A harmonic interval consists of two notes played at the same time or consecutively. The distance between the two notes is called an interval.

A predominant type of harmonic interval known as the power chord consists of the root note of the chord and a fifth. An advantage to understanding power chords is their shape can be used to quickly determine the location of perfect intervals. This improves ones overall understanding of the location of notes on the fingerboard by relation to one another and builds the groundwork for understanding scales.

A chord is named after its root note, which is typically the lowest note. E.g. a C chord consists of the notes C E G, with C most likely to be the lowest note. Chords may be modified by "inverting" them, which means to reorder the pitch of the notes by raising or lowering them an octave, e.g. playing a C chord as E G C, which would be named C\E. However, the general rule of thumb among guitarists is to refer to a chord by its lowest note. For details on variations, please see the chords section.

A basic understanding of tablature is essential for understanding this, and most other sections of this book.

Power Chords

Perfect fifths (e.g., C-G) and their inversion, perfect fourths (e.g., G-C), are the most consonant interval on the guitar (and in all of music for that matter), not counting unison and octaves. For this reason, playing a perfect fifth or fourth is often called a power chord.

It is more difficult to play the octave for a root note on the D string, because the B string is tuned differently than the other strings, and you will need to stretch further to reach the octave. Power chords are most commonly played on the thicker strings, and many songs exclusively use perfect fifth power chords.

Perfect Fifths

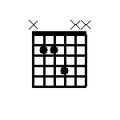

The simplest perfect fifth power chord uses the same fingering as an E minor chord, except only the thickest three strings are played. Here is the fretting for the E5 power chord:

.png) E5 Power Chord

E5 Power Chord

When you play a power chord in the open position (or any power chord), you have to be careful to mute the other strings so they do not ring out. In this case, if you also played the G string, you would be playing a full chord, not a power chord. Use your extra fingers to lightly touch the other strings, use your fretting fingers to smother the unnecessary strings, or just avoid hitting the unnecessary strings with your impact hand.

Power chords, and really any chord types, are useful because they can be moved anywhere on the neck, as long as the relationship between the notes is the same. For example, in the E5, the thickest string plays an E, the next string plays a B (which is the fifth note of any E scale), and the next string plays another E, but an octave above it.

If you take the same chord pattern, and move it up the neck to make a different power chord. For example, take the two fretted notes, then use your first finger and fret the thick E string two frets behind the others. For example, if you were fretting the E string at the third fret, you would be playing a G5 which looks like this:

.png) G5 Power Chord

G5 Power Chord

There are several different fingerings you can use to play a power chord, but it is best to choose one that lets you easily move the power chord up and down the neck.

Here are three most common fingerings for a power chord, in this case, a G5. In the second and third fingering, the two strings are barred at the fifth fret. The numbers indicate the number of finger to use. Finger #1 is the index finger, #2 the middle finger, #3 the ring finger, and finger #4 is the little finger.

EADGBE EADGBE EADGBE ---xxx ---xxx ---xxx 1 ...... 1 ...... 1 ...... 2 ...... 2 ...... 2 ...... 3 1..... 3 1..... 3 1..... 4 ...... 4 ...... 4 ...... 5 .34... 5 .33... 5 .44...

Alternate Fingerings

One common variation on the power chord involved omitting the second, higher octave note. For example, a G5 without the second G would look like this:

.png) G5 Power Chord with the octave omitted

G5 Power Chord with the octave omitted

These are easier to play because you only need two fingers and the sound is similar to the three string version.

Since a power chord is just playing multiple strings that produce only two tones, it is possible to play all six strings and still be playing a power chord. Some open tunings set the guitar up so that when you strum it open, it plays a power chord. Here is an example of a full G5 chord, where all strings are either playing a G or a D.

EADGBE --00-- 1 ...... 2 ...... 3 2...11 4 ...... 5 .4....

This chord can be considered a non-traditional power chord, since in popular music, power chords usually use only two or three strings. This is also a hard fingering for the beginner, but it emphasizes an important fact about double stops: as long as you keep adding octave or unison notes, you will always be playing the same interval. Playing a non-octave or unison note will instead produce a chord.

Adding unison notes may sound different even though they are supposed to produce the same pitch. This may be because the strings have different tension or thickness. In general, the guitar's thinner strings will have a brighter, more ringing sound.

Perfect Fourths

Perfect fourths have a slightly more suspended sound than perfect fifth chords. These are easy to play, because most of the strings on the guitar are tuned in fourths. This means that playing any two of the thickest four strings, when they are beside one another and played at the same fret. For example, a D4 is played like this:

D4 Power Chord with the octave omitted

D4 Power Chord with the octave omitted

EADGBE xx00xx

These can easily be moved up the neck. For example, a G4 or a B4 would be played like this:

G4 Power Chord with the octave omitted

G4 Power Chord with the octave omitted B4 Power Chord with the octave omitted

B4 Power Chord with the octave omitted

EADGBE EADGBE (33xxxx) (x22xxx)

Perfect fourths are the same as the upper two notes of the original three-string power chord. It is rare to add a new top octave, but it may done. The following Power chords show the G4 and B4 with the octave added:

G4 Power Chord with the octave

G4 Power Chord with the octave B4 Power Chord with the octave

B4 Power Chord with the octave

EADGBE EADGBE (335xxx) (x224xx)

Other Double Stops

You can play a huge variety of different intervals by playing chords, and just plucking two notes at the same time. Often you can add variety to chord strumming by playing a quick fill by playing different sections of a chord, and achieving different intervals.