Shakuntala (play)

Shakuntala, also known as The Recognition of Shakuntala, The Sign of Shakuntala, and many other variants (Devanagari: अभिज्ञानशाकुन्तलम् – Abhijñānashākuntala), is a Sanskrit play by the ancient Indian poet Kālidāsa, dramatizing the story of Shakuntala told in the epic Mahabharata. It is considered to be the best of Kālidāsa's works.[1] Its date is uncertain, but Kālidāsa is often placed in the period between the 1st century BCE and 4th century CE.[2]

Origin of Kālidāsa's play

Shakuntala elaborates upon an episode mentioned in the Mahabharata, with minor changes made (by Kālidāsa) to the plot.

Title

Manuscripts differ on what its exact title is. Usual variants are Abhijñānaśakuntalā, Abhijñānaśākuntala, Abhijñānaśakuntalam and the "grammatically indefensible" Abhijñānaśākuntalam.[3] The Sanskrit title means pertaining to the recognition of Shakuntala, so a literal translation could be Of Shakuntala who is recognized. The title is sometimes translated as The token-for-recognition of Shakuntala or The Sign of Shakuntala. Titles of the play in published translations include Sacontalá or The Fatal Ring and Śakoontalá or The Lost Ring.[4][5]

Synopsis

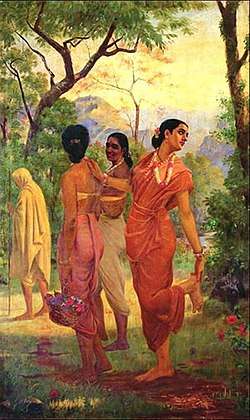

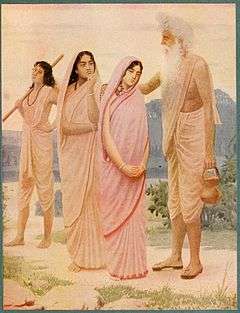

The protagonist is Shakuntala, daughter of the sage Vishwamitra and the apsara Menaka. Abandoned at birth by her parents, Shakuntala is reared in the secluded hermitage of the sage Kanva, and grows up a comely but innocent maiden.

While Kanva and the other elders of the hermitage are away on a pilgrimage, Dushyanta, king of Hastinapura, comes hunting in the forest and chances upon the hermitage. He is captivated by Shakuntala, courts her in royal style, and marries her. He then has to leave to take care of affairs in the capital. She is given a ring by the king, to be presented to him when she appears in his court. She can then claim her place as queen.

The anger-prone sage Durvasa arrives when Shakuntala is lost in her fantasies, so that when she fails to attend to him, he curses her by bewitching Dushyanta into forgetting her existence. The only cure is for Shakuntala to show him the signet ring that he gave her.

She later travels to meet him, and has to cross a river. The ring is lost when it slips off her hand when she dips her hand in the water playfully. On arrival the king refuses to acknowledge her. Shakuntala is abandoned by her companions, who return to the hermitage.

Fortunately, the ring is discovered by a fisherman in the belly of a fish, and Dushyanta realises his mistake - too late. The newly wise Dushyanta defeats an army of Asuras, and is rewarded by Indra with a journey through heaven. Returned to Earth years later, Dushyanta finds Shakuntala and their son by chance, and recognizes them.

In other versions, especially the one found in the Mahabharata, Shakuntala is not reunited until her son Bharata is born, and found by the king playing with lion cubs. Dushyanta enquires about his parents to young Bharata and finds out that Bharata is indeed his son. Bharata is an ancestor of the lineages of the Kauravas and Pandavas, who fought the epic war of the Mahabharata. It is after this Bharata that India was given the name "Bharatavarsha", the 'Land of Bharata'.[6]

Reception

By the 18th century, Western poets were beginning to get acquainted with works of Indian literature and philosophy. Shakuntala was the first Indian drama to be translated into a Western language, by Sir William Jones in 1789. In the next 100 years, there were at least 46 translations in twelve European languages.[7]

Sanskrit literature

Introduction in the West

Sacontalá or The Fatal Ring, Sir William Jones' translation of Kālidāsa's play, was first published in Calcutta, followed by European republications in 1790, 1792 and 1796.[4][8] A German and a French version of Jones' translation were published in 1791 and 1803 respectively.[8][9][10] Goethe published an epigram about Shakuntala in 1791, and in his Faust he adopted a theatrical convention from the prologue of Kālidāsa's play.[8] Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel's plan to translate Shakuntala in German never materialised, but he did however publish a translation of the Mahabharata version of Shakuntala's story in 1808.[11]Goethe's epigram goes like this[12]:

Wilt thou the blossoms of spring and the fruits that are later in season,

Wilt thou have charms and delights,

Wilt thou have strength and support,

Wilt thou with one short word encompass the earth and the heaven,

All is said if I name only, Shakuntla, thee.

Unfinished opera projects

When Leopold Schefer became a student of Antonio Salieri in September 1816, he had been working on an opera about Shakuntala for at least a decade, a project which he did however never complete.[13] Franz Schubert, who had been a student of Salieri until at least December of the same year, started composing his Sakuntala opera, D 701, in October 1820.[13][14] Johann Philipp Neumann based the libretto for this opera on Kālidāsa's play, which he probably knew through one or more of the three German translations that had been published by that time.[15] Schubert abandoned the work in April 1821 at the latest.[13] A short extract of the unfinished score was published in 1829.[15] Also Václav Tomášek left an incomplete Sakuntala opera.[16]

New adaptations and editions

Kālidāsa's Shakuntala was the model for the libretto of Karl von Perfall's first opera, which premièred in 1853.[17] In 1853 Monier Monier-Williams published the Sanskrit text of the play.[18] Two years later he published an English translation of the play, under the title: Śakoontalá or The Lost Ring.[5] A ballet version of Kālidāsa's play, Sacountalâ, on a libretto by Théophile Gautier and with music by Ernest Reyer, was first performed in Paris in 1858.[16][19] A plot summary of the play was printed in the score edition of Karl Goldmark's Overture to Sakuntala, Op. 13 (1865).[16] Sigismund Bachrich composed a Sakuntala ballet in 1884.[16] Felix Weingartner's opera Sakuntala, with a libretto based on Kālidāsa's play, premièred the same year.[20] Also Philipp Scharwenka's Sakuntala, a choral work on a text by Carl Wittkowsky, was published in 1884.[21]

Bengali translations:

- Shakuntala (1854) by Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar

- Shakuntala (1895) by Abanindranath Tagore

Tamil translations include:

- Abigna Sakuntalam (1938) by Mahavidwan R.Raghava Iyengar. Translated in sandam style.

Felix Woyrsch's incidental music for Kālidāsa's play, composed around 1886, is lost.[22] Ignacy Jan Paderewski would have composed a Shakuntala opera, on a libretto by Catulle Mendès, in the first decade of the 20th century: the work is however no longer listed as extant in overviews of the composer's or librettist's oeuvre.[23][24][25][26] Arthur W. Ryder published a new English translation of Shakuntala in 1912.[27] Two years later he collaborated to an English performance version of the play.[28]

Alfano's opera

Italian Franco Alfano composed an opera, named La leggenda di Sakùntala (The legend of Sakùntala) in its first version (1921) and simply Sakùntala in its second version (1952).[29]

Further developments

Chinese translation:

- 沙恭达罗 (1956) by Ji Xianlin

Fritz Racek's completion of Schubert's Sakontala was performed in Vienna in 1971.[15] Another completion of the opera, by Karl Aage Rasmussen, was published in 2005[30] and recorded in 2006.[14] A scenic performance of this version was premièred in 2010.

Norwegian electronic musician Amethystium wrote a song called "Garden of Sakuntala" which can be found on the CD Aphelion. According to Philip Lutgendorf, the narrative of the movie Ram Teri Ganga Maili recapitulates the story of Shakuntala.[31]

In Koodiyattam, the only surviving ancient Sanskrit theatre tradition, performances of Kālidāsa's plays are rare. However, legendary Kutiyattam artist and Natyashastra scholar Nātyāchārya Vidūshakaratnam Padma Shri Guru Māni Mādhava Chākyār has choreographed a Koodiyattam production of The Recognition of Sakuntala.[32]

A production directed by Tarek Iskander was mounted for a run at London's Union Theatre in January and February 2009. The play is also appearing on a Toronto stage for the first time as part of the Harbourfront World Stage program. An adaptation by the Magis Theatre Company featuring the music of Indian-American composer Rudresh Mahanthappa had its premiere at La MaMa E.T.C. in New York February 11–28, 2010.

Notes

- ↑ Quinn, Edward (2014). Critical Companion to George Orwell. Infobase Publishing. p. 222. ISBN 1438108737.

- ↑ Sheldon Pollock (ed., 2003) Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia, p.79

- ↑ Stephan Hillyer Levitt (2005), "Why Are Sanskrit Play Titles Strange?" (PDF), Indologica Taurinensia: 195–232, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22

- 1 2 Jones 1789.

- 1 2 Monier-Williams 1855.

- ↑ Apte, Vaman Shivaram (1959). "भरतः". Revised and enlarged edition of Prin. V. S. Apte's The practical Sanskrit-English dictionary. Poona: Prasad Prakashan.

- ↑ Review of Figueira's Translating the Orient: The Reception of Sakuntala in Nineteenth-Century Europe at the complete review website.

- 1 2 3 Evison 1998, pp. 132–135.

- ↑ Jones 1791.

- ↑ Jones 1803.

- ↑ Figueira 1991, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Mueller, Max A History Of Ancient Sanskrit Literature

- 1 2 3 Manuela Jahrmärker and Thomas Aigner (editors), Franz Schubert (composer) and Johann Philipp Neumann (librettist). Sacontala (NSE Series II Vol. 15). Bärenreiter, 2008, p. IX

- 1 2 Margarida Mota-Bull. Sakontala (8 june 2008) at www

.musicweb-international .com - 1 2 3 Otto Erich Deutsch, with revisions by Werner Aderhold and others. Franz Schubert, thematisches Verzeichnis seiner Werke in chronologischer Folge. (New Schubert Edition Series VIII: Supplement, Vol. 4). Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1978. ISBN 9783761805718, pp. 411–413

- 1 2 3 4 Boston Symphony Orchestra Twenty-Third Season, 1903–1904: Programme – pp. 125–128

- ↑ Allgemeine Zeitung, No. 104 (Thursday 14 April 1853): p. 1662

- ↑ Monier-Williams 1853.

- ↑ Gautier 1858.

- ↑ Hubbard, William Lines (1908). Operas, Vol. 2 in: The American History and Encyclopedia of Music. Irving Squire, p. 418

- ↑ § "Works without Opus Number" of List of works by Philipp Scharwenka at IMSLP website

- ↑ Felix Woyrsch – Werke at Pfohl-Woyrsch-Gesellschaft website

- ↑ Riemann, Hugo (editor). Musik-Lexikon, 7th edition. Leipzig: Hesse, 1909, p. 1037

- ↑ List of works by Ignacy Jan Paderewski at IMSLP website

- ↑ Małgorzata Perkowska. "List of Works by Ignacy Jan Paderewski" in Polish Music Journal, Vol. 4, No. 2, Winter 2001

- ↑ Catulle Mendès at www

.artlyriquefr .fr - ↑ Ryder 1912.

- ↑ Holme & Ryder 1914.

- ↑ Background to the opera from The Opera Critic on theoperacritic.com. Retrieved 8 May 2013

- ↑ Sakontala (score) at Edition Wilhelm Hansen website

- ↑ Ram Teri Ganga Maili Archived 2011-12-28 at the Wayback Machine. at Notes on Indian popular cinema by Philip Lutgendorf

- ↑ Das Bhargavinilayam, Mani Madhaveeyam"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2008-02-15. (biography of Guru Mani Madhava Chakyar), Department of Cultural Affairs, Government of Kerala, 1999, ISBN 81-86365-78-8

References

| Sanskrit Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abhijñānaśākuntalam. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Abhijñānaśākuntalam |

- Evison, Gillian (1998). "The Sanskrit Manuscripts of Sir William Jones in the Bodleian Library". In Murray, Alexander. Sir William Jones, 1746-1794: A Commemoration. Oxford University Press. pp. 123–142. ISBN 0199201900.

- Figueira, Dorothy Matilda (1991). Translating the Orient: The Reception of Sakuntala in Nineteenth-Century Europe. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0327-3.

- Gautier, Théophile (1858). Sacountalâ: ballet-pantomime en deux actes, tiré du drame indien de Calidasá. Paris: Vve Jonas. Other on-line version: Project Gutenberg

- Holme, Garnet; Ryder, Arthur W. (1914). Shakuntala: An acting version in three acts. Berkeley: University of California Press. Other on-line versions: Hathi Trust – Hathi Trust

- Jones, William (1789). Sacontalá or The Fatal Ring: An Indian Drama by Cálidás, Translated From the Original Sanskrit and Prakrit. Calcutta: J. Cooper. On-line versions:

1792 (3rd. ed., London): Internet Archive

1807 (pp. 363–532 in Vol. 9 of The Works of Sir William Jones, edited by Lord Teignmouth, London: John Stockdale): Frances W. Pritchett (Columbia University)- Jones, William (1791). Sakontala oder der entscheidende Ring. Translated by Forster, Georg. Mainz: Fischer.

- Jones, William (1803). Sacontala, ou l'Anneau fatal. Translated by Bruguière, Antoine. Paris: Treuttel et Würtz.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1853). Śakuntalá, or: Śakuntalá Recognised by the Ring, a Sanskrit Drama, in Seven Acts, by Kálidása; The Devanágarí Recension of the Text (1st ed.). Hertford: Stephen Austin. Other on-line versions: Internet Archive – Internet Archive – Google Books – Hathi Trust

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1876). Śakuntalā, a Sanskrit Drama, in Seven Acts, by Kālidāsa: The Deva-Nāgari Recension of the Text (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Other on-line versions: Internet Archive – Internet Archive – Internet Archive – Google Books – Hathi Trust

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1855). Śakoontalá or The Lost Ring: An Indian Drama Translated Into English Prose and Verse, From the Sanskṛit of Kálidása (1st ed.). Hertford: Stephen Austin. OCLC 58897839. Other on-line versions: Hathi Trust

1856 (3rd ed.): Internet Archive – Google Books – Hathi Trust

1872 (4th ed., London: Allen & Co.): Internet Archive – Google Books – Google Books – Google Books

1885 (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co.): Internet Archive – Hathi Trust – Hathi Trust – Johns Hopkins

1895 (7th ed., London: Routledge): Internet Archive- Monier-Williams, Monier (1898). Śakoontalá or The Lost Ring: An Indian Drama Translated Into English Prose and Verse, From the Sanskṛit of Kálidása (8th ed.). London: Routledge. Other on-line versions: Project Gutenberg

- Ryder, Arthur W. (1912). Kalidasa: Translations of Shakuntala and Other Works. London: J.M. Dent & Sons. Other on-line versions:

1920 reprint: Internet Archive – Online Library of Liberty

1928 reprint: Project Gutenberg

2014 (The Floating Press, ISBN 1776535138): Google Books templatestyles stripmarker in|postscript=at position 294 (help)