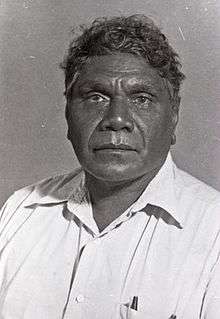

Albert Namatjira

| Albert Namatjira | |

|---|---|

Albert Namatjira, c. 1950 | |

| Born |

Elea Namatjira 28 July 1902 Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission, near Alice Springs |

| Died |

8 August 1959 (aged 57) near Alice Springs, Northern Territory |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Known for | Watercolour painting, Contemporary Indigenous Australian art |

| Spouse(s) | Rubina |

| Awards | Queen's Coronation Medal |

Albert Namatjira (28 July 1902 – 8 August 1959), born Elea Namatjira, was a Western Arrernte-speaking Aboriginal artist from the MacDonnell Ranges in Central Australia. As a pioneer of contemporary Indigenous Australian art, he was the most famous Indigenous Australian of his generation.

Born and raised at the Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission outside Alice Springs, Namatjira showed interest in art from an early age, but it was not until 1934 (aged 32), under the tutelage of Rex Battarbee, that he began to paint seriously.[1] Namatjira's richly detailed, Western art-influenced watercolours of the outback departed significantly from the abstract designs and symbols of traditional Aboriginal art, and inspired the Hermannsburg School of painting. He became a household name in Australia and reproductions of his works hung in many homes throughout the nation. As the first prominent Aboriginal artist to work in a western idiom, at the time he was widely regarded as representative of successful assimilation policies.

Namatjira was the first Northern Territory Aboriginal person to be freed from restrictions that made Aboriginal people wards of the State. In 1957, he became the first Aboriginal person to be granted restricted Australian citizenship,[2] which allowed him to vote, have limited land rights and buy alcohol. In 1956 his portrait, by William Dargie, became the first of an Aboriginal person to win the Archibald Prize.[3] Namatjira was also awarded the Queen's Coronation Medal in 1953, and was honoured with an Australian postage stamp in 1968.

Early life

Born at Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission, near Alice Springs in 1902,[4] Namatjira was raised on the Hermannsburg Mission and baptised after his parents' adoption of Christianity. He was born as Elea, but once baptised, they changed his name to Albert. After a western-style upbringing on the mission, at the age of 13 Namatjira returned to the bush for initiation and was exposed to traditional culture as a member of the Arrernte community (in which he was to eventually become an elder). He developed the love and respect of his land that is seen in his works. After he returned, he married his wife Rubina at the age of 18. His wife, like his father's wife, was from the wrong skin group and he violated the law of his people by marrying outside the classificatory kinship system. In 1928 he was ostracised for several years in which he worked as a camel driver and saw much of Central Australia, which he was later to depict in his paintings.

Having done a small amount of rough artwork in his youth, Namatjira was introduced to western-style painting through an exhibition by two painters from Melbourne at his mission in 1934. One of these painters, Rex Battarbee, returned to the area in the winter of 1936 to paint the landscape and Namatjira acted as a guide to show him local scenic areas. In return Namatjira was shown how to paint with watercolours, a skill at which he quickly excelled.

The height of success

Namatjira started painting in a unique style. His landscapes normally highlighted both the rugged geological features of the land in the background, and the distinctive Australian flora in the foreground with very old, stately and majestic white gum trees surrounded by twisted scrub. His work had a high quality of illumination showing the gashes of the land and the twists in the trees. His colours were similar to the ochres that his ancestors had used to depict the same landscape, but his style was appreciated by Europeans because it met the aesthetics of western art.

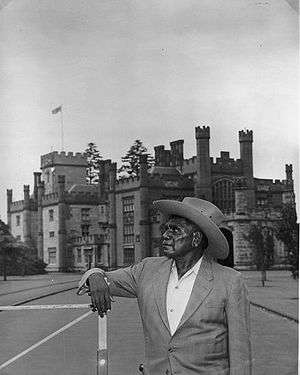

In 1938 his first exhibition was held in Melbourne. Subsequent exhibitions in Sydney and Adelaide also sold out. For ten years Namatjira continued to paint, his works continuing to sell quickly and his popularity continuing to rise. Queen Elizabeth II became one of his more notable fans and he was awarded the Queen's Coronation Medal in 1953 and met her in Canberra in 1954. Not only did his own art become widely recognized, but a painting of him by William Dargie won the Archibald Prize in 1956.[5] He became popular, critically acclaimed and wealthy. However, he was always glad to return to the outback.

Artworks

Namatjira's artworks were colourful and varied depictions of the Australian landscape. One of his first landscapes from 1936, Central Australian Landscape, shows a land of rolling green hills. Another early work, Ajantzi Waterhole (1937), shows a close up view of a small waterhole, with Namatjira capturing the reflection in the water. The landscape becomes one of contrasting colours, a device that is often used by Western painters, with red hills and green trees in Red Bluff (1938). Central Australian Gorge (1940) shows detailed rendering of rocks and reflections in the water. In Flowering Shrubs Namatjira contrasts the blossoming flowers in the foreground with the more barren desert and cliffs in the background. Namatjira's love of trees was often described so that his paintings of trees were more portraits than landscapes, which is shown in the portrait of the often depicted ghost gum in Ghost Gum Glen Helen (c.1945-49). Namatjira's skills at colouring trees can be clearly seen in this portrait.

Namatjira was fully aware of his own talent, as was shown when he was describing another landscape painter to William Dargie.

"He does not know how to make the side of a tree which is in the light look the same colour as the side of the tree in shadow...I know how to do better."

Namatjira's skills kept increasing with experience as is shown in the highly photographic quality of Mt Hermannsburg (1957), painted only two years before he died.

Later life

Due to his wealth, Namatjira soon found himself the subject of humbugging, a ritualised form of begging. Arrernte are expected to share everything they own, and as Namatjira's income grew, so did his extended family. At one time he was singlehandedly providing for over 600 people. To ease the burden on his strained resources, Namatjira sought to lease a cattle station to benefit his extended family. Originally granted, the lease was subsequently rejected because the land was part of a returned servicemen's ballot, and also because he had no ancestral claim on the property. He then tried to build a house in Alice Springs, but was cheated in his land dealings. The land he was sold was on a flood plain and was unsuitable for building. The Minister for Territories, Paul Hasluck, offered him free land in a reserve on the outskirts of Alice Springs, but this was rejected, and Namatjira and his family took up residence in a squalid shanty at Morris Soak—a dry creek bed some distance from Alice Springs. Despite the fact that he was held as one of Australia's greatest artists, Namatjira was living in poverty. His plight became a media cause célèbre, resulting in a wave of public outrage.

In 1957 the government exempted Namatjira and his wife from the restrictive legislation that applied to Aborigines in the Northern Territory. This entitled them to vote, own land, build a house and buy alcohol.[1] Although Albert and Rubina were legally allowed to drink alcohol, his Aboriginal family and friends were not. The nomadic Arrernte culture expected him to share everything he owned, even after they ceased being nomads. It was this contradiction that was to bring Namatjira into conflict with the law.[1]

When an Aboriginal woman, Fay Iowa, was killed at Morris Soak, Namatjira was held responsible by Jim Lemaire, the Stipendiary Magistrate, for bringing alcohol into the camp. He was reprimanded at the coronial inquest. It was then against the law to supply alcohol to an Aboriginal person. Namatjira was charged with leaving a bottle of rum in a place, i.e. on a car seat, where a clan brother and fellow Hermannsburg artist Henoch Raberaba, could get access to it. He was sentenced to six months in prison for supplying an Aboriginal with liquor. After a public uproar, Hasluck intervened and the sentence was served at Papunya Native Reserve. He was released after only serving two months due to medical and humanitarian reasons.

Despondent after his incarceration, Namatjira continued to live with Rubina in a cottage at Papunya, where he suffered a heart attack. There is evidence that Albert believed that he had the bone pointed at him by a member of Fay Iowa's family. The idea of being "sung" to death was also held by Frank Clune, a popular travel writer, aboriginal activist, and organiser of Albert's whirlwind 1956 trip.

After being transferred to Alice Springs hospital, Namatjira astonished his mentor Rex Battarbee by presenting him with three landscapes, with a promise of more to come; a promise unrealised. He died soon after of heart disease complicated by pneumonia on 8 August 1959 in Alice Springs.

Legacy

At the time of his death Namatjira had painted a total of around two thousand paintings.[6][7][8] His unique style of painting, however, was denounced soon after his death by some critics as being a product of his assimilation into western culture, rather than his own connection to his subject matter or his natural style.[9][7] This view has been largely abandoned and Albert Namatjira is hailed as one of the greatest Australian artists and a pioneer for Aboriginal rights.[10][11][12][13]

Namatjira's work is on public display in some of Australia's major art galleries, with some noteworthy exceptions. The Art Gallery of New South Wales now displays a number of Namatjira's work,[14] but initially rejected his work. In the words of Hal Missingham, then Director of the gallery: "We'll consider his work when it comes up to scratch".[15]

A number of biographical films have been made about Namatjira, including the 1947 documentary Namatjira the Painter.[16][17]

Two years before his death, part of Namatjira's copyright was sold to a company in exchange for royalties. After his death, Albert Namatjira's copyright was sold by the public trustee in 1983 for $8,500, despite Namatjira's will leaving his copyright to his widow and children.[18] The copyright was returned to the family's Albert Namatjira Trust in an October 2017 deal enabled by a donation by philanthropist Dick Smith, in the name of art dealer John Brackenreg, who was seen as having acquired the rights to Namatjira's art in 1957 in an act of exploitation.[19]

Namatjira has been the subject of numerous songs. Country star Slim Dusty was the first artist to record a tribute song, "Namatjira", in the 1960s, and Rick and Thel Carey followed up with their tribute "The Stairs That Namatjira Climbed" in 1963. Other tributes include John Williamson's "Raining on the Rock" from his 1986 album Mallee Boy and "The Camel Boy" from Chandelier Of Stars (2005); "Albert Namatjira" by the Australian band Not Drowning, Waving, featured on their 1993 album, Circus, and Midnight Oil's song "Truganini" of the same year; the famous patriotic song "I Am Australian"; Archie Roach's song, "Native Born"; and the reconciliation song, "Namatjira", written by Geoff Drummond and included on the politically activist album, The Chess Set released by Pat Drummond in 2004.[20]

In 1968 Namatjira was honoured on a postage stamp issued by Australia Post[21] and again in 1993 with examples of his work.[22][23]

The Namatjira Project was a community cultural development project launched in 2009 that included an award-winning theatre production by Big hART focusing on Namatjira's life and work.[24][25]

The Northern Territory electoral division of Namatjira, which surrounds Alice Springs, was renamed in 2012 from MacDonnell, in honour of Namatjira.[26]

In January 2013, two gum trees that featured prominently in Namatjira's watercolours were destroyed in an arson attack. The trees were in the process of being heritage-listed. Art writer Susan McCulloch called the attack an "appalling and a tragic act of cultural vandalism".[27]

A number of Albert Namatjira's descendants paint at the Iltja Ntjarra - Many Hands art centre in Alice Springs.[28][29]

1st Kingston Sea Scouts, in Tasmania, has an 18ft wooden hulled patrol boat named "Namatjira".

On 28 July 2017, Google commemorated Namatjira's 115th birthday with a featured Doodle for Australian users, acknowledging his substantial contributions to the art and culture of Australia.[30]

References

- 1 2 3 "Albert Namatjira". AGNSW collection record. Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- ↑ Namatjira profile, artistsfootsteps.com; accessed 26 July 2015.

- ↑ Kleinert, Sylvia. "Namatjira, Albert (Elea) (1902–1959)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ "Archibald Prize". AGNSW prize record. Art Gallery of New South Wales. 1956. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ↑ Grishin, Sasha (20 July 2017). "Albert Namatjira paintings donated to National Gallery of Australia". Canberra Times. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- 1 2 "Albert Namatjira: Bridging the Divide – The 8 Percent". the8percent.com. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Behrendt, Larissa; Fraser, Malcolm (2013). Indigenous australia for dummies. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118308431. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Kleinert, Sylvia. "Namatjira, Albert (Elea) (1902–1959)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Albert Namatjira - Australia's most famous aboriginal artist". Iltja Ntjarra. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "ALBERT NAMATJIRA". www.abc.net.au. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Albert Namatjira & the Hermannsburg School - Japingka Aboriginal Art Gallery". Japingka Aboriginal Art Gallery. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ National Gallery of Australia. "Seeing the centre". nga.gov.au. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Albert Namatjira :: The Collection :: Art Gallery NSW". www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Australia: From the Royal Academy to the Outback". www.winsornewton.com. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ ""HERALD" WEEK-END MAGAZINE Filming the life of Australia's famous aboriginal artist — Suggestion for approaching Mr. Chifley with a low bow — The wreek of the malabar, Easter 1931". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 29 March 1947. p. 10. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Albert Namatjira's family screens documentary highlighting copyright plight". ABC News. 23 October 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "'It was a mistake': official who sold Albert Namatjira's copyright". ABC News. 9 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ↑ Isabel Dayman (15 October 2017). "Albert Namatjira's family regains copyright of his artwork after Dick Smith intervenes". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ↑ "Pat Drummond Releases".

- ↑ Stamp of Albert Namatjira. 5c Stamp. www.australianstamp.com. Retrieved 6 January 2013

- ↑ Albert Namatjira "Ghost Gum". 45c, 1993 Stamp: www.australianstamp.com. Retrieved 6 January 2013

- ↑ Albert Namatjira "Across the plain to Mount Giles". 45c, 1993 Stamp: www.australianstamp.com. Retrieved 6 January 2013

- ↑ "Big hART Namatjira Project". www.namatjira.bighart.org. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "The skill of Namatjira's grandson - Arts - Entertainment - smh.com.au". www.smh.com.au. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Namatjira - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". ABC News. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Mercer, Phil (4 January 2013). "Australia ghost gum trees in Alice Springs 'arson attack'", BBC News. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Albert Namatjira Family Tree diagram — Iltja Ntjarra Many Hands Art Centre". Iltja Ntjarra. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Artists — Iltja Ntjarra Many Hands Art Centre". Iltja Ntjarra. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Albert (Elea) Namatjira's 115th Birthday". www.google.com. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albert Namatjira. |

- Albert Namatjira at the Art Gallery of New South Wales

- Seeing the Centre: The art of Albert Namatjira 1902-1959, a National Gallery of Australia travelling and online exhibition

- Albert Namatjira photograph collection at the National Library of Australia

- Namatjira's works at the National Gallery of Australia

- Australian Dictionary of Biography entry

- ABC schools TV

- Namatjira BIG hART history background and biography.