Access to information

Access to information is the ability for an individual to seek, receive and impart information effectively. This sometimes includes "scientific, indigenous, and traditional knowledge; freedom of information, building of open knowledge resources, including open Internet and open standards, and open access and availability of data; preservation of digital heritage; respect for cultural and linguistic diversity, such as fostering access to local content in accessible languages; quality education for all, including lifelong and e-learning; diffusion of new media and information literacy and skills, and social inclusion online, including addressing inequalities based on skills, education, gender, age, race, ethnicity, and accessibility by those with disabilities; and the development of connectivity and affordable ICTs, including mobile, the Internet, and broadband infrastructures".[1][2]

Michael Buckland defines six types of barriers that have to be overcome in order for access to information to be achieved: identification of the source, availability of the source, price of the user, cost to the provider, cognitive access, acceptability.[3] While “access to information”, “right to information”, “right to know” and “freedom of information” are sometimes used as synonyms, the diverse terminology does highlight particular (albeit related) dimensions of the issue.[1]

Overview

There has been a significant increase in access to the Internet, which reached just over three billion users in 2014, amounting to about 42 per cent of the world’s population.[1] But the digital divide continues to exclude over half of the world’s population, particularly women and girls, and especially in Africa[4] and the least developed countries as well as several Small Island Developing States.[5] Further, individuals with disabilities can either be advantaged or further disadvantaged by the design of technologies or through the presence or absence of training and education.[6]

Context

The Digital Divide

Access to information faces great difficulties because of the global digital divide. A digital divide is an economic and social inequality with regard to access to, use of, or impact of information and communication technologies (ICT).[7] The divide within countries (such as the digital divide in the United States) may refer to inequalities between individuals, households, businesses, or geographic areas, usually at different socioeconomic levels or other demographic categories.[8][7] The divide between differing countries or regions of the world is referred to as the global digital divide, examining this technological gap between developing and developed countries on an international scale.[9]

Gender Divide

Women's freedom of information and access to information is far from being equal to men's. It's the access to information gender divide. Social barriers such as illiteracy and lack of digital empowerment have created stark inequalities in navigating the tools used for access to information, often exacerbating lack of awareness of issues that directly relate to women and gender, such as sexual health. There have also been examples of more extreme measures, such as local community authorities banning or restricting mobile phone use for girls and unmarried women in their communities.[10] A number of States, including some that have introduced new laws since 2010, notably censor voices from and content related to the LGBTQI community, posing serious consequences to access to information about sexual orientation and gender identity.[11] Digital platforms play a powerful role in limiting access to certain content, such as YouTube’s 2017 decision to classify non-explicit videos with LGBTQ themes as ‘restricted’, a classification designed to filter out ‘potentially inappropriate content’.[12]

The security argument

With the evolution of the digital age, application of freedom of speech and its corollaries (freedom of information, access to information) becomes more controversial as new means of communication and restrictions arise including government control or commercial methods putting personal information to danger.[13]

Digital Access

Media and Information Literacy

According to Kuzmin and Parshakova, access to information entails learning in formal and informal education settings. It also entails fostering the competencies of Media and Information Literacy (MIL) that enable users to be empowered and make full use of access to the Internet.[14][15]

The UNESCO's support for journalism education is an example of how UNESCO seeks to contribute to the provision of independent and verifiable information accessible in cyberspace. Promoting access for disabled persons has been strengthened by the UNESCO-convened conference in 2014, which adopted the “New Delhi Declaration on Inclusive ICTs for Persons with Disabilities: Making Empowerment a Reality”.[2]

Open Standards

According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), ""Open Standards" are standards made available to the general public and developed (or approved) and maintained via a collaborative and consensus driven process. "Open Standards" facilitate interoperability and data exchange among different products or services and are intended for widespread adoption." A UNESCO study considers that adopting open standards has the potential to contribute to the vision of a ‘digital commons’ in which citizens can freely find, share, and re-use information.[1] Promoting open source software, which is both free of cost and freely modifiable could help meet the particular needs of marginalized users advocacy on behalf of minority groups, such as targeted outreach, better provision of Internet access, tax incentives for private companies and organizations working to enhance access, and solving underlying issues of social and economic inequalities[1]

Privacy protections

Privacy, surveillance and encryption

The increasing access to and reliance on digital media to receive and produce information have increased the possibilities for States and private sector companies to track individuals’ behaviors, opinions and networks. States have increasingly adopted laws and policies to legalize monitoring of communication, justifying these practices with the need to defend their own citizens and national interests. In parts of Europe, new anti-terrorism laws have enabled a greater degree of government surveillance and an increase in the ability of intelligence authorities to access citizens’ data. While legality is a precondition for legitimate limitations of human rights, the issue is also whether a given law is aligned to other criteria for justification such as necessity, proportionality and legitimate purpose.[2]

International framework

The United Nations Human Rights Council has taken a number of steps to highlight the importance of the universal right to privacy online. In 2015, in a resolution on the right to privacy in the digital age, it established a United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy.[16] In 2017, the Human Rights Council emphasized that the ‘unlawful or arbitrary surveillance and/ or interception of communications, as well as the unlawful or arbitrary collection of personal data, as highly intrusive acts, violate the right to privacy, can interfere with other human rights, including the right to freedom of expression and to hold opinions without interference’.[17]

Regional framework

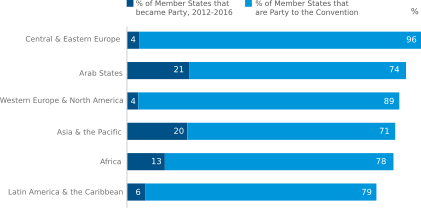

Number of regional efforts, particularly through the courts, to establish regulations that deal with data protection, privacy and surveillance, and which affect their relationship to journalistic uses. The Council of Europe’s Convention 108, the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data, has undergone a modernization process to address new challenges to privacy. Since 2012, four new countries belonging to the Council of Europe have signed or ratified the Convention, as well as three countries that do not belong to the Council, from Africa and Latin America.[18]

Regional courts are also playing a noteworthy role in the development of online privacy regulations. In 2015 the European Court of Justice found that the so-called ‘Safe Harbour Agreement’, which allowed private companies to ‘legally transmit personal data from their European subscribers to the US’,[19] was not valid under European law in that it did not offer sufficient protections for the data of European citizens or protect them from arbitrary surveillance. In 2016, the European Commission and United States Government reached an agreement to replace Safe Harbour, the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield, which includes data protection obligations on companies receiving personal data from the European Union, safeguards on United States government access to data, protection and redress for individuals, and an annual joint review to monitor implementation.[20]

The European Court of Justice’s 2014 decision in the Google Spain case allowed people to claim a ‘right to be forgotten’ or ‘right to be de-listed’ in a much-debated approach to the balance between privacy, free expression and transparency.[21] Following the Google Spain decision the ‘right to be forgotten’ or ‘right to be de-listed’ has been recognized in a number of countries across the world, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean.[22][23]

Recital 153 of the European Union General Data Protection Regulation[24] states "Member States law should reconcile the rules governing freedom of expression and information, including journalistic…with the right to the protection of personal data pursuant to this Regulation. The processing of personal data solely for journalistic purposes…should be subject to derogations or exemptions from certain provisions of this Regulation if necessary to reconcile the right to the protection of personal data with the right to freedom of expression and information, as enshrined in Article 11 of the Charter."[25]

National framework

The number of countries around the world with data protection laws has also continued to grow. According to the World Trends Report 2017/2018, between 2012 and 2016, 20 UNESCO Member States adopted data protection laws for first time, bringing the global total to 101.[26] Of these new adoptions, nine were in Africa, four in Asia and the Pacific, three in Latin America and the Caribbean, two in the Arab region and one in Western Europe and North America. During the same period, 23 countries revised their data protection laws, reflecting the new challenges to data protection in the digital era.[2]

According to Global Partners Digital, only four States have secured in national legislation a general right to encryption, and 31 have enacted national legislation that grants law enforcement agencies the power to intercept or decrypt encrypted communications.[27]

Private sector implications

Since 2010, to increase the protection of the information and communications of their users and to promote trust in their services’.[28] High profile examples of this have been WhatsApp’s implementation of full end-to-end encryption in its messenger service,[29] and Apple’s contestation of a law enforcement request to unlock an iPhone used by the perpetrators of a terror attack.[30]

Protection of confidential sources and whistle-blowing

Rapid changes in the digital environment, coupled with contemporary journalist practice that increasingly relies on digital communication technologies, pose new risks for the protection of journalism sources. Leading contemporary threats include mass surveillance technologies, mandatory data retention policies, and disclosure of personal digital activities by third party intermediaries. Without a thorough understanding of how to shield their digital communications and traces, journalists and sources can unwittingly reveal identifying information.[31] Employment of national security legislation, such as counter-terrorism laws, to override existing legal protections for source protection is also becoming a common practice.[31] In many regions, persistent secrecy laws or new cybersecurity laws threaten the protection of sources, such as when they give governments the right to intercept online communications in the interest of overly broad definitions of national security.[32]

Developments in regards to source protection laws have occurred between 2007 and mid-2015 in 84 (69 per cent) of the 121 countries surveyed.[33] The Arab region had the most notable developments, where 86 per cent of States had demonstrated shifts, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (85 per cent), Asia and the Pacific (75 per cent), Western Europe and North America (66 per cent) and finally Africa, where 56 per cent of States examined had revised their source protection laws.[33]

As of 2015, at least 60 States had adopted some form of whistle-blower protection.[34] At the international level, the United Nations Convention against Corruption entered into force in 2005.[35] By July 2017, the majority of countries around the globe, 179 in total, had ratified the Convention, which includes provisions for the protection of whistleblowers.[36]

Regional conventions against corruption that contain protection for whistle-blowers have also been widely ratified. These include the Inter-American Convention against Corruption, which has been ratified by 33 Member States,[37] and the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption, which was ratified by 36 UNESCO Member States.[38]

In 2009, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Council adopted the Recommendation for Further Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions.[39]

Media Pluralism

According to the World Trends Report, access to a variety of media increased between 2012 and 2016. The internet has registered the highest growth in users supported by massive investments in infrastructure and significant uptake in mobile usage.[2]

Internet mobile

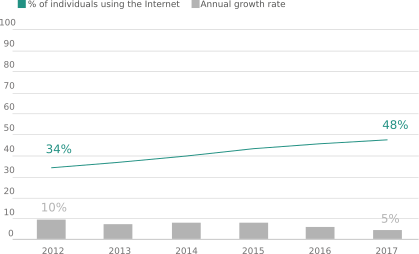

The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the work of the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development, co-chaired by UNESCO, and the Internet Governance Forum’s intersessional work on ‘Connecting the Next Billion' are proof of the international commitments towards providing Internet access for all. According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), by the end of 2017, an estimated 48 per cent of individuals regularly connect to the internet, up from 34 per cent in 2012.[40] Despite the significant increase in absolute numbers, however, in the same period the annual growth rate of internet users has slowed down, with five per cent annual growth in 2017, dropping from a 10 per cent growth rate in 2012.[41]

The number of unique mobile cellular subscriptions increased from 3.89 billion in 2012 to 4.83 billion in 2016, two-thirds of the world’s population, with more than half of subscriptions located in Asia and the Pacific. The number of subscriptions is predicted to rise to 5.69 billion users in 2020. As of 2016, almost 60 per cent of the world’s population had access to a 4G broadband cellular network, up from almost 50 per cent in 2015 and 11 per cent in 2012.[42]

The limits that users face on accessing information via mobile applications coincide with a broader process of fragmentation of the internet. Zero-rating, the practice of internet providers allowing users free connectivity to access specific content or applications for free, has offered some opportunities for individuals to surmount economic hurdles, but has also been accused by its critics as creating a ‘two-tiered’ internet. To address the issues with zero-rating, an alternative model has emerged in the concept of ‘equal rating’ and is being tested in experiments by Mozilla and Orange in Africa. Equal rating prevents prioritization of one type of content and zero-rates all content up to a specified data cap. Some countries in the region had a handful of plans to choose from (across all mobile network operators) while others, such as Colombia, offered as many as 30 pre-paid and 34 post-paid plans.[43]

Broadcast media

In Western Europe and North America, the primacy of television as a main source of information is being challenged by the internet, while in other regions, such as Africa, television is gaining greater audience share than radio, which has historically been the most widely accessed media platform.[2] Age plays a profound role in determining the balance between radio, television and the internet as the leading source of news. According to the 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, in 36 countries and territories surveyed, 51 per cent of adults 55 years and older consider television as their main news source, compared to only 24 per cent of respondents between 18 and 24.[44] The pattern is reversed when it comes to online media, chosen by 64 per cent of users between 18 and 24 as their primary source, but only by 28 per cent of users 55 and older.[44] According to the Arab Youth Survey, in 2016, 45 per cent of the young people interviewed considered social media as a major source of news.[45]

Satellite television has continued to add global or transnational alternatives to national viewing options for many audiences. Global news providers such as the BBC, Al Jazeera, Agence France-Presse, RT (formerly Russia Today) and the Spanish-language Agencia EFE, have used the internet and satellite television to better reach audiences across borders and have added specialist broadcasts to target specific foreign audiences. Reflecting a more outward looking orientation, China Global Television Network (CGTN), the multi-language and multi-channel grouping owned and operated by China Central Television, changed its name from CCTV-NEWS in January 2017. After years of budget cuts and shrinking global operations, in 2016 BBC announced the launch of 12 new language services (in Afaan Oromo, Amharic, Gujarati, Igbo, Korean, Marathi, Pidgin, Punjabi, Telugu, Tigrinya, and Yoruba), branded as a component of its biggest expansion ‘since the 1940s’.[46]

Also expanding access to content are changes in usage patterns with non-linear viewing, as online streaming is becoming an important component of users’ experience. Since expanding its global service to 130 new countries in January 2016, Netflix experienced a surge in subscribers, surpassing 100 million subscribers in the second quarter of 2017, up from 40 million in 2012. The audience has also become more diverse with 47 per cent of users based outside of the United States, where the company began in 1997.[47]

Newspaper industry

The Internet has challenged the press as an alternative source of information and opinion but has also provided a new platform for newspaper organizations to reach new audiences. Between 2012 and 2016, print newspaper circulation continued to fall in almost all regions, with the exception of Asia and the Pacific, where the dramatic increase in sales in a few select countries has offset falls in historically strong Asian markets such as Japan and the Republic of Korea. Between 2012 and 2016, India’s print circulation grew by 89 per cent.[48] As many newspapers make the transition to online platforms, revenues from digital subscriptions and digital advertising have been growing significantly. How to capture more of this growth remains a pressing challenge for newspapers.[48]

International framework

UNESCO's work

Mandate

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015, includes Goal 16.10 to ‘ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements’[49]. UNESCO has been assigned as the custodian agency responsible for global reporting on indicator 16.10.2 regarding the ‘number of countries that adopt and implement constitutional, statutory and/or policy guarantees for public access to information’.[50] This responsibility aligns with UNESCO’s commitment to promote universal access to information, grounded in its constitutional mandate to ‘promote the free flow of ideas by word and image’. In 2015, UNESCO’s General Conference proclaimed 28 September as the International Day for Universal Access to Information.[51] The following year, participants of UNESCO’s annual celebration of World Press Freedom Day adopted the Finlandia Declaration on access to information and fundamental freedoms, 250 years after the first freedom of information law was adopted in what is modern day Finland and Sweden.[52]

History

- 38th Session of the General Conference in 2015, Resolution 38 C/70 proclaiming 28 September as the "International Day for the Universal Access to Information

- Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights[53]

- Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[54]

- Brisbane Declaration[55]

- Dakar Declaration[56]

- Finlandia Declaration[57]

- Maputo Declaration[58]

- New Delhi Declaration[59]

- Recommendation concerning the Promotion and Use of Multilingualism and Universal Access to Cyberspace 2003[60]

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities[61]

The International Programme for Development of Communication

The International Programme for the Development of Communication (IPDC) is a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) programme aimed at strengthening the development of mass media in developing countries. Its mandate since 2003 is “... to contribute to sustainable development, democracy and good governance by fostering universal access to and distribution of information and knowledge by strengthening the capacities of the developing countries and countries in transition in the field of electronic media and the printed press.[62]

The International Programme for the Development of Communication is responsible for the follow-up of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16 through indicators 16.10.1 and 16.10.2. Every two years, a report containing information from the Member States on the status of judicial inquiries on each of the killings condemned by UNESCO is submitted to the IPDC Council by UNESCO's Director-General.[63] The journalists safety indicators are a tool developed by UNESCO which, according to UNESCO's website, aims on mapping the key features that can help assess safety of journalists, and help determine whether adequate follow-up is given to crimes committed against them. The IPDC Talks also allow the Programme to raise awareness on the importance of access to information.[64] The IPDC is also the programme that monitors and reports on access to information laws around the world through the United Nations Secretary-General global report on follow-up to SDGs.[2]

On 28 September 2015, UNESCO adopted the International Day for the Universal Access to Information during its 38th session.[65] During the International Day, the IPDC organized the “IPDC Talks: Powering Sustainable Development with Access to Information” event, which gathered high-level participants.[66] The annual event aims on highlighting the “importance of access to information” for sustainable development.

The Internet Universality framework

Internet Universality is the concept that "the Internet is much more than infrastructure and applications, it is a network of economic and social interactions and relationships, which has the potential to enable human rights, empower individuals and communities, and facilitate sustainable development. The concept is based on four principles stressing the Internet should be Human rights-based, Open, Accessible, and based on Multistakeholder participation. These have been abbreviated as the R-O-A-M principles. Understanding the Internet in this way helps to draw together different facets of Internet development, concerned with technology and public policy, rights and development."[67]

Through the concept internet universality UNESCO highlights access to information as a key to assess a better Internet environment. There is special relevance to the Internet of the broader principle of social inclusion. This puts forward the role of accessibility in overcoming digital divides, digital inequalities, and exclusions based on skills, literacy, language, gender or disability. It also points to the need for sustainable business models for Internet activity, and to trust in the preservation, quality, integrity, security, and authenticity of information and knowledge. Accessibility is interlinked to rights and openness.[1] Based on the ROAM principles, UNESCO is now developing Internet Universality indicators to help governments and other stakeholders assess their own national Internet environments and to promote the values associated with Internet Universality, such as access to information.[68]

The World Bank initiatives

In 2010, the World Bank launched the World Bank policy on access to information, which constitutes a major shift in the World Bank's strategy.[69] The principle binds the World Bank to disclose any requested information, unless it is on a "list of exception":

- "Personal information

- Communications of Governors and/or Executive Directors’ Offices

- Ethics Committee

- Attorney-Client Privilege

- Security and Safety Information

- Separate Disclosure Regimes

- Confidential Client/Third Party Information

- Corporate Administrative

- Deliberative Information*

- Financial Information"[70]

The World Bank is prone to Open Developments with its Open data, Open Finance and Open knowledge repository.[70]

The World Summit on the Information Societies

The World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) was a two-phase United Nations-sponsored summit on information, communication and, in broad terms, the information society that took place in 2003 in Geneva and in 2005 in Tunis. One of its chief aims was to bridge the global digital divide separating rich countries from poor countries by spreading access to the Internet in the developing world. The conferences established 17 May as World Information Society Day.[71]

Regional framework

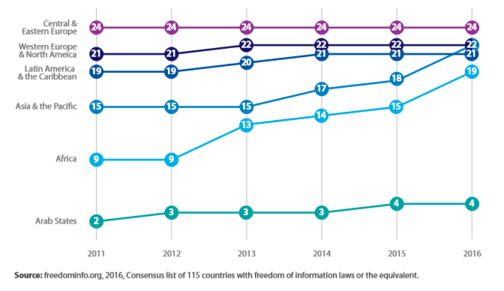

The results from UNESCO monitoring of SDG 16.10.2 show that 112 countries have now adopted freedom of information legislation or similar administrative regulations.[72][2] Of these, 22 adopted new legislation since 2012. At the regional level, Africa has seen the highest growth, with 10 countries adopting freedom of information legislation in the last five years, more than doubling the number of countries in the region to have such legislation from nine to 19. A similarly high growth rate has occurred in the Asia-Pacific region, where seven countries adopted freedom of information laws in the last five years, bringing the total to 22. In addition, during the reporting period, two countries in the Arab region, two countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, and one country in Western Europe and North America adopted freedom of information legislation. The vast majority of the world’s population now lives in a country with a freedom of information law, and several countries currently have freedom of information bills under consideration.[2]

National framework

Freedom of information laws

While there has been an increase in countries with freedom of information laws, their implementation and effectiveness vary considerably across the world. The Global Right to Information Rating is a programme providing advocates, legislators, reformers with tools to assess the strength of a legal framework.[73] In measuring the strength and legal framework of each country’s freedom of information law using the Right to Information Rating, one notable trend appears.[74] Largely regardless of geographic location, top scoring countries tend to have younger laws.[75] According to the United Nations Secretary General’s 2017 report on the Sustainable Development Goals, to which UNESCO contributed freedom of information-related information, of the 109 countries with available data on implementation of freedom of information laws, 43 per cent do not sufficiently provide for public outreach and 43 per cent have overly-wide definitions of exceptions to disclosure, which run counter to the aim of increased transparency and accountability.[76]

Despite the adoption of freedom of information laws; officials are often unfamiliar with the norms of transparency at the core of freedom of information or are unwilling to recognize them in practice. Journalists often do not make effective use of freedom of information laws for a multitude of reasons: official failure to respond to information requests, extensive delays, receipt of heavily redacted documents, arbitrarily steep fees for certain types of requests, and a lack of professional training.[77]

Debates around public access to information have also focused on further developments in encouraging open data approaches to government transparency. In 2009, the data.gov portal was launched in the United States, collecting in one place most of the government open data; in the years following, there was a wave of government data opening around the world. As part of the Open Government Partnership, a multilateral network established in 2011, some 70 countries have now issued National Action Plans, the majority of which contain strong open data commitments designed to foster greater transparency, generate economic growth, empower citizens, fight corruption and more generally enhance governance. In 2015 the Open Data Charter was founded in a multistakeholder process in order to establish principles for ‘how governments should be publishing information’.[78] The Charter has been adopted by 17 national governments half of which were from Latin America and the Caribbean.[79]

The 2017 Open Data Barometer, conducted by the World Wide Web Foundation, shows that while 79 out of the 115 countries surveyed have open government data portals, in most cases ‘the right policies are not in place, nor is the breadth and quality of the data-sets released sufficient’. In general, the Open Data Barometer found that government data is usually ‘incomplete, out of date, of low quality, and fragmented’.[80][2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Keystones to foster inclusive Knowledge Societies (PDF). UNESCO. 2015. p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development Global Report 2017/2018. http://www.unesco.org/ulis/cgi-bin/ulis.pl?catno=261065&set=005B054385_2_76&gp=1&lin=1&ll=1: UNESCO. 2018. p. 202.

- ↑ "Access to information". people.ischool.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ↑ "Recommendation s concerning the promotion and use of multilinguisme and universal access to cyberspace" (PDF).

- ↑ Souter, David (2010). "Towards Inclusive Knowledge Societies: A Review of UNESCO Action in Implementing the WSIS Outcomes" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org.

- ↑ "Photos" (PDF).

- 1 2 "FALLING THROUGH THE NET: A Survey of the "Have Nots" in Rural and Urban America | National Telecommunications and Information Administration". www.ntia.doc.gov. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ↑ Norris, Pippa; Norris, McGuire Lecturer in Comparative Politics Pippa (2001-09-24). Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00223-3.

- ↑ Lee, Jaewoo; Andreoni, James; Bagwell, Kyle; Cripps, Martin W.; Chinn, Menzie David; Durlauf, Steven N.; Brock, William A.; Che, Yeon-Koo; Cohen-Cole, Ethan (2004). The Determinants of the Global Digital Divide: A Cross-country Analysis of Computer and Internet Penetration. Social Systems Research Institute, University of Wisconsin.

- ↑ "'Chupke, Chupke': Going Behind the Mobile Phone Bans in North India". genderingsurveillance.internetdemocracy.in. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ↑ "Deeplinks Blog". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ↑ Hunt, Elle. 2017. LGBT community anger over YouTube restrictions which make their videos invisible. The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/mar/20/lgbt-communityanger-over-youtube-restrictions-whichmake-their-videos-invisible

- ↑ Wolfgang, Schultz; van Hoboken, Joris (2016). Human rights and encryption. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002465/246527e.pdf: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100185-7.

- ↑ Kuzmin, E., and Parshakova, A. (2013), Media and Information Literacy for Knowledge Societies. Translated by Butkova, T., Kuptsov, Y., and Parshakova, A. Moscow: Interregional Library Cooperation Centre for UNESCO. http://www.ifapcom.ru/files/News/Images/2013/mil_eng_web.pdf#page=24

- ↑ UNESCO (2013a), UNESCO Communication and Information Sector with UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Global Media and Information Literacy Assessment Framework: Country Readiness and Competencies. Paris: UNESCO. Available online at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002246/224655e.pdf

- ↑ UN Human Rights Council. 2016. The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet. A/HRC/32/13. Available at http://www.un.org/en/ga/71/meetings/. Accessed 23 June 2017.

- ↑ UN Human Rights Council. 2017. The right to privacy in the digital age. A/HRC/34/L.7/ Rev.1. Available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/HRC/34/L.7/Rev.1. Accessed 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Council of Europe. 2017. Chart of signatures and ratifications of Treaty 108. Council of Europe Treaty Office. Available at http://www.coe.int/web/conventions/full-list. Accessed 7 June 2017.

- ↑ European Commission. n.d. The EU-U.S. Privacy Shield. Justice. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/data-transfers-outside-eu/eu-us-privacy-shield_en

- ↑ European Commission. n.d. The EU-U.S. Privacy Shield. Justice. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/data-transfers-outside-eu/eu-us-privacy-shield_en.

- ↑ Cannataci, Joseph A., Bo Zhao, Gemma Torres Vives, Shara Monteleone, Jeanne Mifsud Bonnici, and Evgeni Moyakine. 2016. Privacy, free expression and transparency: Redefining their new boundaries in the digital age. Paris: UNESCO.

- ↑ Keller, Daphne. 2017. Europe’s “Right to Be Forgotten” in Latin America. In Towards an Internet Free of Censorship II: Perspectives in Latin America. Centro de Estudios en Libertad de Expresión y Acceso a la Información (CELE), Universidad de Palermo.

- ↑ Santos, Gonzalo. 2016. Towards the recognition of the right to be forgotten in Latin America. ECIJA. Available at http://ecija.com/en/salade-prensa/towards-the-recognition-of-theright-to-be-forgotten-in-latin-america/.

- ↑ EU GDPR 2016. EU General Data Protection Regulation 2016/67: Recital 153. Text. Available at http://www.privacyregulation.eu/en/r153.htm. Accessed 7 June 2017.

- ↑ Schulz, Wolfgang, and Joris van Hoboken. 2016a. Human rights and encryption. UNESCO Series on Internet Freedom. Paris, France: UNESCO Pub.; Sense. Available at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002465/246527e.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Greenleaf, Graham. 2017. Global Tables of Data Privacy Laws and Bills (5th ed.). Privacy Laws & Business International Report.

- ↑ Global Partners Digital. n.d. World map of encryption laws and policies. Available at https://www.gp-digital.org/nationalencryption-laws-and-policies/.

- ↑ Schulz, Wolfgang, and Joris van Hoboken. 2016b. Human rights and encryption. UNESCO series on internet freedom. France. Available at http://www.unesco.org/ulis/cgi-bin/ulis.pl?catno=246527.

- ↑ WhatsApp. 2016. end-to-end encryption. WhatsApp.com. Available at https://blog.whatsapp.com/10000618/end-to-endencryption. Accessed 25 May 2017.

- ↑ Lichtblau, Eric, and Katie Benner. 2016. Apple Fights Order to Unlock San Bernardino Gunman’s iPhone. The New York Times. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/18/technology/appletimothy-cook-fbi-san-bernardino.html. Accessed 25 May 2017.

- 1 2 Open Society Justice Initiative. 2013. The Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information (Tshwane Principles). New York: Open Society Foundations.

- ↑ Posetti, Julie. 2017a. Protecting Journalism Sources in the Digital Age. UNESCO Series on Internet Freedom. Paris, France: UNESCO Publishing. Available at http://www.unesco.org/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CI/CI/pdf/protecting_journalism_sources_in_digital_age.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2017.

- 1 2 Posetti, Julie. 2017b. Fighting back against prolific online harassment: Maria Ressa. Article in Kilman, L. 2017. An Attack on One is an Attack on All: Successful Initiatives To Protect Journalists and Combat Impunity. International Programme for the Development of Communication, Paris, France: UNESCO Publishing. Available at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0025/002593/259399e.pdf.

- ↑ Kaye, David. 2015a. Promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression. United Nations General Assembly. Available at http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/70/361.

- ↑ UN Office on Drugs and Crime. 2005. UN Convention against Corruption, A/58/422. Available at https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/Publications/ Convention/08-50026_E.pdf . Accessed 25 May 2017.

- ↑ UN Office on Drugs and Crime. 2017. Convention against Corruption: Signature and Ratification Status. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Available at https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/corruption/ratification-status.html/. Accessed 25 June 2017.

- ↑ Organization of American States. n.d. InterAmerican Convention Against Corruption: Signatories and Ratifications. Available at http://www.oas.org/en/sla/dil/inter_american_treaties_B-58_against_ Corruption_signatories.asp>.

- ↑ African Union. 2017. List of countries which have signed, ratified/acceded to the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption. Available at https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/7786-sl-african_union_ convention_on_preventing_and_ combating_corruption_9.pdf.

- ↑ OECD. 2016. Committing to Effective Whistleblower Protection. Paris. Available at http://www.oecd.org/corporate/committing-to-effective-whistleblowerprotection-9789264252639-en.htm . Accessed 25 June 2017.

- ↑ International Telecommunication Union (ITU). 2017a. Key ICT indicators for developed and developing countries and the world (totals and penetration rates). World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators database. Available at https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx.

- ↑ International Telecommunication Union (ITU). 2017b. Status of the transition to Digital Terrestrial Television Broadcasting: Figures. ITU Telecommunication Development Sector. Available at http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Spectrum-Broadcasting/Pages/DSO/figures.aspx .

- ↑ GSMA. 2017. The Mobile Economy 2017. Available at https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/.

- ↑ Galpaya, Helani. 2017. Zero-rating in Emerging Economies. London: Chatham House. Available at https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/GCIG%20 no.47_1.pdf.

- 1 2 Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2017. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available at https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital%20News%20Report%202017%20 web_0.pdf.

- ↑ ASDA’A Burson-Marsteller. 2016. Arab Youth Survey Middle East – Findings. Available at http://www.arabyouthsurvey.com/. Accessed 19 June 2017.

- ↑ BBC. 2016. BBC World Service announces biggest expansion ‘since the 1940s’. BBC News, sec. Entertainment & Arts. Available at https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainmentarts-37990220. Accessed 21 August 2017.

- ↑ Huddleston, Tom. 2017. Netflix Has More U.S. Subscribers Than Cable TV. Fortune. Available at http://fortune.com/2017/06/15/netflix-more-subscribersthan-cable/. Accessed 21 August 2017.

- 1 2 Campbell, Cecilia. 2017. World Press Trends 2017. Frankfurt: WAN-IFRA.

- ↑ UN General Assembly. 2015b. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1. Available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E>. Accessed 24 May 2017.

- ↑ UNESCO. 2016c. Unpacking Indicator 16.10.2: Enhancing public access to information through Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. Available at <http://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/unpacking_indicator16102.pdf.

- ↑ UNESCO. 2015. 38 C/70. Proclamation of 28 September as the ‘International Day for the Universal Access to Information’. Available at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002352/235297e.pdf.

- ↑ UNESCO. 2016a. Finlandia Declaration: Access to Information and Fundamental Freedoms – This is Your Right! Available at https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/finlandia_ declaration_3_may_2016.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2017.

- ↑ "Resolution" (PDF). www.ohchr.org.

- ↑ "Treaty" (PDF). treaties.un.org.

- ↑ "Brisbane Declaration – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org.

- ↑ "Dakar Declaration – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org.

- ↑ "Declaration" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org.

- ↑ "Maputo declaration – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org.

- ↑ "Images" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org.

- ↑ "Recommendation concerning the promotion and use of multilingualism and universal access to cyberspace" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ↑ "Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – Articles – United Nations Enable". www.un.org.

- ↑ Amendments to the Statutes of the International Programme for The Development of Communication (IPDC) Resolution 43/32, adopted on the Report of Commission V at the 18th Plenary Meeting, on 15 October 2003.

- ↑ http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002460/246014E.pdf https://en.unesco.org/programme/ipdc/initiatives

- ↑ "About the IPDCtalks". UNESCO.

- ↑ "Images" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org.

- ↑ "International Day for Universal Access to Information". UNESCO.

- ↑ "Internet Universality". UNESCO. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ↑ "Freedom of Expression on the Internet". UNESCO. 25 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ "Overview".

- 1 2 "Brochure" (PDF). pubdocs.worldbank.org.

- ↑ "About – WSIS Forum 2018". www.itu.int.

- ↑ freedominfo.org 2016.

- ↑ "Global Right to Information Rating". Global Right to Information Rating.

- ↑ Centre for Law and Democracy & Access Info. 2017b. Global Right to Information Rating Map. Global Right to Information Rating. Available at http://www.rti-rating.org/. Accessed 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Centre for Law and Democracy & Access Info. 2017a. About. Global Right to Information Rating. Available at http://www.rti-rating.org/about/. Accessed 24 May 2017.

- ↑ United Nations. 2017. Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017. Available at https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2017/.

- ↑ Trapnell, Stephanie (editor). 2014. Right to Information: Case Studies on Implementation. Washington D. C.: World Bank Group. Available at http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/462751468000583408/pdf/98720-WPP118353-Box393176B-PUBLIC-RTI-CaseStudies-Implementation-WEBfinal.pdf.

- ↑ Open Data Charter. 2017b. Who we are. Open Data Charter. Available at https://opendatacharter.net/who-we-are/. Accessed 24 May 2017

- ↑ Open Data Charter. 2017a. Adopted By. Open Data Charter. Available at https://opendatacharter.net/adopted-by-countries-and-cities/. Accessed 24 May 2017.

- ↑ World Wide Web Foundation. 2017. Open Data Barometer: Global Report Fourth Edition. Available at http://opendatabarometer.org/doc/4thEdition/ODB-4thEditionGlobalReport.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2017.

Sources