Abyssal zone

| Aquatic layers |

|---|

| Stratification |

| See also |

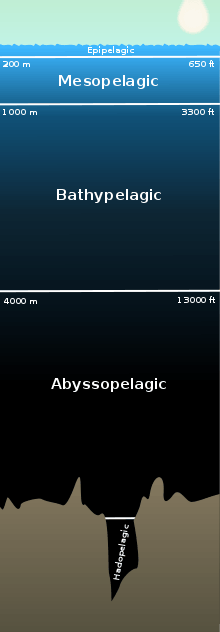

The abyssal zone or abyssopelagic zone is a layer of the pelagic zone of the ocean. "Abyss" derives from the Greek word ἄβυσσος, meaning bottomless. At depths of 4,000 to 6,000 metres (13,000 to 20,000 ft), this zone remains in perpetual darkness. These regions are also characterized by continuous cold and lack of nutrients.The abyssal zone has temperatures around 2 to 3 °C (36 to 37 °F) through the large majority of its mass.[1] It is the deeper part of the midnight zone which starts in the bathypelagic waters above.[1][2]

The area below the abyssal zone is the sparsely inhabited hadal zone.[3] The zone above is the bathyal zone.[3]

Trenches

The deep trenches or fissures that plunge down thousands of metres below the ocean floor (for example, the midoceanic trenches such as the Mariana Trench in the Pacific) are almost unexplored.[2] Previously, only the bathyscaphe Trieste, the remote control submarine Kaikō and the Nereus have been able to descend to these depths.[4][5] However, as of March 25, 2012 one vehicle, the Deepsea Challenger was able to penetrate to a depth of 10,898.4 metres (35,756 ft).

Biology

Overall, the deep sea is a very food-limited environment. In the abyssal zone, biomass is directly related to the amount of food either supplied from transporting ocean currents or from the water column above. The biological pump is thought of as the main driver for cycling organic matter (e.g. particulate organic carbon or dissolved organic carbon) from the atmosphere into the surface ocean, and eventually to the deep ocean.[6]

Due to the fact that organisms in the abyssal zone have no access to sunlight, they rely heavily on nutrients sinking from above (known as marine snow). These nutrients can be in the form of sediments, algae, fecal pellets, or fish carcasses, to name a few. Spatially, the abundance of organisms in the deep ocean is hypothesized to be highest where the surface productivity is the highest, as long as there is efficient export from surface ocean to deep ocean. Studies have shown that marine snow alone does not supply an adequate amount of nutrients to support the population of benthic organisms. However, population booms of algae or animals near the surface ocean can result in heavy pulses of particulate organic matter that, in a few weeks, will deliver as many nutrients as would normally be delivered over decadal timescales of marine snow transport.[7]

Some sea floor locations, such as mid-ocean ridges, are unique in that they contain hydrothermal vents. These vents emit geothermically reduced sulfur compounds that allow for microbial primary production, sustaining many benthic organisms in absence of the sunlight required for photosynthesis.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Deep Sea Biome". Untamed Science. Archived from the original on 31 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- 1 2 Nelson, Rob (April 2007). "Abyssal". The Wild Classroom. Archived from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- 1 2 "Abyssal". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ↑ "History of the Bathyscaph Trieste". Bathyscaphtrieste.com. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ↑ "World's deepest-diving submarine missing". USA Today. Gannett Company Inc. 2003-07-02. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ↑ Glover (2010). "Temporal Change in Deep-Sea Benthic Ecosystems: A Review of the Evidence From Recent Time-Series Studies". Advances in Marine Biology. 58: 10–12. doi:10.1016/S0065-2881(10)58001-5.

- ↑ "Marine biology: Feast and famine on the abyssal plain". ScienceDaily. Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. November 11, 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ Karl, D.M.; Wirsen, C.O.; Jannasch, H.W. (March 21, 1980). "Deep-sea primary production at the Galapagos hydrothermal vents". Science. 207.