Abbey of St Victor, Marseille

.jpg)

The Abbey of Saint Victor is a late Roman former monastic foundation in Marseille in the south of France, named after the local soldier saint and martyr, Victor of Marseilles.

History

Tradition holds that in about 415, John Cassian founded two monasteries of St. Victor at Marseille, one for men (the later Abbey of St. Victor), the other for women. While Cassian certainly started monastic life in Marseille, he is probably not the founder of the abbey, as the archaeological evidence of Saint Victor only goes back to the end of the 5th century. Tradition also has it that it contains the relics of the eponymous martyr of Marseille from the 4th century. In reality, the crypts preserve highly valuable archaeological evidence proving the presence of a quarry exploited in Greek times.[1] In the 5th century the monastery of St. Victor and the church of Marseille were greatly troubled by the Semipelagian heresy, that began with certain writings of Cassian, and the layman Hilary and Saint Prosper of Aquitaine begged Saint Augustine and Pope Celestine I for its suppression.[2]

In the 8th or 9th centuries both monasteries were destroyed by the Saracens, either in 731 or in 838, when the then abbess Saint Eusebia was martyred with 39 nuns. The nunnery was never re-established. In 977, monastic life began again, due to bishop Honorat and the first Benedictine abbot Wilfred who submitted the abbey to the rule of Saint Benedict.[1] It soon recovered, and from the middle of the 11th century its renown was such that from all points of the south appeals were sent to the abbots of this church to restore the religious life in decadent monasteries.[2]

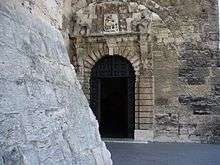

Saint Isarn (d. 1048), a Catalan monk successor as abbot to Saint Wiffred, began extensive building. He constructs the first upper church to which the tower belongs (called Isarn tower), today the access to the church.[1] Isarn was instrumental by his intercession with Ramon Berenguer I, Count of Barcelona, in obtaining the release from Moorish captivity of the monks of Lérins Abbey. Blessed Bernard, abbot of St. Victor from 1064 to 1079, was one of the two ambassadors delegated by Pope Gregory VII to the Diet of Forchheim, where the German princes deposed Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor. He was seized by one of the partisans of Henry IV and passed several months in prison. Gregory VII also sent him as legate to Spain and in reward for his services exempted St. Victor's from all jurisdiction other than that of the Holy See.

The abbey long retained contact with the princes of Spain and Sardinia and even owned property in Syria. The polyptych of Saint Victor, compiled in 814, the large chartulary (end of the 11th and beginning of the 12th century), and the small chartulary (middle of the 13th century), containing documents from 683 to 1336, make it possible to understand the important economic rôle of this great abbey in the Middle Ages.[2]

Blessed Guillaume Grimoard, who was made abbot of St. Victor's on 2 August 1361, became pope in 1362 as Urban V. He enlarged the church and surrounded the abbey with high crenellated walls. He also granted the abbot episcopal jurisdiction, and gave him as his diocese the suburbs and villages south of the city. Urban V visited Marseille in October 1365, consecrated the high altar of the church. He returned to St. Victor's in May 1367, and held a consistory in the abbey.

The abbey began to decline after this, especially from the early 16th century, when commendatory abbots acquired authority.

The loss of the important library of the Abbey of St. Victor, undocumented as it is, can probably be ascribed to the abuses of the commendatory abbots. The library's contents are known through an inventory of the latter half of the 12th century, and it was extremely rich in ancient manuscripts. It seems to have been dispersed in the latter half of the 16th century, probably between 1579 and 1591. It has been conjectured[3] that when Giuliano di Pierfrancesco de' Medici was abbot, from 1570 to 1588, he broke up the library to please Catherine de' Medici, and it is very likely that all or many of the books became the property of the king.

In 1648 the échevins (municipal magistrates) of Marseille petitioned Pope Innocent X to secularise the monastery, because of the unsatisfactory behaviour of the monks. The Pope was not willing to do so, but instead had the abbey taken over by the reformist Congregation of Saint Maur. Thomas le Fournier (1675–1745), monk of St. Victor's, left numerous manuscripts which greatly assisted them in their publications.[4]

However, the behaviour of the monks generally did not improve, and after their abysmal showing during the plague of 1720, during which they barricaded themselves inside their walls instead of providing any assistance to the stricken, Pope Benedict XIII secularised the monastery in 1726, converting it into a collegiate church with a community of lay canons under an abbot.[5] This was confirmed by a bull of Pope Clement XII dated 17 December 1739.[6].

In 1774, it became by royal decree a noble chapter, the members of which had to be Provençals with four noble descents; from this date they bore the title of "chanoine comte de Saint-Victor".[7]

The last abbot of Saint-Victor was Prince Louis François Camille de Lorraine Lambesc. He died in 1787 and had not yet been replaced at the outbreak of the Revolution.[8]

Buildings

In 1794 the abbey was stripped of its treasures. The relics were burned, the gold and silver objects were melted down to make coins and the building itself became a warehouse, prison and barracks. All that now remains of the abbey is the church of St. Victor, dedicated by Pope Benedict IX in 1040 and rebuilt in 1200. The abbey was again used for worship under the First Empire and restored in the 19th century. The church was made into a minor basilica in 1934 by Pope Pius XI.[1]

The remains of Saint John Cassian were formerly in the crypt, with those of Saints Maurice, Marcellinus and Peter, the body of one of the Holy Innocents, and Bishop Saint Maurontius.[9]

See also

- Santa Maria, Uta, a church founded by St. Victor's monks

References

- 1 2 3 4 Marseille Office of Tourisme

- 1 2 3 Goyau, Georges. "Marseilles (Massilia)." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 3 Jun. 2013

- ↑ by M. Morhreuil

- ↑ Augustin Fabre, Les rues de Marseille, édition Camoin, Marseille, 1869, 5 volumes, tome V, p. 457

- ↑ Paul Gaffarel et de Duranty, La peste de 1720 à Marseille & en France, librairie académique Perrin, Paris, 1911, p. 172.

- ↑ Mylène Violas, "Des moines bénédictins aux chanoines-comtes: aux origines de la sécularisation de l’abbaye de Saint-Victor", in Bicentenaire de la paroisse Saint-Victor, actes du colloque historique (18 October 1997), La Thune, Marseille, 1999, p. 26, ISBN 978-2-84453-003-5

- ↑ Paul Masson in Encyclopédie départementale des Bouches-du-Rhône, Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône, Marseille, 17 volumes 1913 & ndash; 1937, tome III, p. 846

- ↑ André Bouyala d’Arnaud, Évocation du vieux Marseille, les éditions de minuit, Paris, 1961, p. 117

- ↑ The biography of Saint Izarn, abbot of St. Victor in the eleventh century (Acta SS., 24 Sept.), gives an interesting account of his first visit to the crypt.

Sources

- M. Fixot, J.-P. Pelletier, Saint-Victor de Marseille. Étude archéologique et monumentale, Turnhout, 2009, ISBN 978-2-503-53257-8, 344 p., 220 x 280 mm, Paperback

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abbaye Saint-Victor. |

External links

- Marseille-Tourisme.com Abbaye Saint Victor (in French)

![]()