Aconcagua

| Aconcagua | |

|---|---|

Aconcagua from the south | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 6,960.8 m (22,837 ft) [1] |

| Prominence |

6,960.8 m (22,837 ft) [1] Ranked 2nd |

| Isolation | 16,518 kilometres (10,264 mi) |

| Listing |

Seven Summits Country high point Ultra |

| Coordinates | 32°39′13″S 70°00′40″W / 32.65361°S 70.01111°WCoordinates: 32°39′13″S 70°00′40″W / 32.65361°S 70.01111°W |

| Naming | |

| Pronunciation |

Spanish: [akoŋˈkaɣwa] /ˌækənˈkɑːɡwə/ or /ˌɑːkənˈkɑːɡwə/ |

| Geography | |

Aconcagua Argentina | |

| Location | Mendoza, Argentina |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Climbing | |

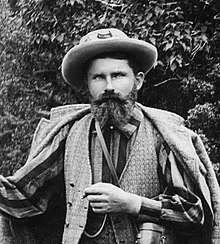

| First ascent |

1897 by Matthias Zurbriggen (first recorded ascent)[2] |

| Easiest route | Scramble (North) |

Aconcagua (Spanish pronunciation: [akoŋˈkaɣwa]), with a summit elevation of 6,960.8 metres (22,837 ft), is the highest mountain in both the Southern and Western Hemispheres.[1] It is located in the Andes mountain range, in the Mendoza Province, Argentina, and lies 112 kilometres (70 mi) northwest of its capital, the city of Mendoza, about five kilometres from San Juan Province and 15 kilometres from the international border with Chile. The mountain itself lies entirely within Argentina, immediately east of Argentina's border with Chile.[3] Its nearest higher neighbor is Tirich Mir in the Hindu Kush, 16,520 kilometres (10,270 mi) away. It is one of the Seven Summits.

Aconcagua is bounded by the Valle de las Vacas to the north and east and the Valle de los Horcones Inferior to the west and south. The mountain and its surroundings are part of the Aconcagua Provincial Park. The mountain has a number of glaciers. The largest glacier is the Ventisquero Horcones Inferior at about 10 kilometres long, which descends from the south face to about 3600 metres in altitude near the Confluencia camp.[4] Two other large glacier systems are the Ventisquero de las Vacas Sur and Glaciar Este/Ventisquero Relinchos system at about 5 kilometres long. The most well-known is the north-eastern or Polish Glacier, as it is a common route of ascent.

Origin of the name

The origin of the name is contested; it is either from the Mapudungun Aconca-Hue, which refers to the Aconcagua River and means "comes from the other side",[3] the Quechua Ackon Cahuak, meaning "'Sentinel of Stone",[5] the Quechua Anco Cahuac, meaning "White Sentinel",[2] or the Aymara Janq'u Q'awa, meaning "White Ravine".[6]

Geologic history

The mountain was created by the subduction of the Nazca Plate beneath the South American Plate. Aconcagua used to be an active stratovolcano (from the Late Cretaceous or Early Paleocene through the Miocene) and consisted of several volcanic complexes on the edge of a basin with a shallow sea. However, sometime in the Miocene, about 8 to 10 million years ago, the subduction angle started to decrease resulting in a stop of the melting and more horizontal stresses between the oceanic plate and the continent, causing the thrust faults that lifted Aconcagua up off its volcanic root. The rocks found on Aconcagua's flanks are all volcanic and consist of lavas, breccias and pyroclastics. The shallow marine basin had already formed earlier (Triassic), even before Aconcagua arose as a volcano. However, volcanism has been present in this region for as long as this basin was around and volcanic deposits interfinger with marine deposits throughout the sequence. The colorful greenish, blueish and grey deposits that can be seen in the Horcones Valley and south of Puente Del Inca, are carbonates, limestones, turbidites and evaporates that filled this basin. The red colored rocks are intrusions, cinder deposits and conglomerates of volcanic origin.[7]

Climbing

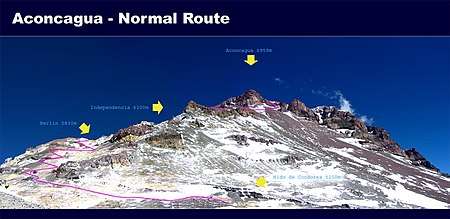

In mountaineering terms, Aconcagua is technically an easy mountain if approached from the north, via the normal route. Aconcagua is arguably the highest non-technical mountain in the world, since the northern route does not absolutely require ropes, axes, and pins. Although the effects of altitude are severe (atmospheric pressure is 40% of sea-level at the summit), the use of supplemental oxygen is not common. Altitude sickness will affect most climbers to some extent, depending on the degree of acclimatization.[8] Even if the normal climb is technically easy, multiple casualties occur every year on this mountain (in January 2009 alone five climbers died). This is due to the large numbers of climbers who make the attempt and because many climbers underestimate the objective risks of the elevation and of cold weather, which is the real challenge on this mountain. Given the weather conditions close to the summit, cold weather injuries are very common.

The Polish Glacier Traverse route, also known as the "Falso de los Polacos" route, crosses through the Vacas valley, ascends to the base of the Polish Glacier, then traverses across to the normal route for the final ascent to the summit. The third most popular route is by the Polish Glacier itself.

Provincial Park rangers do not maintain records of successful summits but estimates suggest a summit rate of 30-40% . About 75% of climbers are foreigners and 25% are Argentinean. Among foreigners, the United States leads in number of climbers, followed by Germany and the UK. About 54% of climbers ascend the Normal Route, 43% up the Polish Glacier Route, and the remaining 3% on other routes.[9]

The routes to the peak from the south and south-west ridges are more demanding and the south face climb is considered quite difficult.

Camps

The camp sites on the normal route are listed below (altitudes are approximate).

- Puente del Inca, 2,740 metres (8,990 ft): A small village on the main road, with facilities including a lodge.

- Confluencia, 3,380 metres (11,090 ft): A camp site a few hours into the national park.

- Plaza de Mulas, 4,370 metres (14,340 ft): Base camp, claimed to be the second largest in the world (after Everest). There are several meal tents, showers and internet access. There is a lodge approx. 1 km from the main campsite across the glacier. At this camp, climbers are screened by a medical team to check if they are fit enough to continue the climb.

- Camp Canadá, 5,050 metres (16,570 ft): A large ledge overlooking Plaza de Mulas.

- Camp Alaska, 5,200 metres (17,060 ft): Called 'change of slope' in Spanish, a small site as the slope from Plaza de Mulas to Nido de Cóndores lessens. Not commonly used.

- Nido de Cóndores, 5,570 metres (18,270 ft): A large plateau with beautiful views. There is usually a park ranger camped here.

- Camp Berlín, 5,940 metres (19,490 ft): The classic high camp, offering reasonable wind protection.

- Camp Colera, 6,000 metres (19,690 ft): A larger, while slightly more exposed, camp situated directly at the north ridge near Camp Berlín, with growing popularity. In January 2011, a shelter was opened in Camp Colera for exclusive use in cases of emergency.[10] The shelter is named Elena after Italian climber Elena Senin, who died in January 2009 shortly after reaching the summit, and whose family donated the shelter.[11]

- Several sites possible for camping or bivouac, including Piedras Blancas (~6100 m) and Independencia (~6350 m), are located above Colera; however, they are seldom used and offer little protection.

Summit attempts are usually made from a high camp at either Berlín or Colera, or from the lower camp at Nido de Cóndores.

History

The first attempt to reach the summit of Aconcagua by a European was made in 1883 by a party led by the German geologist and explorer Paul Güssfeldt. Bribing porters with the story of treasure on the mountain, he approached the mountain via the Rio Volcan, making two attempts on the peak by the north-west ridge and reaching an altitude of 6,500 metres (21,300 ft). The route that he prospected is now the normal route up the mountain.

The first recorded[2] ascent was in 1897 by a European expedition led by the British mountaineer Edward FitzGerald. FitzGerald failed to reach the summit himself over eight attempts between December 1896 and February 1897, but the (Swiss) guide of the expedition, Matthias Zurbriggen reached the summit on January 14. On the final attempt a month later, two other expedition members, Stuart Vines and Nicola Lanti, reached the summit on February 13.[12]

The east side of Aconcagua was first scaled by a Polish expedition, with Konstanty Narkiewicz-Jodko, Stefan Daszyński, Wiktor Ostrowski and Stefan Osiecki summiting on March 9, 1934, over what is now known as the Polish Glacier. A route over the Southwest Ridge was pioneered over seven days in January 1953 by the Swiss-Argentine team of Frederico and Dorly Marmillod, Francisco Ibanez and Fernando Grajales. The famously difficult South Face was conquered by a French team led by René Ferlet. Pierre Lesueur, Adrien Dagory, Robert Paragot, Edmond Denis, Lucien Berardini and Guy Poulet reached the summit after a month of effort on 25 February 1954.[13][14]

The youngest person to reach the summit of Aconcagua was Tyler Armstrong of California. He was nine years old when he reached the summit on December 24, 2013.[15] The oldest person to climb it was Scott Lewis, who reached the summit on November 26, 2007, when he was 87 years old.[16]

In the base camp Plaza de Mulas (at 4300 meters above sea level) there is the highest contemporary art gallery tent called "Nautilus" of the Argentine painter Miguel Doura.[17]

In 2014 Kilian Jornet set a record for climbing and descending Aconcagua from Horcones in 12 hours and 49 minutes.[18] The record was broken less than two months later by Ecuadorian-Swiss Karl Egloff, in a time of 11 hours 52 minutes, nearly an hour faster than Kilian Jornet.[19]

In popular culture

The mountain has a cameo in a 1942 Disney cartoon called Pedro, which features a small, anthropomorphic airplane named Pedro who has a near-disastrous encounter with Aconcagua while carrying mail over the Andes.

Dangers

Aconcagua is the highest peak in the Americas and is also considered an ‘easy’ high altitude peak, being nearly seven thousand metres.[20] And through that, Aconcagua is believed to have the highest death rate of any mountain in South America – around three a year – which has earned it the nickname “Mountain of Death”. More than a hundred people have died on Aconcagua since records began.[21]

Due to the improper disposal of human waste in the mountain environment there are significant health hazards[20] that pose a threat to both animals and human beings.[22] Only boiled or chemically treated water is accepted for drinking. Additionally, Ecofriendly toilets are available only to members of an organised expedition, meaning climbers have to ‘be contracted to a toilet service’ at the base camp and similar camps along the route. Currently, from two base camps (Plaza de Mulas and Plaza Argentina), over 120 barrels of waste (approx. 22,500 kg) are flown out by helicopter each season.[23] In addition, individual mountaineers must make a payment before using these toilets. Some large organisers will give a price up to US$100, some smaller US$5/day or US$10 for the entire stay. Thus, many independent mountaineers defecate on the mountainside.[20]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Informe científico que estudia el Aconcagua: el Coloso de América mide 6.960,8 metros" [Scientific Report on Aconcagua, the Colossus of America measures 6960,8 m] (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. 4 September 2012. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Secor, R.J. (1994). Aconcagua: A Climbing Guide. The Mountaineers. p. 13. ISBN 0-89886-406-2.

There is no definitive proof that the ancient Incas actually climbed to the summit of the White Sentinel [Aconcagua], but there is considerable evidence that they did climb very high on the mountain. Signs of Inca ascents have been found on summits throughout the Andes, thus far the highest atop Llullaillaco, a 6,721-metre (22,051 ft) mountain astride the Chilean-Argentine border in the Atacama region. On Aconcagua, the skeleton of a guanaco was found in 1947 along the ridge connecting the North Summit with the South Summit. It seems doubtful that a guanaco would climb that high on the mountain on its own. Furthermore, an Inca mummy has been found at 5400 m on the south west ridge of Aconcagua, near Cerro Piramidal

- 1 2 Forbes, William (2014). McColl, R.W., ed. Encyclopedia of World Geography, Volume 1 Facts on File Library of World Geography. 1. Infobase Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 0816072299. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ↑ Servei General d'Informacio de Muntanya (2002). Aconcagua 1:50,000 map (Map). Cordee.

- ↑ "South American Explorer". South American Explorers Club (4–19). 1979. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2016 – via University of Texas.

- ↑ "Guías Pedagógicas del Sector Lengua Indígena, Aymara" (PDF) (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Ministerio de Educación, Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia, UNICEF. 2012. p. 62. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013.

- ↑ "Geology of Aconcagua - Volcano - Plate Tectonics". Scribd. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ Muza, SR; Fulco, CS; Cymerman, A (2004). "Altitude Acclimatization Guide". US Army Research Inst. of Environmental Medicine Thermal and Mountain Medicine Division Technical Report (USARIEM–TN–04–05). Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- ↑ Stewart Green. "Aconcagua — Highest Mountain in South America".

- ↑ "TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF USE OF THE "ELENA" SHELTER – ACONCAGUA PROVINCIAL PARK".

- ↑ "Inauguración del refugio Elena".

- ↑ Fitzgerald, E. A. (1898). "On Top of Aconcagua and Tupangato". McClure's magazine. S. S. McClure, Limited. 12 (1): 71–78.

- ↑ R.J. Secor, Aconcagua: A Climbing Guide, The Mountaineers Books, 1999, pp. 17–21

- ↑ Mario Fantin, Some Notes on the History of Aconcagua, The Alpine Journal 1966

- ↑ "Nine-year-old US boy climbs Aconcagua peak in Argentina". BBC News. 28 December 2013.

- ↑ "Récord: un niño de 10 años hizo cumbre en el cerro Aconcagua" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ↑ "Highest contemporary art gallery". Guinness World Records.

- ↑ "Kilian Jornet Smashes Aconcagua Speed Record". Climbing Magazine. 23 December 2014.

- ↑ "Aconcagua Speed Record Smashed Again". Climbing Magazine. 19 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 Apollo, Michal (2016-09-27). "The good, the bad and the ugly – three approaches to management of human waste in a high-mountain environment". International Journal of Environmental Studies. Informa UK Limited. 74 (1): 129–158. doi:10.1080/00207233.2016.1227225. ISSN 0020-7233.

- ↑ "Deaths on Aconcagua - Facts and Figures". www.mountainiq.com. Retrieved 2017-05-25.

- ↑ Cilimburg, A.; Monz, C.; Kehoe, S. (2000). "Wildland recreation and human waste: a review of problems, practices, and concerns". Environmental Management. 25 (6): 587–598. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs002670010046

- ↑ Barros, A. and Pickering, C.M., 2015, Managing human waste on Aconcagua. In: J. Higham, A. Thompson-Carr and G. Musa (Eds.) Mountaineering Tourism (London: Routledge), pp. 219–227.

Bibliography

- Biggar, John (2005). The Andes: A Guide for Climbers (3 ed.). Scotland: Andes Publishing. ISBN 0-9536087-2-7.

- Darack, Ed (2001). Wild Winds: Adventures in the Highest Andes. Cordee / DPP. ISBN 978-1884980817.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Aconcagua. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Aconcagua in Andeshandbook

- "Aconcagua". SummitPost.org. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- Centro de Investigación en Medicina de Altura (CIMA) de Aconcagua, a consortium of researchers and mountaineers working to improve the understanding of high altitude illness.

- Blog with information from a successful Aconcagua ascent

- Live webcam from Aconcagua base camp (December to March)