Though weaker than the best of Restoration comedies, early 18th century British comedy features some strong works.

John Gay

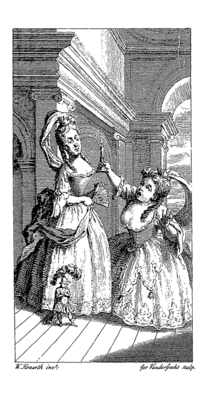

John Gay (1685-1732) wrote one of the best comedies of the early 18th century, "The beggar's opera" (1728), a rough satire of robbers and law agents secretly protecting robbers and profiting by their robberies. In the opinion of Knight (1962), the play “celebrates a union between merriment and horror” (p 175). Thievery is self-justified. “We are for the just partition of the world, for every man hath a right to enjoy life,” Ben Budge, one of Macheath’s henchmen, declares. The play draws ire from representatives "of traditional values, the enemy of anarchy and all threatening innovations, the friend of conservative censorship: the Moral Majority...The issue was always the attractiveness of Gay's highwayman, and Gay's failure to hang him at the end" (Bentley, 1982 p 19).

Critics emphasize Gay’s success in showing similarities between high life and low life. "The manners of the upper social world are shown to be in complete harmony with the under world. When it is found that Polly Peachum had married the highwayman Macheath 'for love', her outraged mother faints with the words 'I thought the girl had been better bred.' The whole episode is in the manner of the conventional family scene over an erring daughter but with the ideas absolutely reversed" (Reynolds, 1921 p 231). “Peachum's co-rival, Lockit, the prison warden, who, like Peachum, carries about an account book, includes himself in this system and, by likening himself first to an inn-keeper and then a tailor, extends it. He greets Captain Macheath, who has just been arrested, as ‘a lodger of mine’, enforcing the figure by demanding ‘Garnish, captain, garnish.’ And in finding the ‘fittest’ fetters for him, becoming more-and-more accommodating in getting just the right fit as the captain pays more-and-more money, he becomes almost indistinguishable from his commercial counterpart: 'How genteely they are made!- They will fit as easy as a glove.' Dealers in salvation, in justice, in freedom, in power, even in death are recognized, like those in goods, by the denizens of this world as 'honest' professionals. Peachum and Filch agree, for instance, that their profession and that of medicine are equally beholden for opportunities of remunerative employment to women. Macheath asserts that for recruiting such women to the ranks of ‘free-hearted ladies’, ‘the town perhaps hath been as much oblig'd to me...as to any recruiting officer in the army.' And, before actually joining these ranks himself as the free-handed admirer of women, he likens his particular devotion to Polly to that of a courtier for a pension or of a lawyer for a fee- figures of speech that Polly apparently finds assuring. Love and lovers are generally included, along with husbands and wives, in this metaphorical stew. Males are likened to thieves, perjurers, and courtiers; females- when not simply reduced to free or saleable 'whores', 'sluts', 'hussies', and 'wenches'- are likened to lawyers, who must 'be fee'd into our arms', to smugglers, to tradesmen, and thieves. Macheath's doxies, however, even while conducting a commercial seminar, evidently appropriate, indeed, to whores, sluts, and thieves, carefully maintain the polite forms of address: they are all like ladies, that is to say, and like ladies all the time. The actual thieves of Macheath's gang are, similarly, like gentlemen except when they observe, somewhat sourly, the similarity between gentlemen and gamesters" (Piper, 1988 pp 337-338).

As for Macheath, “upon this part Hazlitt expends all the wealth of his discernment. Macheath, he says, is not a gentleman but a ‘fine gentleman’. His manners should resemble those of this kidney as closely as the dresses of the ladies in the private boxes resemble those of the ladies in the boxes which are not private. He is to be one of God Almighty's gentlemen, not a gentleman of the black rod. His gallantry and good breeding should arise from impulse, not from rule; not from the trammels of education, but from a soul generous, courageous, good-natured, aspiring, amorous. The class of the character is very difficult to hit. It is something between gusto and slang, like port wine and brandy mixed. It is not the mere gentleman that should be represented but the blackguard sublimated into the gentleman...Filch is a serious, contemplative, conscientious character. He is to sing 'Tis woman that seduces all mankind' as if he had a pretty girl in one eye and the gallows in the other...The characters in the Opera are to have but a superficial air of gallantry and romance; there should be something hang-dog about them...Gay seems to have glossed over the real nature of the intrigue. It was, doubtless, always a delicate thing to suggest to English ears, even in the eighteenth century, that Peachum 'père et mère' have a vested interest in Polly's wantonness, and a legitimate grievance in her revolt in favour of a single lover. ‘Look ye, wife,' says Peachum, 'a handsome wench in our way of business is as profitable as at the bar of a Temple coffee-house, who looks upon it as her livelihood to grant every liberty but one'” (Agate, 1922 pp 147-150).

"The beggar's opera"

Time: 1720s. Place: London, England.

Text at http://www.bibliomania.com/0/6/2/1088/frameset.html https://archive.org/details/britishdramaaco03unkngoog http://www.bartleby.com/202/ https://archive.org/details/britishtheatre11bell

Peachum is at the same time head of organized crime and one who profits from bribes when criminals are caught. When Mrs Peachum informs him of a possible love-match between the leader of a band of robbers, Captain Macheath, and his daughter, Polly, he is alarmed. "Gamesters and highwaymen are generally very good to their whores, but they are very devils to their wives," he says. Polly tries to reassure him, but is interrupted by Mrs Peachum, who has discovered she is already married to Macheath. "Can you support the expense of a husband, hussy, in gaming, drinking, and whoring?" she asks. The parents decide to arrange for Macheath's capture and execution by the law, but Polly discovers the plan and warns Macheath that her father is preparing evidence against him. To counter this, he proposes a plan to his band of outlaws. "Make him believe I have quitted the gang, which I can never do but with life," he suggests. "At our private quarters I will continue to meet you. A week or so will probably reconcile us." However, one of his mistresses, Jenny Diver, jealous of Polly, helps Peachum capture him. "You must now, sir, take your leave of the ladies," Peachum says laconically. "And, if they have a mind to make you a visit, they will be sure to find you at home." At Newgate prison, Lucy Lockit, daughter of the jailor and pregnant with Macheath's seed, rails against him. "How can you look me in the face after what hath passed between us?" she asks him. "See here, perfidious wretch, how I am forced to bear about the load of infamy you have laid upon me! Oh, Macheath, thou hast robbed me of my quiet. To see thee tortured would give me pleasure." When he denies being married to Polly, she softens. Meanwhile, Lockit and Peachum agree to go halves in his execution. Lockit declares to his daughter: "Look ye, there is no saving him. So I think you must even do like other widows - buy yourself weeds and be cheerful." But Lucy refuses until interrupted by Polly's arrival, whose bad timing Macheath curses. Both women rage and complain: Polly: "Oh, how I am troubled!" Lucy: "Bamboozled and bit!" then turn against each other. Peachum takes his daughter away while Lucy steals her father's keys, permitting Macheath to escape, which disappoints the father. "If you would not be looked upon as a fool, you should never do anything but upon the foot of interest. Those that act otherwise are their own bubbles," he says to her. "You shall fast and mortify yourself into reason, with now and then a little handsome discipline to bring you to your senses." Lucy intends to do more: poison Polly, but is unable to. Both women grieve to find Macheath recaptured. Lockit consoles his daughter. "Macheath’s time is come, Lucy," he says. "We know our own affairs; therefore, let us have no more whimpering or whining," as does Peachum to his: "Set your heart at rest, Polly. Your husband is to die today." In the condemned hold, both women mourn for him, but are abashed when seeing four more women appear with babes in arms, all Macheath's, so that he now prefers to be executed than face them all. But because the day of execution falls on a holiday, he is reprieved and reunited with Polly.

George Farquhar

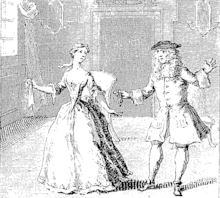

George Farquhar (1677-1707) achieved comic brilliance with "The beaux' stratagem" (1707), offering sparkling wit in a manner reminiscent of Etheredge. Farquhar also wrote three other comedies: "The constant couple" (1699), "The twin rivals" (1702), and "The recruiting officer" (1706). In "The constant couple", Lady Lurewell loved Captain Standard in her youth but, being frustrated in her design of marrying him, acquires a hatred of all men until she is reunited with him.

"The beaux' stratagem" "is full of the freshest humour, and if acted at all respectably must entertain. There is nothing more exhilarating, and the characters and incidents come back on us with a perpetual pleasure. We find ourselves thinking with a smile of Scrub, and the presumed London servant whom he so admires. It is extraordinary how Goldsmith later caught the same freshness of handling in She Stoops to Conquer" (Fitzgerald, 1882 vol 1 pp 184-185). Morris (1882) exclaimed: "What a play it is! How full of life and spirits! What gaiety and invention in the plot! What animation and variety in the characters! What ease, brightness, and resource in the language! For audacity and effect the final scene between Mrs Sullen and her sottish husband has no parallel save in that incomparable one between the two sisters in Congreve's Love for Love" (p 142).

Nettleton (1914) preferred Etherege's "The Beaux' stratagem" over Restoration comedy, the former showing "both the traditions of Restoration comedy and the advent of new tendencies. Here are present in full force the familiar flings of the beau monde at the country, and yet something of real country atmosphere; French characters and phrases, and yet a hearty English element; much of the immorality of earlier comedy, with some of the later improvement in moral tone. Though Squire and Mrs Sullen separate at the end with scant regard for the marriage tie, Farquhar does not scoff at virtue and exalt vice in Wycherley's fashion. The seeming intrigue between Mrs Sullen and Count Bellair is only her scheme to solve her matrimonial troubles. Instead of trying to deceive her husband, she has him brought to her rendezvous with the count. As the count says, when Mrs Sullen shows him that she has not taken his advances seriously: 'Begar, madam, your virtue be vera great, but garzoon, your honeste be vera little.' The dialogue is bright, witty, and vigorous. Mrs Sullen, who epitomizes her husband as 'a sullen, silent sot' breaks out with these words:'Since a woman must wear chains, I would have the pleasure of hearing 'em rattle a little.' (II,i) Archer and Cherry have some excellent passages. Though Mrs Sullen's long speeches (II,i) voice the usual contempt of the town for the country, the play has genuine country atmosphere. The countrywoman who comes to Lady Bountiful to have her husband's leg cured is given, in fact, some dialectic forms of speech 'mail' for 'mile' and 'graips' for 'gripes' (IV,i). Scenes with the landlord, the tavern maid, and the highwaymen come as a relief from the ceaseless intrigues of fashionable London. The plot construction is highly ingenious, especially in the very effective last act. Archer- whose name is sufficiently explained by Boniface's words (II,3),'You're very arch'- justifies his name by replacing the French count at the rendezvous, and obtains entrance to Mrs Sullen's chamber. This leads to a situation familiar in Restoration comedy in such scenes as Vanbrugh's, where Loveless carries off Berinthia (The Relapse,IV,3), and Farquhar's own scene in his 'Love and a bottle', where Roebuck invades Lucinda's chamber. But the ingenuity with which a stock situation is rescued from the relentless issue in Vanbrugh is Farquhar's own. The attempted robbery not merely interrupts the amour at the critical point, but offers an effective chance for Archer to display his bravery and to merit Mrs Sullen's regard. Mrs Sullen herself well describes him: 'The devil's in this fellow! he fights, loves, and banters, all in a breath.' (V,4) The next scene is full of rapid movement of plot and shift of situation. The whole act, handled with vigorous assurance, is of sustained interest. Farquhar is to some extent a forerunner of Goldsmith. The opening conversation between Boniface, the innkeeper, and Aimwell and Archer about the menu is quite like that of Mr Hardcastle, the supposed innkeeper, with Marlow and Hastings in 'She stoops to conquer'. There is something, too, in the freshness of atmosphere, in the group of country and inn folk, and in the Irish good-humour, which is akin to the spirit of Goldsmith. Whatever Farquhar's lapses in point of morality, he has none of Wycherley's vindictive and brutal cynicism. Most of his characters, with all their faults, are companionable. They are not so clever as Congreve's, but fertile brains and facile manners make them attractive, despite some heartless traits" (Nettleton, 1914 pp 137-140).

In Hume's 1990 report of marital discord in English comedy from Dryden to Fielding, "the only one of these plays to propose 'divorce' as a really happy solution is The Beaux Stratagem...Sullen is a stupid, brutish sot, who is made thoroughly unattractive in the course of the play. In an amusing inversion of a proviso scene, the Sullens agree only that they have no use for each other. He is delighted at the thought of being rid of her but intends to keep her marriage portion- changing his mind only when he has to yield to blackmail...This is of course entirely illegal all around. The Sullens lack grounds even for a separation, and only parliamentary decree (for which there is no legal justification) could allow either to remarry, though most readers find a clear implication that Mrs Sullen will marry Archer. Yet this flight into the completely unreal has seemed attractive and satisfying to generation after generation of play-goers. There has been scarcely a whisper of protest about illegality, immorality, sentimentality, or what have you...Farquhar's wishful thinking is grounded in logic and serious argument: his indebtedness to Milton, as suggested long ago. However illegal, this solution is highly agreeable and accords with our idea of what 'ought' to be. The lack of outcry about impossibility and immorality suggests the need for caution in assuming that realism- always a vexed issue in these plays- was expected by the audience" (pp 265-266).

Dobrée (1924) approved Hazlitt's general opinion of Farquhar's plays: "'He makes us laugh from pleasure oftener than from malice...There is a constant ebullition of gay, laughing invention, cordial good-humour, and fine animal spirits in his writings. It is for that we should go to Farquhar. If we search for a poet, for a profound critic of life, for a close thinker of the Restoration type, or for a finished artist, we shall not find him. To approach him for a torrent of semi-nonsensical amusement, mingled with that clear logic which also is the Irishman's heritage, and to ask no more, is to obtain a refreshing release from the conditioned social universe in which we are forced to live" (p 169).

"The beaux' stratagem"

Time: 1700s. Place: Lichfield, England.

Text at http://www.bibliomania.com/0/6/87/1879/frameset.html http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/37195 https://archive.org/details/britishdramaaco03unkngoog http://fadedpage.com/showbook.php?pid=20110812

Alternating in their roles between master and servant from town to town, Aimwell and Archer, fortune-hunters, arrive where Mrs Sullen complains to her sister-in-law, Dorinda, of her husband's ill treatment, a man often arriving drunk at four in the morning and sullen all day. In Mrs Sullen's view, "there’s no form of prayer in the liturgy against bad husbands". Though her dowry brought him 10,000 pounds, Squire Sullen has become "a sad brute". But perhaps she can can change her husband by making him jealous of Count Bellair. Meanwhile, Gibbet, seemingly an officer-of-the-law but in reality a robber, converses with the innkeeper, Boniface, who reveals that he may have detected criminals in the house. When asked how he could guess, Boniface answers: "Why, the one is gone to church," to which Gibbet retorts: "That’s suspicious, I must confess." As the true fortune-hunter he is, Archer woos Boniface's daughter, Cherry, who quickly proposes marriage. She says she will bring him 2,000 pounds, in reality 200 pounds entrusted to her by Gibbet. On seeing Dorinda at church, Aimwell, true fortune-hunter that he is, "read her thousands in her looks, she looked like Ceres in her harvest..." Mrs Sullen and Dorinda approach Archer to learn more about Aimwell, following which Mrs Sullen arranges to have her husband overhear Count Bellair's attempts at seducing her. To Count Bellair she admits herself to be "a prisoner of war". As Bellair gets bolder, Squire Sullen advances with drawn sword; to protect the count, his wife draws a pistol, informing her husband that all this was done for the benefit of making him jealous. Meanwhile, Archer calls on Lady Bountiful, mother to Mrs Sullen, to aid Aimwell, pretending to have been taken ill near the gate of her house. Aimwell is brought in by Dorinda and presses her hand hard, which Lady Bountiful ascribes to "the violence of his convulsion". Aimwell courts Dorinda in such a manner that she begins to daydream: "if I marry my Lord Aimwell," she tells herself, "there will be title, place, and precedence, the park, the play, and the drawing-room, splendour, equipage, noise, and flambeaux.— Hey, my Lady Aimwell’s servants there!— Lights, lights to the stairs!— My Lady Aimwell’s coach put forward!— Stand by, make room for her ladyship!— Are not these things moving?" to which Mrs Sullen is moved to weep. That night, Archer comes out of Mrs Sullen's closet and takes her by the hand, but she is unable to fulfill his wishes, declaring: "I am a woman without my sex." Instead, she cries out. As a result, Scrub, her servant, shouts loudly that thieves have entered the house, whereby she now clings to Archer for protection. When Gibbet enters, Archer takes him prisoner and with the help of Aimwell rescues Lady Bountiful and Dorinda from Gibbet's henchmen. When Archer presses Mrs Sullen for his reward, he is interrupted by the arrival of Mrs Sullen's brother, Charles. Meanwhile, Aimwell is set to carry off Dorinda but feels constrained by her goodness to admit he is "no lord, but a poor, needy man". Not so, for Charles brings word that Aimwell's brother is dead and so Aimwell is now the lord of a large estate. For his part, Archer obtains half of his wife's fortune and a letter from Cherry stating that her father, in league with the house-thieves, has escaped, but not before she secured his money and more. In view of his sister's unhappy marriage, Charles proposes a separation with her husband, which both agree on, with Sullen losing her fortune at the hands of Archer, who delivers his stolen papers to Bellair.

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (1707-1754) wrote two comedies of note: "The modern husband" (1732) and "Tom Thumb the great" (1731).

Banerji (1929) with a puritan-mindedness as ugly as unsparing commented that "The modern husband" "is much to the credit of the audience that the chief objection to the play was the sordid scenes in which Fielding dwells on his main theme, the selling of the wife, Mrs Modern, to the noble voluptuary, Lord Richly, by the husband. The woman who plays her part so willingly in the affair, the husband who helps her without any hesitation to degrade herself to the lowest depths, the rich voluptuary who is so thoroughly convinced that every woman has her price and acts accordingly, are all portrayed with a realism which is as ugly as it is unsparing” (p 37). Fielding presents wife selling "not an image he builds up to as a shocking instance of the immorality that may exist within marriage; Fielding presents it as an occurrence and indicative of widespread social vice...The conflict of values-family and honor versus money-is evident throughout the play; however, it appears to be a conflict honor is losing. There is little talk of defending one's honor. Mostly, the characters speak of litigation, payment, and profit" (Wilputte, 1998 pp 457-458)

"Most entertaining of Fielding's early dramatic work is 'Tom Thumb'...This admirable burlesque hits such vulnerable parts of regular tragedy as its conventional opening passages, its heroic themes of love and valour, its pompous phrases and artificial rhymed similes. The tragedy Ghost passes from the sublime to the ridiculous in the apparition of Tom Thumb's dead father, the classical sonority of Thomson's 'Oh, Sophonisba, Sophonisba, oh' is parodied in 'Oh! Huncamunca, Huncamunca, oh!' and the solution by massacre is outdone by half-a-dozen consecutive murders in as many lines, followed by the suicide of the king. Not merely contemporary tragedy but dramatic criticism is burlesqued" (Nettleton, 1914 p 215). Knight (1981) emphasized resemblances in style between Fielding and Aristophanes. 'In 'Thesmophoriazusae' Euripides' father-in-law, implausibly disguised as a woman, is taken prisoner by the anti-Euripidean women celebrating the Thesmophoria (an exclusively female feast of Demeter). Euripides seeks to rescue him by enacting various rescue scenes from his own plays. Here, as in Tom Thumb, the tragic mode is directed to a ridiculous subject" (489-490). “The many extravagances of the heroic dramatists are ridiculed with a satiric power and ingenuity that appear to be inexhaustible, and there is hardly a line in the play that does not make an effective hit at the bombast and rant in the mighty lines of Dryden, Banks, Lee, Thomson, and other exponents of the heroic drama. From the opening rhapsody of the courtier, Doodle, on the auspicious day of Tom Thumb’s triumph, a day which ‘all nature wears one universal grin’, to the last words...in which the dying king likens the tremendous debacle at the end to the kings, queens, and knaves in a pack of cards throwing each other down till the whole pack lies scattered and o’erthrown’, we have a rich succession of burlesque declamations, heroic outbursts of tragic or tender passion, and mock heroic similes and for almost every line Fielding refers us to a passage in some heroic tragedy well known to the playgoers of his time” (Banerji, 1929 p 23).

"The modern husband"

Time: 1730s. Place: London, England.

Text at https://archive.org/details/workshenryfield09fielgoog

To extort money from him, Modern has long permitted his wife, Hillaria, to sleep with Lord Richly, but since the wealthy man's passion has diminished, he proposes to plant witnesses to their adultery and thereby recover even more money. She refuses because this would ruin her reputation. Instead, she requests 100 pounds from her second lover, Bellamant, ill at ease at being forced to ask his wife for that exact amount he gave her on the previous day. Their talk is interrupted by the arrival of Richly's nephew, Gaywit, in love with the Bellamants' daughter, Emilia, though obligated by the settlement of his uncle's estate to marry his daughter, Charlotte, who shows no interest in him and is courted by the Bellamants' son, a captain in the army. Even after obtaining Bellamant's note, Hillaria is forced to accept Richly's offer of helping him obtain a new mistress: Bellamant's wife. Richly wins the 100 pound note from Hillaria at cards but gives it by design to Mrs Bellamant when he deliberately loses at cards with her. When Bellamant aks his wife for more money, he recognizes the 100 pound note and wonders how it could have returned in her hands. Intent on ruining his wife's reputation to escape with him from their respective spouses and at the same time help out Richly's purpose, Hillaria suggests to Bellamant that she obtained the note from Richly. Struck by strong feelings of jealousy, Bellamant agrees to Hillaria's proposal of witnessing in secret a meeting between the two supposed lovers. However, Hillaria and Bellamant are surprised together by Modern who rages in the presence of Mrs Bellamant and Richly, the latter quickly escaping from this embarassment. Filled with remorse, Bellamant admits to his wife he committed adultery with Hillaria. Despite her grief, Mrs Bellamant forgives her husband, who promptly goes over to Richly's house to warn him never to approach his wife again. Gaywit follows this unpleasant visit by asking his uncle for his consent to marry Emilia, which he obtains and she accepts. Meanwhile, Charlotte pretends not to consider seriously Captain Bellamant's proposal of marriage, but quickly changes her mind when he pretends to be interested in another woman. Abandoned by her two lovers, Hillaria attempts to keep her third, Gaywit, but he repudiates her in front of the Bellamant family to force her away to the country. "Let us henceforth be one family," Gaywit proclaims to the Bellamants and Charlotte, "and have no other contest but to outvie in love."

"Tom Thumb the great"

Time: Prehistoric England. Place: England.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/tragedyoftragedi00fielrich https://archive.is/http://www.readbookonline.net/title/42479/

King Arthur's court celebrates Tom Thumb's victory over the giants and their captive queen, Glumdalca. When the queen on the victorious side, Dollallolla, learns that Glumdalca was married to twenty men, she is envious. "O happy state of gigantism," she cries, "where husbands/Like mushrooms grow, whilst hapless we are forced/To be content - nay, happy thought with one." The king asks Tom Thumb what is his wish as a reward for such prowess. He replies he wants to marry his daughter, Huncamunca. Although finding the request "prodigiously bold", the king accepts. Loving Tom for herself, Dollallolla grows jealous of her daughter. She encourages Lord Glizzle, himself in love with Huncamunca, to foment a rebellion. While Tom walks in the streets with Noodle, a courtier and friend, they are interrupted by a bailiff and his follower who arrests Noodle for ignoring a tailor's dept. An angry Tom kills both bailiff and follower. To understand the state of Huncamunca's heart, Grizzle appears before her as a suitor. He learns the worst possible news, that the princess is enthralled by Tom Thumb's person. She confirms this to Tom's face, despite Glumdalca's attempts to attract him to her. Meanwhile, King Arthur also suffers in the throes of love. He loves Glumdalca and does not know what to do. Despite Grizzle's pleas, Huncamunca marries Tom. But on next seeing Grizzle, she wavers. "A maid like me heaven formed at least for two," she asserts. "I married him and now I'll marry you." But Grizzle refuses to share his love with Tom and so initiates rebellion in the kingdom. At court, a ghost appears in the shape of Tom's father, Gaffer, warning the king of the impending civil war and that his son will be swallowed by a red cow. Arthur's hope lies in Tom's arm. "In peace and safety we secure may stay," he declares, "while to his arm we trust the bloody fray." "He is indeed a helmet to us all," his queen agrees. A mighty battle ensues with thunder and lightning, Tom as usual supremely victorious. The elated king opens the prisons, but after learning from Noodle that Tom has been swallowed by a red cow, he shuts them again. The disappointed queen kills Noodle and is herself killed by Noodle's lover. A general melee ensues. Huncamunca kills her mother's murderer but is killed by an envious courtier, killed in turn by a jealous maid of honor, herself killed by the king, who ends the slaughter by killing himself.

Richard Steele

Another Irish-born dramatist, Richard Steele (1672-1729), wrote two pleasant comedies, "The conscious lovers" (1722), based on Terence’s “The girl from Andros” (166 BC), and “The tender husband” (1705), the latter with the collaboration of Joseph Addison (1672-1719, see below).

Doran (1888) pronounced "The conscious lovers" "excessively indecent. There is nothing worse in Aphra Behn than the remarks made by Cimberton, the 'coxcomb with reflection', on Lucinda. This fop, played by Griffin, is for winning a beauty by the rules of metaphysics. There is more pathos than humour in this comedy" (p 370). The play may more properly be said to be "sentimental in three important ways: (1) The characters move in a world within which, by implication, the power of virtue will always overcome those forces (not necessarily evil forces) opposing it; (2) The focus on the family, from the servants up to the head of the household, invariably involves a series of emotional stereotypes; and (3) Love between men and women is taken directly from the sentiment and sensibility of contemporary French romances and novels" (Novak, 1979 p 49). In "The conscious lovers", "Steele’s characters are more virtuous than the original, a crucial if not obligatory element in the lovers of the emerging genre of sentimental comedy...The novelty of the play lay less in its characters and sentiments than in its action. A mysterious improbability, Indiana’s recovery of her parent, was the foundation of the plot. Terence had used the strange circumstances of the girl’s career to strengthen the comic effect; Steele used them to intensify the emotional. In earlier sentimental comedies improbabilities were present, but not prominent. Their personages were ideal, but their action was on the whole realistic. The further development, one of the most important contributions by Steele to the type, was a natural, almost an inevitable, one. That perfectly virtuous people come to a happy issue out of all their afflictions is, alas, a theory not so plausibly illustrated in a world resembling the real one as in a realm of beneficent coincidence. In such a region the conscious lovers moved; and sentimental comedy, though still affecting truth to life, departed therefrom still further. As Steele’s method in this particular was often followed, improbability of plot became henceforth a frequent, though not a constant, attribute of the genre” (Bernbaum, 1915 pp 133-136). Nettleton (1914) also emphasized the sentimental element in "The conscious lovers". "The excellent scene where Tom recalls to Phillis his torments of love while he washed the outside of a window which she was cleaning inside is a delightful bit of foolery, an unconscious burlesque one is tempted to suggest, of the sentiment of the conscious lovers. Unhappily such byplay only partially relieves the essentially sentimental strain. More prominent are the virtuous loves of Bevil and Indiana, the moral heroics which tend to convert Bevil from hero to prig, and the tragic heartrendings of Indiana before her restoration to her long-lost father. The dialogue responds to the sentimental strain. 'If pleasure,' says Bevil (II,2), 'be worth purchasing, how great a pleasure is it to him who has a true taste of life, to ease an aching heart; to see the human countenance lighted up into smiles of joy, on the receipt of a bit of ore which is superfluous and otherwise useless in a man's own pocket?' Bevil ushers the music-master to the door with less of the instinctive courtesy of the gentleman than the complaisant condescension of the conscious prig, declaring 'we ought to do something more than barely gratify them for what they do at our command, only because their fortune is below us.' To this Indiana responds with 'a smile of approbation' and the sentiment that she 'cannot but think it the distinguishing part of a gentleman to make his superiority of fortune as easy to his inferiors as he can.' Many of the scenes conclude with moral tags in verse. Already the habit of moral aphorism had fastened itself on comedy, a habit that was to develop to great extremes before it lost its charm in the mouth of the hypocrite, Joseph Surface." "The play reaches two emotional peaks. The first comes when Myrtle goads Bevil Junior into a duel over Lucinda; he accepts the challenge when Myrtle insults Indiana's honor, but then reconsiders, composes himself, and manages to pacify his friend. The second climax comes when Mr Sealand, having taken it upon himself to determine whether Bevil Junior has been above board about Indiana, visits her and finds her convincingly chaste and well-mannered. More importantly, he recognizes her bracelet as a token he had left his infant daughter when he departed for the Indies...The joyous reunion of father and daughter leads to the resolution of the plot...The play certainly valorizes the figure of the enterprising merchant...and also lampoons antimerchant opinion by having its most absurd character, Cimberton, act dismayed that the Sealands persist in making their money by trade...It is doubtless the case that the ultimate union of Indiana and Bevil Junior means the integration of moneyed and landed interests...Bevil Junior and Indiana's love story which arises from her travails is also a story of sympathetic passion that reverberates with feelings of benevolent disinterest...From the match between Indiana and Bevil Junior— which is also a reunion of Indiana and Mr Sealand— a new unity arises. Class conflict is obviated, and love, duty, and fortune flow together...The marriage between Indiana and Bevil Junior, a relation predicated on beneficence rather than self-interest, ripples into a new arrangement that includes Lucinda and Myrtle. Myrtle testifies that ‘no abatement of fortune shall lessen her value to me,’ a sentiment welcomed by Lucinda with a hearty ‘Generous man!...now I find I love you more, because I bring you less'...Steele differentiates Cimberton's unfeeling gaze and self-interest— qualities that make him a bad political subject as well as a bad marriage partner— from Bevil Junior's mode of disinterest that can still love, sympathize, and perceive with acuity. Bevil Junior's feelings can succeed in causing men to cohere as well; the duel scene between him and Myrtle induces a poignant epiphany about homosocial feeling" (Wilson, 2012 pp 500-506). "Sealand...shows intelligence, wit, and good humor. Gentlemanly despite his lack of the proper ancestral state, he feels greater concern for his daughter's happiness in marriage than for the family background of her mate...Cimberton, a pretender to wit...easily duped by Myrtle and Tom...approaches marriage cold-bloodedly with no affection; his only response to Lucinda as opposed to her dowry is an increase in appetite when he inspects her 'like a steed at sale'" (Kenny, 1972 pp 33-35).

"Although The Tender Husband has sometimes being described by 20th century critics as sentimental, it is not...There is not true love like the young people in The Funeral, no repentance like that of The Lying Lover, no 'joy too exquisite for laughter'. Plot, characterization, and dialogue are consistently comic" (Kenny, 1972 p 29). The play "comprises a cast of influential characters. Humphry is the prototype of Goldsmith’s Lumpkin in 'She stoops to conquer' and Biddy to Sheridan’s Lydia Languish in 'The rivals' (Bateson, 1963, p 52). Bateson tastelessly considered the scene whereby Clerimont surprises his wife “unsavory in tone and makes unpleasant reading”. Netttleton (1914) was also repulsed by Clerimont's relation with his wife. "The opening scene develops Clerimont's repellant scheme of testing his wife by disguising his mistress, Fainlove, in man's attire, and the scene (V,i) where Clerimont interrupts their assignation approaches too closely the dangerous path of Restoration comedy. It may be said that Steele reunites husband and wife in the recognition that married happiness rests on constant love, but it is a doubtful ethical standard that permits the erring husband to pose as tenderly magnanimous...Far more interesting is that part of the play which concerns Biddy Tipkin and her cousin Humphry Gubbin, ancestors, in some sense, of Sheridan's Lydia Languish and Goldsmith's Tony Lumpkin. Biddy Tipkin, who 'has spent all her solitude in reading romances' and has renamed herself 'Parthenissa' is steeped in French and English romances as thoroughly as is Lydia Languish in the sentimental novels of the circulating library. Biddy's romantic humour gives rise to excellent comic scenes with Clerimont, who humours her with the fantastic language of chivalry, and with her country bumpkin cousin, who submits his intended bride to scrutiny, 'as not caring to buy a pig in a poke'. The scene (III,2) where Biddy and her cousin agree to disagree, and the aunt is led to think 'they are come to promises and protestations', is closely akin to Goldsmith's scene between Tony Lumpkin and Miss Neville where Mrs Hardcastle imagines they are billing and cooing. It is somewhat remarkable that Goldsmith and Sheridan who led so powerfully the revolt against sentimental comedy borrowed from Steele. Fielding, too, possibly found suggestions for Squire Western in Sir Harry Gubbin. On the other hand, Steele owed somewhat to Molière, to Cibber, and to Addison, while the passage (V,2) in which Tipkin insists on being written down a rascal is obviously reminiscent of Dogberry. Viewed as a whole, 'The tender husband' is perhaps Steele's most genuine comedy" (pp 101-103).

"The conscious lovers"

Time: 1720s. Place: London, England.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/consciouslovers00steegoog

Sir John Bevil has arranged for his son to marry Lucinda, daughter of a wealthy merchant, Sealand, but neither party wish to marry the other. Bevil Junior loves another, Indiana, his father's ward, but has not yet revealed his love to her in deference to his father's wish, who saved this woman from the clutches of the brother of a pirate who had kidnapped her at sea. Lucinda is loved by Myrtle, glad about Bevil Junior's promise of helping him marry her. Bevil Junior suggests that Myrtle disguise himself as a lawyer to slow down or confound Sealand's design to marry his daughter, which he readily accepts. Though loving Bevil Junior, Indiana is wholly unable to find out whether he loves her. Meanwhile, Lucinda's mother has in mind another match for her, her wealthy cousin, Cimberton, whom Lucinda abhors. To her disgust, he eyes her body with approval, lauding "the vermilion of her lips", "the pant of her bosom", "her forward chest", to which she exclaims: "The grave, easy impudence of him!" and "The familiar, learned, unseasonable puppy!" The disguised Myrtle is successful in impeding the progress of Mrs Sealand's unwelcome plan. But he is unhappy on discovering that Bevil Junior has been corresponding with Lucinda, meant to secure their agreement in not marrying. Deeply suspicious, he challenges his friend to a duel until finding out the truth. Still worried, he dons a second disguise as Cimberton's cousin, and is introduced as such to Mrs Sealand, though revealing his true self to Lucinda. Meanwhile, curious to meet Bevil Junior's charge, Sealand visits Indiana, who tells her story, in particular her frustrations in regard to her protector's ambivalence towards her. "What have I to do but sigh, and weep, to rave, run wild, a lunatic in chains, or, hid in darkness, mutter in distracted starts and broken accents my strange, strange story!" she exclaims. Sealand is stunned to discover that she is his daughter from a previous marriage, captured along with his wife by a pirate at sea. As a result, he asks his sister to run at once to young Bevil. "Tell him I have now a daughter to bestow which he no longer will decline, that this day he still shall be a bridegroom, nor shall a fortune, the merit which his father seeks, be wanting," he promises. When Cimberton discovers that only half of Sealand's dowry is available, he rejects Lucinda, now free to marry Myrtle.

“The tender husband”

Time: 1700s. Place: London, England.

Text at https://archive.org/details/tenderhusbandor00steegoog https://archive.org/details/tenderhusbandora00steeuoft https://archive.org/details/richardsteele00steeuoft https://archive.org/details/britishtheatre20bell

Sir Henry Gubbin agrees to marry his son, Humphry, to a fine heiress, Tipkin’s daughter, Biddy. But Humphry is unwilling, all the more because the two are cousins, and Biddy is also unwilling, considering him no more than a country booby. Also unwilling that this marriage plan succeed is Captain Clerimont, who promises Pounce, the family lawyer, one thousand pounds to favor Biddy’s marriage to his younger brother, a lazy retired captain eager to marry wealth. Pounce introduces Clerimont to Biddy and her aunt, Barsheba. While the aunt mistakenly thinks that Pounce is courting her, the captain succeeds in flattering Biddy’s taste for romance with choice phrases. Clerimont’s mistress and spy to his wife’s extravagant spending, Fainlove, disguised as a man, promises to introduce a sister, in truth her own person, to a Humphry eager to counteract his detested father. When Humphry meets Biddy, she sneers at the apparent “wild man”. “What wood were you taken in?” she sarcastically asks. “How long have you been caught?” Yet she likes the “ungentle forester” much better after he reveals his intention of finding a reason to rid themselves of each other. The occasion is propitious, for Barsheba presents a painter for the prospective bride’s portrait, the disguised captain, whom Biddy recognizes by his voice. When the aunt leaves the room a moment, Humphry obliges by doing the same and so favors the budding romance as well as providing a coach so that the couple may elope. Meanwhile, Fainlove hands over to Clerimont a compromising letter written to herself from his wife. To trap his wife, Clerimont bursts inside her chamber with a drawn sword, pretending to challenge Fainlove while the latter draws hers. When Mrs Clerimont defends Fainlove, Clerimont shows her letter, at sight of which she swoons. The tender husband then praises her servant, Jenny, for her part in obtaining the letter, which prompts Mrs Clerimont to chase her away and promise to amend. To belittle his father, Humphry presents Fainlove as his wife, at which he beats and chases them out of the room but is then reconciled to the couple after being told she has money.

Susanna Centlivre

Irish-born Susanna Centlivre (1670-1723) reached her peak with "A bold stroke for a wife" (1718).

“Alone of Centlivre‘s plays, it has no subplot. Yet it has as much variety as any. [Fainwell fools a traveler, a steward antiquarian, a merchant, and a Quaker, the first two conservative Tory-types, the other two Whig types]...Sir Philip and Prim represent opposite extremes of the moral and social spectrums. Sir Philip is a beau and libertine, but there is a hint that his professed libertinism is only a show. Prim's rigid morality, by contrast, conceals his lasciviousness...Periwinkle is...a credulous student of natural history...Centlivre draws a contrast between [Tradelove, a stockjobber, seen as a social parasite] and Freeman, a genuine merchant [seen as a social provider]...Because of the repeated use of the same device, Centlivre had to be especially careful to prevent the repetition becoming too apparent. The problem is partly solved by the very different characters of the guardians...But Centlivre also made each successive guardian more difficult to outwit and varied the pace and structure of each act” (Lock, 1979 pp 108-114). "Fainwell is charged with the difficult task of swindling four divergent guardians out of their signatures in order to complete a marriage contract that would win the hand, and riches, of the fashionable Anne Lovely...[The play] offers an important alternative model for marital relations, one in which male and female parties are not contract negotiators subject to legally inscribed gender hierarchies, but enthusiastic costars on a shared stage of possibility" (Davis, 2011 pp 520-521).

Relative to the period, Lock (1979) ranked Centlivre’s overall achievement equal to Crowne and Behn, below Farquhar and Steele. “At her best...she wrote amusing and lighthearted comedy of considerable distinction” (p 134).

"A bold stroke for a wife"

%3B_A_Bold_Stroke_for_a_Wife.png)

Time: 1710s. Place: London, England.

Text at https://archive.org/details/britishdramaaco03unkngoog

Colonel Feignwell loves Anne Lovely, whose father left her 30,000 pounds in the charge of four guardians, to spend three months of the year with each. Anne chafes at the Quaker dress imposed on her by Obadiah Prim and his wife, Sarah. Anne wants to marry the colonel but without relinquishing the 30,000 pounds, so that Feignwell must somehow please all four. He meets Philip Modelove, the "beau guardian", in a public park, and, to please his taste, feigns to be a fashionable gentleman of French extraction steeped in French manners. Modelove is impressed to the extent of promising him access to Anne, at present under the charge of the Prims. But when Modelove presents his candidate to Anne, she does not recognize her lover in his unfamiliar clothes. "Heaven preserve me from the formal and the fantasic fool," she prays. When he tries to slip her a letter of explanation, it drops and is discovered by Prim, but, on recognizing Feignwell, she quickly takes it and tears it up in pretended anger. "Thy garb savoreth too much of the vanity of the age for my approbation," Prim announces to Feignwell. The two other guardians arrive on Modelove's summons: Tradelove and Periwinkle, the first a broker addicted to trade and the second a gentleman addicted to antiquities, neither of whom liking Feignwell in his present disguise. In no way discouraged, Feignwell next dons an antique disguise to please Periwinkle's taste, pretending to possess ancient objects of all kinds, including a bottle carrying "part of those waves which bore Cleopatra's vessel when she sailed to meet Mark Antony" and a belt that carries the bearer across the world and makes him invisible. When Periwinkle puts it on, he and the landlord helping in the plot pretend he truly is invisible. Feignwell next dons the belt and drops through a trap-door when Periwinkle's back is turned while continuing to speak with him. He specifies that a sage in Cairo told him that he would benefit humankind by yielding the belt to the first man he met among four in charge of a woman. However, the cheat is discovered when a tailor walks in and speaks out Feignwell's name. To console him, his friend, Freeman, devises a second plot. Freeman tells Periwinkle his uncle is dying, a lie to make him believe he is near to becoming his heir. Meanwhile, disguised a Dutch merchant, Feignwell encounters Tradelove who has been told by Freeman false information on the raising of a siege by the Spaniards. Based on this knowledge, Tradelove recklessly buys expensive stock and bets with the supposed merchant that the news is true. When the news is discovered to be false, Freeman pretends to Tradelove to have lost his money, too. Freeman proposes that the merchant may be willing to forget the debt if Tradelove consents to have his ward marry him. Feignwell next disguises himself as the steward of Periwinkle's supposedly dead uncle, showing him a forged document in which he is named the heir, with a request to renew the steward's lease on a farm. Periwinkle signs his agreement. Having three of the four disposed of, Feignwell disguises himself as a Quaker named Simon Pure, and visits the Prims on the recommendation of friends of the sect. He convinces the Prims he has converted Anne to their cause. The youn couple pretend to be inspired by religion so that the Prims readily agree to their marriage. The real Simon Pure arrives too late with witnesses of his true identity to prevent the marriage.

Joseph Addison

Tragedy in the early 18th century is capably represented by Joseph Addison's (1672-1719) "Cato" (1713), based on the life of Cato the Younger (95-46 BC), Stoic philosopher and political opponent of Julius Caesar (100-44 BC).

The major source materials of "Cato" are found in Cicero, Lucan, Sallust, and Seneca. "In Cicero and Seneca he has become an embodiment of the Stoic wise man, and in Seneca, in particular, he becomes also an incarnation of the Roman republic...Lucan goes beyond even Seneca...Cato...is exalted as high, if not higher, than the gods...The proof of Cato's natural virtue comes when he is confronted with the dead body of his son, Marcus...Virtue here means public spirit, and the 'bloody corpse' of Marcus, fresh with the wounds of battle, no longer represents the body politic of Cato's son, but rather the body politic of departing Rome. Since Rome has expired, so too must Cato...He departs this life guided by the lights of reason and nature, following the dictates of that Stoic principle which is only partly Christian, that virtue in itself will make men happy" (Kelsall, 1966 pp 150-159). "Cato's decision to commit suicide is predicated on the assumption that no hope for Roman freedom remains because Caesar is at the gates of Utica, but Gato is not and cannot be certain that all is lost...When Portius, in scene iv, brings news that Pompey's son has sent a ship to Utica promising aid to Cato, Cato's resolve to commit suicide begins to appear mistaken...Cato has ‘done amiss’ in being ‘too hasty’" (Malek, 1973 pp 516-517).

"The drama depicts republican Rome's doomed resistance to Julius Caesar's growing power and Cato's ultimate decision to take his own life rather than to submit to what he sees as the tyrannical rule of Caesar and the suffocation of Roman liberty. Offsetting the political action is a romantic subplot, featuring a romance between Marcia, Cato's daughter, and the Numidian prince Juba, as well as a romantic triangle involving Cato's two sons and the daughter of a Roman senator...‘Cato’ begins by announcing the conflict between love and Cato’s stern virtue in Portius' opening-scene exhortation with his brother...and although the tragedy ends with Cato's suicide in the name of his principles, his final words arrange the marriages of the play...Stoicism emphasizes self-command through the subordination of the passions to reason, in order to achieve a proper degree of detachment and the impartiality which enable an individual to endure misfortune and failure with equanimity. Other aspects of Stoicism include living in harmony with nature, and as part of its commitment to that harmony, a belief in the unity and interdependence of the cardinal virtues of justice, temperance, prudence, and fortitude; and the belief that liberty requires a life committed to these virtues...Cato's ‘soul breathes liberty’ but it is not simply freedom from constraint which Cato appears to endorse- a rational control of passions shapes the passion themselves until the individual desires that which he ought to desire, in the way he ought to desire it. In Cato's words, "A day, an hour of virtuous liberty/Is worth a whole eternity of bondage’...Marcia is depicted as sharing her father’s devotion to Rome, his severity, and his constancy of mind...One of the things that makes Cato's story a tragedy is that his patrotism, love of liberty, and willingness to defy the superior force of Caesar...make his suicide inevitable...While Cato’s refusal to negotiate with Caesar is indicative of his admirable attachment to Roman liberty, the manner in which he rejects Caesar's overtures is high handed, ungracious- even churlish- and certainly impolitic, if not suicidal...Clearly disgusted with the erosion of Roman virtue which has permitted Caesar's rise, Cato prefers the extreme course of washing his hands of this Rome rather than taking the more moderate, Ciceronian course of trying to work from within either to rehabilitate it or to temper the effects of Caesar’s rule...Upon learning that Marcus has fallen during combat with Caesar's forces, Cato's first response is to express satisfaction of the manner of Marcus's death and to thank the gods that Marcus did not shirk his duty of defending Roman liberty...Addison underlines Cato’s preference for the public over the private..in which Cato chides his fellow Romans for mourning Marcus...The Stoic virtues may be laudable, but they cannot be the essential virtues, as they do not take into account our social and political natures...In Epistle XI, Seneca exhorts Lucilius to ‘cherish some man of high character and keep him ever before your eyes...Choose therefore a Cato.’ Addison clearly...admires certain facets of Cato's character but the play and the spectator call into question the notion that the dramatic Cato is a model simply to be imitated" (Henderson and Yellin, 2014 pp 223-241).

Some critics were quick to downgrade "Cato" relative to the severe criteria of Shakespeare's Roman plays. According to Downer (1950), “the language of the play is cold, elegant, and florid. Each act ends with a passion and a simile” (p 263). Likewise Nettleton (1914): "a conspicuous triumph for classical drama was won in 'Cato'...an appeal to the reason. Cato and his companions, like Plato, reason well. But they remain abstractions of thought, rather than living personalities. Cato has the chill of a statue, a Galatea without the touch of life that permits descent from the pedestal...The classicists had, indeed, scant reason for complaint. The action takes place in 'a large hall in the governor's palace of Utica', the time is confined to 'the great, the important day; big with the fate of Cato and of Rome'. And the interest centres in Cato. Death occurs off the stage in the case of Marcus, while it is again off the stage that Cato runs on his sword, though he is brought in dying. There are feeble attempts at local colour, but Addison's Numidian touches suggest no more than Dryden's faint Spanish and Oriental settings. Everywhere the chill of death seems to rest. The characters are benumbed in action and constrained in expression. Even the passages that are commonplaces of quotation suffer from want of vital feeling" (pp 179-182).

"Cato"

Time: 1st century BC. Place: Utica, Italy.

Text at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cato,_a_Tragedy http://www.constitution.org/addison/cato_play.htm https://archive.org/details/britishdramaaco03unkngoog http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/31592

After defeating Pompey's army at Pharsalia, Julius Caesar arrives in Rome as a conqueror, but finds resistance in Cato the Younger, who recommends to Caesar's messenger as follows. "Bid him disband his legions,/Restore the commonwealth to liberty,/Submit his actions to the public censure,/And stand the judgment of a Roman senate." The Numidian prince, Juba, once conquered by Caesar, proposes to Cato to arm Numidia in defense of the Roman senate. "And canst thou think/Cato will fly before the sword of Caesar?" he responds. Hoping to obtain from Caesar the hand of Cato's daughter, Marcia, in marriage, Sempronius encourages his troops to rebel against Cato, fortified by Syphax' Numidian troops. Meanwhile, Cato's sons, Marcus and Portius, are rivals for the same woman, Lucia. Unconscious of his brother's sentiments, Marcus asks him to speak to her on his behalf, but Lucia's choice is Portius, though she proposes to postpone progress of their relation while "a cloud of mischief" hangs over them all, to which Portius grievingly submits. Sempronius' rebellion is turned away by the mere presence of Cato confronting the rebels. Disguised in Juba's dress, the angry Sempronius gains access to Marcia's chambers in the hope of carrying her away, but is surprised and killed by Juba. Marcia enters grieving for what she thinks is the fallen Juba, overheard by him, thinking first she is speaking of Sempronius, until to his joy he hears her say: "Marcia's whole soul was full of love and Juba." In defense of Rome against Numidian troops, Marcus blocks Syphax' path, but both are killed in battle. Cato admires his son's death. "Welcome, my son!" he exclaims. "Here lay him down, my friends,/Full in my sight, that I may view at leisure/The bloody corpse, and count those glorious wounds." Yet Caesar's march is inexorable. In despair, Cato falls on his sword after recommending Juba to Marcia, Portius to Lucia. In grief over the loss of his father and his country's woes, Portius concludes thus: "From hence, let fierce contending nations know/What dire effects from civil discord flow:/'Tis this that shakes our country with alarms/And gives up Rome a prey to Roman arms,/Produces fraud, and cruelty, and strife,/And robs the guilty world of Cato's life."