholson, who had taken a touring break due to "fatigue", with Nick O'Malley, another childhood friend.[57][58] As of 2015, Turner and Nicholson remain "close friends".[59][60]

Arctic Monkeys' second album, Favourite Worst Nightmare, was released in April 2007. It was produced by James Ford in London.[61] Lyrically, the album touches on fame, love, and heartache.[62] Turner and Bennett had ended their relationship in January; she was credited as a co-writer on "Fluorescent Adolescent".[63][64] While uninterested in the songs concerning fame, Marc Hogan of Pitchfork said the album displayed Turner's "usual gift for vivid imagery" and explored "new emotional depth".[62] Petridis of The Guardian noted that the band were "pushing gently but confidently at the boundaries of their sound", with hints of "woozy psychedelia" and "piledriving metal".[65] The album was a commercial success.[66] Arctic Monkeys headlined Glastonbury Festival in the summer of 2007, with Rosie Swash of The Guardian remarking upon Turner's "steady, wry stage presence": "Arctic Monkeys don't do ad-libbing, they don't do crowd interaction, and they don't do encores."[67]

Turner began to collaborate with other artists in 2007. He worked with rapper Dizzee Rascal on the Arctic Monkeys B-side "Temptation", a version of which also featured on Rascal's album Maths and English.[68] They performed the song live at Glastonbury Festival.[67] Turner co-wrote three songs on Reverend and the Makers' debut album The State Of Things, after briefly sharing a Sheffield flat with the frontman Jon McClure.[69] Another Sheffield singer, Richard Hawley, featured on the Arctic Monkeys' B-side "Bad Woman" and performed with the band at the Manchester Apollo, as part of a concert film directed by Richard Ayoade.[70] Turner also announced plans to form a side-project band, The Last Shadow Puppets, with James Ford and Miles Kane, whom he had befriended in mid-2005.[71][72]

2008–2011: Musical experimentation

_006_(cropped).jpg)

The Last Shadow Puppets' debut album, The Age of the Understatement, was recorded in the Loire Valley, France[73] and was released in April 2008, shortly after Turner had moved from Sheffield to east London.[74][75] It was co-written by Turner and Kane, and featured string arrangements by Owen Pallett.[76] Alexa Chung, dating Turner since mid-2007,[77] featured in the music video for "My Mistakes Were Made For You".[78] Hogan of Pitchfork noted that, lyrically, Turner was "moving from his anthropologically detailed Arctics brushstrokes to bold, cinematic gestures."[79] Petridis of The Guardian detected "the audible enthusiasm of an artist broadening his scope".[80] During a tour with the London Philharmonic Orchestra,[81] The Last Shadow Puppets gave a surprise performance at Glastonbury Festival, with both Matt Helders and Jack White making guest appearances.[82] Alison Mosshart performed with the band at the Olympia in Paris, and provided vocals for a B-side.[83][84] Also in 2008, Turner formed a covers band with Dev Hynes for a one-off show in London[85] and recorded a spoken word track "A Choice of Three" for Helders' compilation album Late Night Tales.[86]

Turner has described Arctic Monkeys' third album, Humbug, released in August 2009, as "a massive turning point" in the band's career.[87] They travelled to Joshua Tree, California to work with producer Josh Homme of Queens of the Stone Age, and explored a heavier sound.[88] While Petridis of The Guardian found some lyrics "too oblique to connect", he was impressed by the band's "desire to progress". He described "Cornerstone" as a "dazzling display of what Turner can do: a fabulously witty, poignant evocation of lost love."[89] Joe Tangari of Pitchfork felt the album was a "legitimate expansion of the band's songwriting arsenal" and described "Cornerstone" as the highlight.[90] For Arctic Monkeys' fanbase, the album's change of direction initially proved divisive.[91] During a break in the UK Humbug tour, Turner joined Richard Hawley on stage at a London charity concert,[92] and played a seven-song acoustic set.[93] Homme joined Arctic Monkeys for a live performance in Pioneertown, California.[94]

While living in Brooklyn, New York, where he moved with Chung in the spring of 2009,[95] Turner wrote an acoustic soundtrack for the coming-of-age feature film Submarine (2010).[96] His friend, director Richard Ayoade, initially approached him to sing cover versions[97] but, instead, he recorded six original songs in London, accompanied by James Ford and Bill Ryder-Jones.[98][99] The Submarine EP was released in March 2011.[100] Paul Thompson of Pitchfork felt "Turner's keen wit and eye for detail" had created a "tender portrayal" of adolescent uncertainty.[101] Turner also co-wrote six songs for Miles Kane's debut solo album Colour of the Trap (2011) and co-wrote Kane's standalone single "First of My Kind" (2012).[102]

Turner wrote Arctic Monkeys' fourth album, Suck It and See, in New York[103] and met up with his bandmates and James Ford for recording sessions in Los Angeles. Turner and Chung had moved back to London by the time of the album's release in June 2011, and split soon after.[104] Marc Hogan of Pitchfork enjoyed the album's "chiming indie pop balladry" and "muscular glam-rock".[105] Petridis of The Guardian remarked that Turner's new lyrical style of "dense, Dylanesque wordplay is tough to get right. More often than not, he pulls it off. There are beautifully turned phrases and piercing observation."[106] Richard Hawley co-wrote and provided vocals for the B-side, "You and I", and performed the song with the band at the Olympia in Paris.[107] Turner joined Elvis Costello on stage in New York to sing "Lipstick Vogue".[108]

2012–2017: International success

By 2012, Arctic Monkeys were based in Los Angeles, with Turner and Helders sharing a house.[109] Arctic Monkeys toured the US as the support act for The Black Keys in early 2012. While they had previously opened for Oasis and Queens of the Stone Age at one-off shows, it was the band's first time to tour as a supporting act.[110] They released "R U Mine?" as a standalone single in preparation for the tour, with Turner's new girlfriend, Arielle Vandenberg, appearing in the music video. Faced with winning over indifferent audiences, Turner, now sporting a "rockabilly-inspired quiff", began to change his stage persona. Brian Hiatt of Rolling Stone noted of his "newfound showmanship": "He puts his guitar down to strut and dance, drops to his knees for solos when he does play, flirts shamelessly with the female fans."[4] Later that year, Arctic Monkeys performed "I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor" and a cover of "Come Together" by The Beatles at the 2012 London Summer Olympics opening ceremony. In early 2013, Turner provided backing vocals for the Queens of the Stone Age song "If I Had a Tail"[111] and played bass guitar on "Get Right", a Miles Kane B-side.[112] Arctic Monkeys headlined Glastonbury Festival for a second time in June.[113][114]

AM was released in September 2013.[115][116][117] Ryan Dombal of Pitchfork said that the album, dealing with "desperate 3 a.m. thoughts", managed to modernise "T. Rex bop, Bee Gees backup vocals, Rolling Stones R&B, and Black Sabbath monster riffage".[118] Phil Mongredien of The Guardian described it as "their most coherent, most satisfying album since their debut": "Turner proves he has not lost his knack for an insightful lyric."[119] Arctic Monkeys promoted the album heavily in the US, in contrast to previous album campaigns where, according to Helders, they had refused to do radio promotion: "We couldn’t even have told you why at the time. Just stubborn teenage thinking."[4] Arctic Monkeys spent 18 months touring AM; they were joined onstage by Josh Homme in both Los Angeles and Austin.[120][121] Turner briefly reunited with Chung in the summer of 2014, having ended his two-year relationship with Vandenberg earlier that year.[122][123][124]

Columbia Records approached Turner about working with Alexandra Savior in 2014, and he co-wrote her debut album, Belladonna of Sadness, in between Arctic Monkeys' touring commitments. Turner and James Ford co-produced the album in 2015.[125][126][127] An additional song "Risk" was recorded with T Bone Burnett for an episode of the crime drama True Detective.[128] While Turner and Savior performed together in Los Angeles in 2016,[129] the album was not released until April 2017. In reviewing it, Hilary Hughes of Pitchfork remarked: "Turner’s musical ticks are so distinct that they’re instantly recognizable when someone else tries to dress them up as their own."[130] Savior later said the press attention surrounding Turner's involvement was overwhelming: "I'm so grateful for him, but I'm also like, 'Alright, alright!'"[127]

The Last Shadow Puppets released their second album, Everything You've Come to Expect, in April 2016. Turner, Kane and Ford were joined by Zach Dawes of Mini Mansions, with whom Turner had collaborated on the song "Vertigo" in 2015.[131] According to Turner, the album featured "the most straight-up love letters" of his career, written for American model Taylor Bagley.[132] (They dated from early 2015 to mid-2018.)[133][134] Laura Snapes of Pitchfork detected an air of "misanthropy" in the album. However, she acknowledged that Turner was "no less a gifted lyricist than ever" and described some songs as "totally gorgeous ... the structures fluid and surprising".[135] Alexis Petridis of The Guardian enjoyed Turner’s "characteristically sparkling use of language" and "melodic skill". However, he felt the pair's "in-joking" during interviews and Kane's "leery" encounter with a female Spin journalist cast "an uncomfortable pall" over the album.[136] From March until August 2016, they toured in Europe and North America.[137] In December 2016, they released The Dream Synopsis, an EP which included covers of "Les Cactus" by Jacques Dutronc and "Is This What You Wanted" by Leonard Cohen.

2018 onward: Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino

Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino, Arctic Monkeys' sixth album, was released in May 2018.[138] After receiving a Steinway Vertegrand piano as a 30th birthday present from his manager, Turner wrote the space-themed album from the perspective of "a lounge-y character".[139][140] Having written "the most straight-up love letters" of his career on Everything You've Come to Expect, he felt ready to explore wider themes.[141] He recorded demos at home, and shared them with Cook in early 2017. Cook was initially taken-aback by the change in direction: "It took a few listens to even begin to, like… But I don’t think any of us wanted to make an AM, Part Two, so I were very, very excited by what he’d come up with."[142] By mid-2017, the whole band was recording the project, produced by Turner and James Ford, in both Los Angeles and France.[140] They were joined by a number of other musicians.[143]

Upon release, Jonah Weiner of Rolling Stone characterised Tranquility Base as "a captivatingly bizarre album about the role of entertainment – the desire to escape into it, and the desire to create it – during periods of societal upheaval and crisis."[142] Alexis Petridis of The Guardian found it "quietly impressive" that the band chose to release the "thrilling, smug, clever and oddly cold album" rather than more crowd-pleasing fare.[144] Jazz Monroe of Pitchfork declared it "a delirious and artful satire directed at the foundations of modern society."[145] The album became the eighth chart-topping album of Turner's career in the UK.[146] The band announced plans to tour the album from May to October 2018.[147] Turner began dating French singer Louise Verneuil in mid-2018.[148]

Artistry

Influences

Turner was "into hip-hop in a big way" as a teenager.[6] When he first started writing lyrics, Roots Manuva's Run Come Save Me was his main influence.[149][150] He also listened to Dr Dre,[150] Snoop Dogg,[151] OutKast, Eminem[6] and The Streets.[150][152] He has repeatedly cited Method Man as one of his favourite lyricists,[6][153][154] and has referenced the Wu-Tang Clan in his own lyrics.[155] The sound of 2013's AM was inspired by what Turner imagined "a hip-hop producer’s perspective would be",[156] and the songs incorporated lyrical structures used by Lil Wayne and Drake.[157][6] He is "a big fan" of the hip-hop producer and composer Adrian Younge,[158][159] and drew inspiration from his music when writing Tranquility Base Hotel and Casino.[160]

For Turner, The Strokes were "that one band that comes along when you are 14 or 15 years old that manages to hit you in just the right way and changes your whole perception of things."[161] He changed his style of dress and began to take an interest in guitar music.[162] He has since referenced the band in his lyrics.[162] The Vines were the first band Turner ever saw live and Craig Nicholls provided inspiration for his early stage persona.[163] Other early guitar influences included The Libertines,[164] The Coral[165] and The White Stripes.[166] In his late teens, Turner began "delving" into older music and discovered lyricists including Elvis Costello,[9] Ray Davies of The Kinks,[9][6] Jarvis Cocker of Pulp,[167] Paul Weller of The Jam,[168] and Morrissey of The Smiths.[169][170] Turner has since performed with Jack White of The White Stripes,[82] Costello[108] and Johnny Marr of The Smiths.[171]

John Cooper Clarke was "a massive inspiration" to Turner.[172] He was first introduced to Clarke's poetry at school.[23] Turner was working as a bartender at The Boardwalk in Sheffield in late 2004 when Clarke appeared on stage as the opening act for The Fall.[40] The performance made a big impression on the eighteen-year-old: "He's talking 100 miles an hour, and he's really funny ... It just blew my mind."[173] Turner was inspired by Clarke's use of a regional accent and the early Arctic Monkeys song "From the Ritz to the Rubble" was his homage to Clarke's style ("my best shot at it, at least").[174] Later in his career, Turner published a Clarke poem as part of a single's artwork[175] and used another as the lyrical basis for a song.[176]

By 2007, Turner was drawing influence from film scores and included an Ennio Morricone organ sample in the song "505".[177] He has since referenced scores composed by John Carpenter,[178] François de Roubaix,[179] Nino Rota, Jean-Claude Vannier and David Axelrod.[180] When forming The Last Shadow Puppets, Turner had just discovered Serge Gainsbourg's Histoire de Melody Nelson, The Electric Prunes's Mass in F Minor and the back catalogue of Scott Walker.[181] Listening to both Walker and Nina Simone inspired him to change his style of singing.[160] During the recording of Humbug, Josh Homme introduced Turner to music by Creedence Clearwater Revival,[182] Cream, Roky Erickson and Captain Beyond.[183] The structure of the song "Cornerstone" was inspired by Jake Thackray.[9][184]

Turner became interested in country music during the making of 2011's Suck It And See.[185] He admired the songcraft displayed by Townes Van Zandt,[6] Patsy Cline,[186] George Jones, Roger Miller, Willie Nelson,[187] Hank Williams and Johnny Cash.[188] He was also listening to Gene Clark[154] and Bob Dylan's Desire during this period.[189] During the making of AM, Turner drew from a wide variety of musical influences. He was listening to soul music by Al Green, Sam Cooke, Betty Davis and Dungeon Family, rock music by Harry Nilsson,[190] Fleetwood Mac, Captain Beefheart, The Rolling Stones, Black Sabbath, The Stooges[191][149] and folk music by Michael Chapman.[149][192]

When The Last Shadow Puppets reformed, Turner was listening to Isaac Hayes, Style Council, Ned Doheny[193] and Todd Rundgren.[194] He spoke of his admiration for Benji Hughes's A Love Extreme. Turner has described Leon Russell's "A Song for You" as "one of the greatest songs of all time".[195] He cited Russell's music as an influence when writing both AM and Tranquility Base Hotel and Casino.[149][196] Dion's Born to Be with You is one of Turner's favourite albums,[197] and he has mentioned the song "Only You Know" in many interviews.[33] He has taken inspiration from the production of Born to Be with You and The Beach Boys's Pet Sounds.[198]

Nick Lowe,[199] Nick Cave,[199] John Cale[150] and Lou Reed are among Turner's favourite lyricists.[200] He has covered Leonard Cohen's "Memories" and "Is This What You Wanted" with The Last Shadow Puppets.[201][202][203] The Beatles are an influence,[204] as is David Bowie.

Discography

Solo

- 2011 – Submarine

Arctic Monkeys

- 2006 – Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not

- 2007 – Favourite Worst Nightmare

- 2009 – Humbug

- 2011 – Suck It and See

- 2013 – AM

- 2018 – Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino

The Last Shadow Puppets

Collaborations

- 2007 – Reverend and The Makers – The State of Things (writer and vocalist on "The Machine", co-writer of "He Said He Loved Me" and "Armchair Detective")

- 2007 – Dizzee Rascal – Maths + English ("Temptation")

- 2008 – Matt Helders – Late Night Tales: Matt Helders ("A Choice of Three")

- 2011 – Miles Kane – Colour of the Trap (co-writer of "Rearrange", "Counting Down the Days", "Happenstance", "Telepathy", "Better Left Invisible" and "Colour of the Trap")

- 2012 – Miles Kane – First of My Kind EP (co-writer of "First of My Kind")

- 2013 – Miles Kane – Don't Forget Who You Are (co-writer and bassist on B-side "Get Right")

- 2013 – Queens of the Stone Age – ...Like Clockwork (guest vocalist on "If I Had a Tail")

- 2015 – Mini Mansions – The Great Pretenders (co-writer and guest vocalist on "Vertigo", co-writer on "Valet")

- 2015 – Alexandra Savior – True Detective season 2 original soundtrack (co-composed song "Risk" on guitar, keyboard, drums)[205][206][207]

- 2017 – Alexandra Savior – Belladonna of Sadness (co-writer, co-producer, bass, guitar, keyboards, and synthesizers)

References

- ↑ "100 Best Debut Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 22 March 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Sterdan, Darryl. "Monkeys Still Shining for Turner". Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- 1 2 Day, Elizabeth (26 October 2013). "Arctic Monkeys: 'In Mexico it was like Beatlemania'". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 Hiatt, Brian (21 October 2013). "How Arctic Monkeys Reinvented Their Sound". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Arctic Monkeys interview on Absolute Radio". Absolute Radio's Youtube. 7 November 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Dombal, Ryan (10 May 2012). "5–10–15–20: Alex Turner". Pitchfork. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Cameron, Keith (July 2007). "The Reluctant Genius of Alex Turner". Q. No. 252.

- ↑ Seban, Johanna (5 September 2013). "Alex Turner par Etienne Daho". Les Inrocks (in French). Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Matheny, Skip (12 March 2010). "Drinks With: Arctic Monkeys « American Songwriter". American Songwriter. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Rachel, T. Cole (31 May 2011). "Progress Report: Arctic Monkeys". Stereogum. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- 1 2 Divola, Barry (11 May 2018). "Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner on long-awaited album Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ Armitage, Simon (12 July 2009). "Highly evolved". The Observer. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Halo, Martin (30 May 2007). "Interview: Arctic Monkeys 'Setting Fire to the Dancefloor' | TheWaster.com". www.thewaster.com. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Jill Helders: Arctic Mummy". BBC Yorkshire. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- 1 2 McLean, Craig (1 January 2006). "Craig McLean spends three months on the road with the Arctic Monkeys". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Murphy, Lauren (5 September 2013). "Arctic Monkeys get funky on album number five". The Irish Times. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Hanging Out With Andy Nicholson: Ex-Arctic Monkey, Producer & Photographer". Orbiter Lover. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Hilburn, Robert (2 April 2006). "Welcome to the jungle". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Caesar, Ed (14 April 2007). "Alex Turner: That's what he's not. So what is he?". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Coleman, Mark (12 September 2008). "What were today's celebrities like as children?". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Button, James (15 April 2007). "Back for Seconds". The Age. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Martin, Rick (5 April 2011). "Arctic Monkeys: Read Their First Ever NME Feature - NME". NME. Retrieved 25 May 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogers, Jude (25 April 2010). "Schoolteachers of Rock". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Shimmon, Katie (29 November 2005). "College days". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ↑ Simpson, Dave (2 February 2018). "Made of steel: how South Yorkshire became the British indie heartland". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Murison, Krissi (20 May 2018). "Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner on their new album and returning to the limelight". Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Odell, Michael (15 August 2009). "Monkey business". The National. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ McLean, Craig (21 November 2009). "Arctic Monkeys hit their stride". The Times. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "The real story about the Arctic Monkeys first ever gig at The Grapes in Sheffield. – Reyt Good Magazine". www.rgm.press. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys, Geese Confession, Job Interview Hacks, Jo Whiley & Simon Mayo - BBC Radio 2". BBC. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ Connick, Tom (13 June 2018). "15 years on, the story of Arctic Monkeys' first ever gig - NME". NME. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Beaumont, Mark (8 May 2018). "Arctic Monkeys talk to NME in 2007 about 'Favourite Worst Nightmare'". NME. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- 1 2 Stokes, Paul. "Alex Turner". Q Magazine (November 2011). p. 63.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Lynskey, Dorian (May 2006). "The Lads Are Alright". Blender.

- ↑ Saunders, Chris. "Alan Smyth". Counterfeit Magazine. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Monkey business: Ian McAndrew on 25 years of Wildlife Entertainment - Music Business Worldwide". Music Business Worldwide. 31 July 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Lanham, Tom (2 April 2006). "Monkey business". SFGate. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "Go Nuts with the Monkeys". Manchester Evening News. 29 August 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Creighton, Keith (21 August 2012). "Richard Hawley Aims His Guitar At The 1 Percent". Popdose. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- 1 2 Fitzmaurice, Larry (19 September 2013). "Interviews: Arctic Monkeys". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Hasted, Nick (16 December 2005). "Year of the Arctic Monkeys". The Independent. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Webb, Rob (4 February 2005). "Too much Monkey business?". BBC South Yorkshire. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Insiders' guide to Arctic Monkeys". BBC. 23 April 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Webb, Rob (25 May 2005). "Single Review: Arctic Monkeys - Five Minutes With Arctic Monkeys". DrownedInSound. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ "Hey, hey it's the Monkeys!". BBC Yorkshire. 2005. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Davis, Ben (18 May 2010). "Thorney girl living the rock star life with Kings of Leon boyfriend – Latest Local News". Peterborough Evening Telegraph. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- 1 2 Muir, Ava (21 June 2018). "Arctic Monkeys' Career So Far: From Rubble to the Ritz". Exclaim!. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Barton, Laura (25 October 2005). "The question: Have the Arctic Monkeys changed the music business?". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Loundras, Alexia (11 October 2005). "Arctic Monkeys, Astoria, London". The Independent. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Sullivan, Caroline (27 January 2006). "Caroline Sullivan: Whatever they say they are, that's what they are". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Sanneh, Kelefa (January 30, 2006). "Teen Spirit: Arctic Monkeys Observed in the Wild". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Petridis, Alexis (13 January 2006). "CD: Arctic Monkeys, Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ Cromelin, Richard (15 March 2006). "Arctic Monkeys play it cool". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Petridis, Alexis (15 April 2006). "Weekend: The Arctic Monkeys in New York". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ↑ Bendersky, Ari (1 March 2006). "Monkeys of the Arctic Kind". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Sinclair, David (26 May 2006). "Arctic Monkeys: Too much monkey business". The Independent. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys bass player quits". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 June 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Raihala, Ross (5 May 2007). "Better late than never for Arctic Monkeys' bassist". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ "Hanging Out With Andy Nicholson: Ex-Arctic Monkey, Producer & Photographer". Orbiter Lover. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ "Andy Nicholson 'always open' to working with former Arctic Monkeys bandmates on new label - NME". NME. 23 July 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ Robinson, John (23 April 2007). "Alex Turner Q & A - Uncut". Uncut. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- 1 2 Hogan, Marc (24 April 2007). "Arctic Monkeys: Favourite Worst Nightmare Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ↑ "ARCTIC HEARTACHE". The Mirror. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Hodgson, Jaimie (15 July 2007). "Ex-girlfriend helps Arctic Monkeys to a hit". The Observer. London: Guardian News and Media. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ↑ Petridis, Alexis (20 April 2007). "CD: Arctic Monkeys, Favourite Worst Nightmare". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ Swash, Rosie (25 April 2007). "Arctic Monkeys outselling the rest of the top 20 combined". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- 1 2 Swash, Rosie (23 June 2007). "Review: Arctic Monkeys, Pyramid stage, Friday 11.05pm". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ Thompson, Ben (21 April 2007). "Ben Thompson speaks frankly to Dizzie Rascal". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ Youngs, Ian (9 October 2007). "Reverend preaches the power of pop". BBC. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ "Interview: Richard Hawley". BBC South Yorkshire. 25 November 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Muir, Ava (21 June 2018). "Arctic Monkeys' Career So Far: From Rubble to the Ritz". Exclaim!. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Fletcher, Alex (2 August 2007). "Arctic Monkey plans side project". Digital Spy. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Hermann, Andy (28 March 2016). "The Last Shadow Puppets Joke Around About Everything, Except Their Music". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ Cobb, Ben (7 June 2017). "Alex Turner". AnotherMan. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ "Reverend and The Makers' Jon McClure gets it all off his chest". The Mirror. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ Thompson, Ben (16 March 2008). "What do you get when you mix one Arctic Monkey and one young Rascal, asks Ben Thompson". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ "When Alex met Alexa: Arctic Monkeys singer hand-in-hand with Channel 4". Evening Standard. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Knight, David (26 February 2009). "Richard Ayoade wins best video and best DVD at NME Awards on Promo News". PromoNews.tv. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ Hogan, Marc. "The Last Shadow Puppets: The Age of the Understatement Album Review | Pitchfork". Pitchfork. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Petridis, Alexis (17 April 2008). "CD of the week: The Last Shadow Puppets, The Age of the Understatement". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ Green, Thomas H. (19 August 2008). "The Last Shadow Puppets review: satisfied relief". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- 1 2 "Last Shadow Puppets and Jack White play secret Glastonbury gig - NME". NME. 28 June 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ↑ Thompson, Paul. "Last Shadow Puppets Enlist Kills' Mosshart for EP | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Kills discuss Arctic Monkeys collaboration - NME". NME. 12 August 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ Duff, Oliver (1 February 2008). "How all hell broke loose when two indie icons celebrated their past". The Independent. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ Michaels, Sean (5 September 2008). "Alex Turner to make spoken-word debut". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys Q&A". The Daily Telegraph. 27 November 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkey Alex Turner gives Uncut the lowdown on new LP!". Uncut. 3 August 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Petridis, Alexis (20 August 2009). "Arctic Monkeys: Humbug | CD review". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys: Humbug Album Review | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ McBain, Hamish (9 May 2018). "Dive back in Arctic Monkeys' divisive 'Humbug' from this 2009 interview". NME. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ↑ Davies, Rodrigo (20 November 2009). "Hawley joined by Monkey on stage". BBC News. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ Empire, Kitty (22 November 2009). "Richard Hawley, Alex Turner and I Blame Coco | Pop reviews". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "Alex Turner: 'If I could play guitar like Josh Homme, I f**king would'". www.gigwise.com. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ Ellen, Barbara (28 May 2011). "Arctic Monkeys: 'We want to get better rather than get bigger'". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Periscope up: Richard Ayoade and Alex Turner unite their talents in". The Independent. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Alex Turner: GQ Music Issue 2011: The Survivors". GQ. 15 November 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Bill Ryder Jones – Interview". Part Time Wizards. Archived from the original on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Bill-Ryder Jones – former The Coral guitarist and solo artist". Your Move Magazine. 2 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Alex Turner - Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. 26 March 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ "Alex Turner: Submarine OST Album Review | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "First Of My Kind / Miles Kane". ASCAP. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Norris, John (31 May 2011). "Craft Service: Arctic Monkeys Branch Out - Interview Magazine". Interview Magazine. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ Nicholl, Katie (1 August 2011). "No more Monkeying around for Alexa Chung as she splits with Arctic frontman Alex Turner". Daily Mail. London.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys: Suck It and See Album Review". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ Petridis, Alexis (2 June 2011). "Arctic Monkeys: Suck It and See – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Check Out: Arctic Monkeys feat. Richard Hawley "You & I"". Consequence of Sound. 20 January 2012.

- 1 2 Friedman, Roger (24 May 2011). "Elvis Costello Spins a Wheel of Fortune, Diana Krall Dances". Showbiz411. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys go California". The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ "Q&a Arctic Monkeys' Matt Helders - On touring the US with The Black Keys, life as a support band, getting love from Metallica & new album plans". Q Magazine. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Kalopsia by Queens of the Stone Age". Songfacts.com. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ "Miles Kane – Don't Forget Who You Are (Vinyl)". Discogs. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ Beaumont, Mark (29 June 2013). "Arctic Monkeys at Glastonbury 2013 – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Savage, Mark (29 June 2013). "Arctic Monkeys headline Glastonbury". BBC News. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner on "AM," Working with Josh Homme, and Adapting John Cooper Clarke". www.undertheradarmag.com. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner: 'I want to start writing follow-up to 'Suck It And See'". NME. 9 March 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ↑ Dunning, JJ (September 2013). "Arctic Monkeys are all over the place". The Fly.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys: AM Album Review | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Mongredien, Phil (7 September 2013). "Arctic Monkeys: AM – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Cubarrubia, RJ (4 October 2013). "Josh Homme Joins Arctic Monkeys Onstage". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ Webb, Jacob (13 October 2013). "Live Review: Austin City Limits 2013, Friday". The KEXP Blog. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20151001005204/http://www.asos.com/women/fashion-news/2014_07_7-mon/alexa-chung-alex-turner-meet-in-new-york/

- ↑ "Mark Shand will be played by Joseph Fiennes in a film about his life – Daily Mail Online". Mail Online. London. 7 June 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Strang, Fay (30 July 2014). "Alexa Chung wears T-shirt featuring ex-boyfriend Alex Turner's band name – Daily Mail Online". Mail Online. London. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ http://www.coupdemainmagazine.com/alexandra-savior/11541. Retrieved 16 July 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Alexandra Savior On Songwriting, Working With Alex Turner & Visiting Australia - Music Feeds". Music Feeds. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- 1 2 Graves, Shahlin (10 October 2016). "Interview: Alexandra Savior on her upcoming debut album". Coup De Main Magazine. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ↑ "Meet Alexandra Savior: The LA Songwriter Who's Made An Entire Album With Alex Turner". NME. 16 May 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ https://www.nme.com/blogs/nme-radar/meet-alex-turners-new-muse-alexandra-savior-8134. Retrieved 16 July 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Alexandra Savior: Belladonna of Sadness Album Review | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ↑ Renshaw, David (10 March 2015). "Mini Mansions song with Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner released online". NME. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ MOJO June 2018, page 79, Andrew Cottirill

- ↑ Distefano, Alex (28 June 2018). "R.I.P. Steve Soto of The Adolescents, Manic Hispanic". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ↑ Boyle, Simon (18 September 2018). "Arctic Monkeys frontman Alex has split from US model girlfriend Taylor Bagley". The Sun. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ "The Last Shadow Puppets: Everything You've Come to Expect Album Review | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ↑ Petridis, Alexis (24 March 2016). "The Last Shadow Puppets: Everything You've Come to Expect review – more a smirking in-joke than a band". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ↑ "The Last Shadow Puppets - The Dream Synopsis EP". The Last Shadow Puppets - Everything You've Come To Expect. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ Trendell, Andrew (5 April 2018). "Arctic Monkeys announce new album 'Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino'". NME. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ↑ Newstead, Al (11 May 2018). "Alex Turner unpacks Arctic Monkeys' subversive, sci-fi referencing new album". triple j. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- 1 2 https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/rock/8357304/inside-arctic-monkeys-tranquility-base-hotel-casino-alex-turner-interview

- ↑ MOJO June 2018, page 79, Andrew Cottirill

- 1 2 Weiner, Jonah (3 May 2018). "Arctic Monkeys Start Over: Inside Their Weird New Sci-Fi Opus". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "NME Big Read: Arctic Monkeys 'from the Ritz to the Hubble'". NME. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ↑ Petridis, Alexis (10 May 2018). "Arctic Monkeys: Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino review – funny, fresh and a little smug | Alexis Petridis' album of the week". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys: Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino Album Review | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys set new chart record with massive sales as 'Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino' tops UK album chart - NME". NME. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ↑ https://www.nme.com/news/music/arctic-monkeys-first-2018-tour-date-announced-theyre-teasing-2218077. Retrieved 15 July 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Boyle, Simon (20 September 2018). "Alex Turner's new girlfriend Louise Verneuil looks just like ex Alexa Chung". The Sun. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Murphy, Lauren (6 September 2013). "Arctic Monkeys get funky on album number five". The Irish Times. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Bevan, David (10 September 2013). "The SPIN Interview: Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner". Spin. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ "Believe the hype: Arctic Monkeys rock". TODAY.com. 23 February 2006. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Taylor, Chris (2 April 2006). "Arctic Monkeys Formed By Hip-Hop Love". www.gigwise.com. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ https://www.spin.com/2013/09/arctic-monkeys-alex-turner-interview-am-album/. Retrieved 13 August 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Ryzik, Melena (13 May 2011). "Alex Turner on Arctic Monkeys' 'Suck It and See'". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Hyden, Steven (10 May 2018). "Arctic Monkeys Grow Up and Get Weird On Their Inspired New Album". UPROXX. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Marchand, Francois (29 November 2013). "Arctic Monkeys make a vintage leap (with video)". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Goodwyn, Tom (20 April 2012). "Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner: 'R U Mine?' references Drake and Lil Wayne' - NME". NME. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Healy, Pat (2 January 2014). "Arctic Monkeys are alive and kicking out the jams with 'AM'". Metro US. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Seban, Johanna (5 September 2013). "Alex Turner par Etienne Daho". Les Inrocks (in French). Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- 1 2 Beauvallet, JD (13 June 2018). ""No tengo Twitter ni Instagram, incluyo todas mis observaciones en mis canciones"". Los Inrockuptibles. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Cole, Rachel T. (31 May 2011). "Progress Report: Arctic Monkeys". Stereogum. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- 1 2 Smith, Thomas (25 July 2018). "Alex Turner loves The Strokes even more than you do – here's how a certain bromance unfolded - NME". NME. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ McLean, Craig (5 March 2006). "Stop making sense". The Observer.

- ↑ Gordon, Scott (22 May 2007). "Random Rules: Alex Turner of Arctic Monkeys". AV Club. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Coral speak about hero worship from Arctic Monkeys - NME". NME. 30 July 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Trendell, Andrew (2 August 2018). "Here's Arctic Monkeys covering The White Stripes in Detroit last night - NME". NME. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys diss 'annoying' Kaiser Chiefs - NME". NME. 27 October 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ Harris, John (24 June 2005). "John Harris asks why pop lyrics are in such decline". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ "Alex Turner - The Record(s) That Changed My Life - NME". NME. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ Fennessey, Sean (15 November 2011). "Alex Turner: GQ Music Issue 2011: The Survivors". GQ. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ "'He can't destroy history': Johnny Marr on veganism, Man City and Morrissey's legacy". The Guardian. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ Fink, Matt (8 November 2013). "Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner on "AM," Working with Josh Homme, and Adapting John Cooper Clarke". www.undertheradarmag.com. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ Bevan, David (10 September 2013). "The SPIN Interview: Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner". Spin. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Evidently... John Cooper Clarke". BBC Four. 15 December 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys collaborate with punk legend - NME". NME. 6 July 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ Hall, Duncan (18 April 2014). "Punk poet John Cooper Clarke talks art, Arctic Monkeys and the possibility of an autobiography". The Argus. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ "What's that sound? Arctic Monkeys sampling Ennio Morricone, 2007". Far Out Magazine. 23 February 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ Bassett, Jordan (6 May 2016). "What Is Alex Turner Listening To – And What Does It Tell Us About Him?". NME. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ↑ Roche, Jason (16 August 2018). "British Indie Band Arctic Monkeys Return With Tranquility". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ Moore, Sam (2 May 2018). "Alex Turner's 'Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino' playlist is an education in obscure music - NME". NME. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ The Last Shadow Puppets Yahoo Music Interview. 31 March 2016 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys : Desert Storm ? (1/2)". VoxPop (in French). Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ↑ Diver, Mike (August 2009). "Clash Speaks To Arctic Monkeys". Clash Magazine. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ↑ Turner, Jonno (24 January 2014). "Jake Thackray: Songwriter, Comedian, Yorkshireman". Sabotage Times. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Cronin, Seanna (11 November 2011). "Monkeys real party animals". CQ News. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ Coplan, Chris (13 January 2012). "Check Out: Alex Turner covers Patsy Cline's "Strange"". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ Sweeney, Eamon (27 May 2011). "Monkey business - Independent.ie". The Irish Independent. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ "Arctic Monkeys - Alex Turner's Guide To 'Suck It And See' - NME". NME. 26 April 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ Clayton-Lea, Tony (24 May 2011). "Dylan & Me". The Irish Times. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Dunning, JJ. "Arctic Monkeys". The Fly (September 2013). p. 28. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ Mafrouche, Thomas (September 2013). "Nocturne sur Mesure". Plugged. p. 30.

- ↑ Barker, Emily (13 May 2014). "101 Albums To Hear Before You Die - NME". NME. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ Oliver, Will (6 April 2016). "Interview: The Last Shadow Puppets - We All Want Someone To Shout For at We All Want Someone To Shout For". weallwantsomeone.org. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Last Shadow Puppets". Domino. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ↑ Brown, Lane (10 August 2018). "How to Write a Great Rock Lyric". Vulture. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ "PLAYLIST: Alex Turner Lists More Influences On New Album". Radio X. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ Stolworthy, Jacob (26 April 2018). "Alex Turner lists the songs that inspired the new Arctic Monkeys album". The Independent. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ Havens, Lyndsey (20 April 2018). "Inside Arctic Monkeys' New Album: Alex Turner Discusses Why Swapping Guitar for Piano Led to the Band's Most Ambitious Album". Billboard. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- 1 2 Orellana, Patricio (26 March 2012). "Alex Turner: "Creo que las cosas eran más cool en el pasado" - Rolling Stone Argentina". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ Kelly, Emma (31 October 2013). "'I'll make techno tunes for a laugh' Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner on their musical future". The Daily Star. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Pareles, Jon (31 October 2008). "Alex Turner and Miles Kane Play Orchestral Pop, the Way It Was (More or Less), at the Grand Ballroom". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ Breihan, Tom (17 October 2016). "The Last Shadow Puppets – "Is This What You Wanted" (Leonard Cohen Cover) Video". Stereogum. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "Alex Turner, Arctic Monkeys back with new 'dos". The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ "Liam Gallagher, Alex Turner, Paul Weller And More On The True Genius Of John Lennon - NME". NME. 8 October 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ "Alexandra Savior - Risk". AllMusic. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "HBO Shop". HBO. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "True Detective: Music from the HBO Series". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alex Turner. |